By Matt Davis, The Lens staff writer

No public agency’s budget is a bigger source of intrigue in New Orleans than Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman’s.

The historic lack of openness around the Sheriff Office’s budget is “jaw-dropping,” said Rosanna Cruz, spokeswoman for the Orleans Parish Prison Reform Coalition.

“The sheriff gets money from the state, the city, the feds, and also all these different enterprises from within the jail,” Cruz said. “The prison is a profit-generating machine for the sheriff, and his position is very powerful, and that legacy has been built on the number of people we’ve incarcerated over the last 30 years.”

Gusman has repeatedly denied that he houses inmates to make money, and he has even said recently that he is open to negotiations about how his jail is funded — a leap forward in the relationship between his office and the city that has been historically fraught with legal and personality battles.

Under former Sheriff Charles Foti, budget requests to the city were notoriously vague, as little as one line, showing how many prisoners were likely to be incarcerated over the coming year and the cost to the city for their incarceration.

This year, Gusman’s budget request to the city broke his revenues and expenses into more detail than ever before, showing for the first time the $235,000-a-year that the sheriff makes from a 3 percent bail bonds fee, for example. But the budget still leaves plenty of outstanding questions for those interested in the inner workings of the jail.

One member of the Orleans Parish Prison Reform coalition, a broad coalition reconvened in October after a five-year hiatus, has been scrutinizing budget requests to the city made by the sheriff’s office for decades.

“The lack of detail in the sheriff’s budget request to the New Orleans City Council has been a chronic problem going back to Foti, and continuing for many years,” civil-rights attorney Mary Howell said. “And it’s ironic that this issue continues to arise with Sheriff Gusman, because he was one of those who used to complain about Foti’s budget requests both when he was chief administrative officer and when he was on City Council.”

Gusman’s 2011 budget is $67 million. He asked for $36.3 million from the city, and has been allocated just $22 million in Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s proposed $483 million general fund budget for 2011. For comparison, the biggest city department, the New Orleans Police Department, has asked for $120 million next year.

Despite the relatively smaller budget, critics and some council members say any money saved from the sheriff’s budget could be put to use on other citizen priorities in this particularly tight budget year.

Seeking clarity

The Lens decided to get a clearer picture of Gusman’s finances, filing a public records request for Gusman’s general-ledger accounting detail in July. We wanted to find out how much Gusman spends to run his jail, right down to how much it costs to cut keys for the antiquated cells in his aging facilities, buy uniforms for his deputies, and buy feed for his on-site tilapia farm.

Gusman’s attorneys are still holding back that detailed accounting information, pending redaction of 7,500 pages to protect the privacy of Gusman’s employees under state public-records law. When the information is turned over, The Lens will publish it.

In the meantime, here’s what we can tell about how Gusman spends your tax money by probing his budgets from 2009, 2010, and his proposed budget for 2011. The source of this information is Gusman’s own submissions about his budgets to the State Bond Commission, for 2009 and 2010, and to the City Council in 2011.

An expensive business

Gusman’s staff of over 1,000 non-union sheriff’s deputies start on just $9-an-hour, leading to recruitment and retention problems, he told council members when presenting his 2011 budget request earlier this month. That budget request included a 5 percent raise for many of those staffers.

According to his 2011 request, Gusman will spend $21.7 million next year on deputies to provide security at his various facilities, including:

- * $4.7 million to secure the 831-bed Orleans Parish Prison,

- * $4.1 million to secure the 841-bed House of Detention,

- * $1.6 million to secure the 288-bed women’s jail on South White Street, and

- * $2.3 million to secure the 704-bed temporary detention tents built after Hurricane Katrina.

- * $2.4 million to secure the 408-bed Conchetta facility, a former motel off Tulane Avenue.

- * $1.8 million to secure the Templeman V facility, which houses 316 federal prisoners.

Gusman spends $11 million a year on central services such as his legal department, administrative support, internal affairs and risk management. It costs $7 million a year to run Gusman’s kitchen, and $6.3 million a year to maintain his decrepit jails.

Gusman’s tilapia farm is relatively self-sustaining, it seems, requiring just $7,000 in the 2011 budget.

Opaque lump-sum expenses

Gusman’s 2011 budget also includes some significant lump sum expenses with very little explanation. Gusman’s spokesman, Malcolm Ehrhardt, has not answered questions about each of these items.

For instance, Gusman’s budget contains a line item of $545,000 for communications, including nine employees. Ehrhardt recently told The Lens his company is contracted at a rate of $2,500-a-month to do Gusman’s public-relations work, so it’s not clear what the extra budget is paying for — perhaps for radio systems.

Gusman’s administrative office itself has just five employees, but he requested $7.2 million for its operation next year, with no detail.

Gusman also projects paying $4.2 million to provide security inside the Criminal District Court in 2011, but he provides no breakdown.

The budget includes $1.3 million for “grants and special programs,” setting aside $150,000 for “special projects,” but it’s not clear what that represents.

State, city, and federal inmate revenues

Gusman has increasingly relied on revenues from the state to fund his operations over the past three years, and his jail holds more state prisoners than any other parish facility in Louisiana.

Gusman has a mix of facilities — jails for those awaiting trial, and a prison for those who have been convicted.

The state pays $26.39 per inmate per day for Gusman to house its inmates convicted on state charges. The city pays $22.39 per inmate per day for Gusman to house inmates arrested by the New Orleans Police Department, as well as medical costs and court services. The U.S. Marshal’s office pays $43 per federal inmate per day, or $45 per inmate per day for an immigration inmate.

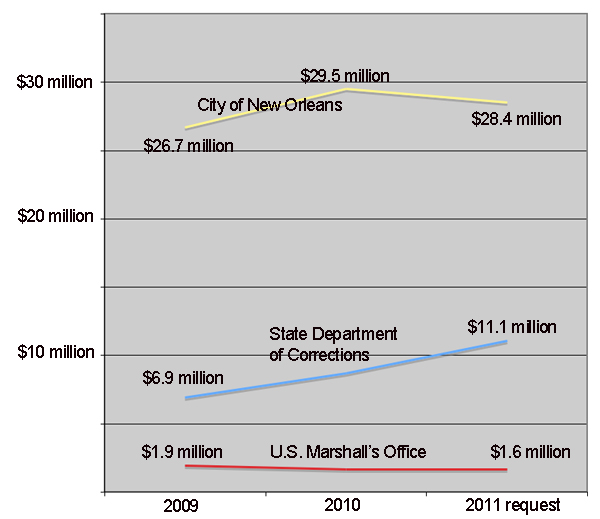

Gusman’s state revenue has risen by over 60 percent over three years from $6.9 million in 2009 to $11.1 million predicted in 2011. Meanwhile, Gusman’s revenue from the city and the U.S. Marshal’s office is actually expected to be down in 2011 compared to 2010.

Before Hurricane Katrina, Foti and Gusman housed more than 3,000 state inmates at the jail, among a population of 7,500 inmates. Recent assessments by an independent consultant working with the National Institute of Justice show Gusman is housing around 950 these days, among a population of around 3,200.

Gusman applies to the U.S. Marshal’s office to house federal prisoners, with the final decision made by the marshal’s office.

But The Lens got two different explanations about who decides how many state prisoners are housed locally.

That’s “the state’s call,” Gusman said in a September interview.

But the state said it’s up to Gusman, and that he can keep as many state prisoners as he has room for. The main reason Gusman is earning more money for housing state prisoners lately is because he has more room for them, said Pam Laborde, spokeswoman for the Louisiana Department of Corrections.

“In terms of approval of offenders, the Department does not send offenders to OPP [Orleans Parish Prison],” Laborde wrote in an e-mail. “Generally, the sheriff will just keep offenders from Orleans Parish who have been sentenced to DOC custody in the facility if there is room available so long as it does not exceed the approved Fire Marshal capacity.”

Gusman has applied to raise the capacity of his jail to hold state prisoners repeatedly since Hurricane Katrina. His jail is audited against the state’s basic jail guidelines, with audits in 2009 and 2010 both noting that there is “room for improvement” in living conditions, but approving Gusman’s requests to expand state inmate capacity.

Though Gusman is holding the largest number of state prisoners, he’s below the state average if such inmates are measured a percentage of all inmates. The average percentage of state inmates in parish prisons is 44 percent; Gusman was holding 29 percent during a recent one-day snapshot, on Oct. 29.

If Gusman has more state inmates than he has room for, those offenders are taken on a weekly basis to Elayn Hunt Correctional Center in St.Gabriel, Laborde said.

Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s Criminal Justice Working Group has been considering placing a cap on the number of state inmates as part of its deliberations over Gusman’s rebuilding plans. After all, if no action is taken regarding state prisoners, any policy change to reduce city inmates will only free up more space for the state prisoners, who are attractive to Gusman because of the higher daily rate paid by the state.

The Orleans Parish Law Enforcement District

Gusman also gets money for jail construction and upkeep from the Orleans Parish Law Enforcement District, a bond-issuing entity, which also finances other city law-enforcement entities such as Criminal District Court. Gusman is the chief executive of the district, and the City Council serves as its board.

Since 2000, the sheriff’s office has received bonding authority for just over $54 million for jail construction and upkeep from the district. Gusman’s records show he’s spent about $17 million of those bonds through the end of 2009.

These bonds are repaid by a voter-approved citywide property tax of 2.9 mills, out of the total city millage of 139.84 mills, or 2 percent of property taxes.

FEMA money

Federal Emergency Management Agency records show Gusman is slated to receive a total of $213 million for the reconstruction of his facilities in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina.

Gusman has said that FEMA will pay all the costs of building a new jail, but not everyone is willing to take him at his word.

ACLU of Louisiana Director Marjorie Esman filed a public-records request with Gusman in early November, telling reporters that Gusman “has never disclosed the extent of FEMA funds or the conditions imposed upon those funds.

“The public still has no idea where the hundreds of millions of dollars needed to expand the prison is coming from,” Esman said.

FEMA will only pay out Gusman’s claims once the work is complete, said a FEMA spokesman, and those decisions will be made on a case-by-case basis.

Confusing revenue sources

Several other lines in Gusman’s 2011 budget warrant closer scrutiny. We asked Gusman’s spokesman to clarify questions about each of these items on Nov. 10, but he has not answered.

For the past three years, Gusman has reported millions of dollars in “other revenue” in his budgets, from $3.8 million in 2009, to $4.5 million in 2010, to just $500,000 in 2011.

Gusman told the council on Nov. 9 that the 2011 “other revenue” is a combination of fees collected for off-duty details, interest income, and the $60-a-month fee for take-home cars that some deputies pay. It’s not clear whether that was also the case in 2009 and 2010, or where the interest is coming from.

Then there’s Gusman’s recent move into the sale of blighted and foreclosed properties, as well as seized vehicles.

In January 2010, the civil and criminal sheriff’s offices merged under Gusman.

Previously, former Civil Sheriff Paul Valteau’s office took 3 percent of the value of houses sold and 6 percent of cars.

Now, according to Gusman’s website, his office gets that money, on top of the fees for services such as evictions, executing writs and court orders.

Analysis of house sales information available on Gusman’s website shows that house and vehicle sales between January and October 2010 total just over $2.5 million in revenue for the sheriff.

No revenue line for these sales was included in Gusman’s 2011 budget.

The city is also moving to sheriff’s sales as part of Landrieu’s new blight-reduction strategy, projecting five properties a week in 2011 at a charge of $600 per property for Gusman, but that expected revenue wasn’t included in Gusman’s 2011 budget, either.

Gusman also seems to be making a profit from providing telephone services to his inmates. His 2011 budget includes a revenue line of $1.94 million for “inmate telephone.”

Gusman also expects to earn $1.35 million in 2011 from “work release fees,” suggesting he is making a profit from farming out his inmates to work in the community.

Gusman’s budget also includes $722,000 in revenue from “out of parish inmates,” but it’s unclear how this arrangement is structured because the city pays for Gusman to hold inmates arrested on warrants from Jefferson and St. Bernard parishes.

Landrieu’s working group has considered reducing the number of inmates held on out-of-parish warrants under new policies proposed by New Orleans Police Department Superintendent Ronal Serpas.

Facing bankruptcy, or a sound credit risk?

Gusman has given varying accounts of his agency’s financial position over recent months.

For example, Gusman wrote that without more money from the city, his office could be forced to declare bankruptcy or cease operations in a letter to Landrieu on July 29 as part of his 2011 budget application.

Gusman’s 2011 budget prediction shows his office will end the year $14 million in the red:

Gusman is required to balance his budget under state law, so it’s unclear how his office is able to run a deficit.

For the past three years, the sheriff’s office has also reported an “estimated beginning fund balance,” of $4.4 million in 2009, $946,000 in 2010, and negative $2.5 million in 2011.

Councilwoman Susan Guidry asked Gusman at a budget hearing on Nov.9 whether Gusman keeps a “reserve fund.” Gusman said he didn’t.

We asked Ehrhardt, Gusman’s spokesman, for a breakdown of the “fund balance” on Nov. 10. Ehrhardt did not answer our questions.

Meanwhile, in March, Gusman felt his office’s financial position was stable enough to apply to the State Bond Commission for a second $6 million loan to cover operating expenses. Gusman had applied for, and paid back, a similar loan in 2009, according to the commission.

The commission voted to give Gusman the loan, over the concerns of an in-house analyst.

“Basically the concern is continuous deficit of operation for past three years,” analyst Cindy Chen wrote in an e-mail to the commission.

House Speaker Jim Tucker, R-Algiers, chairman of the bond commission, said he recommended approval of the loan over the analyst’s concerns because many Louisiana sheriffs have budget deficits while they wait on FEMA reimbursement following Hurricane Katrina. Gusman, too, said his office is unlikely to face a problem repaying the money to the commission this time around.

“We’re going to pay the loan off,” Gusman told The Lens and Fox8 News in October. “That’s not an issue.”

Credit analysts seem to think Gusman remains a safe bet, too. The Orleans Parish Law Enforcement District is rated AAA by the bond ratings agency Standard & Poor’s, although the analysts listed on the agency’s most recent report did not respond to questions about whether Gusman’s bankruptcy predictions could affect that bond rating.

In Europe, the Irish government also had a AAA bond rating by Standard & Poor’s until 2009, when the agency downgraded its rating over fears about the state of the country’s finances. This weekend, the European Union had to make a multi-billion effort to bail-out the Irish.

Apparent lack of council interest or concern

Civil-rights attorney Howell sees a direct link between a continued lack of clarity around the sheriff’s budget and poor conditions at the jail, saying the city has historically gone along with vague budget requests from the sheriff’s office in exchange for washing its hands of the city’s statutory obligations to furnish a jail.

“It’s not just a question of what’s going on in the budget. The city needs to be more interested in what’s going on in the jail. Is it safe? Is it humane?” Howell said. “I think that unfortunately, the city’s attitude has been that we’ve hired the sheriff to do this, and he can do whatever he thinks is best. So there’s been very little oversight of the quality of what the city is getting for what it’s paying.”

The council’s Budget Committee Chairman, Arnie Fielkow, passed inquiries about Gusman’s budget onto the co-chairwomen of the council’s Criminal Justice Committee, Susan Guidry and Jackie Clarkson.

Guidry and Clarkson declined comment on this story.

Landrieu’s office also declined comment.