Stunning new data not yet publicly released shows Louisiana losing its battle with rising seas much more quickly than even the most pessimistic studies have predicted to date.

While state officials continue to argue over restoration projects to save the state’s sinking, crumbling coast, top researchers at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration have concluded that Louisiana is in line for the highest rate of sea-level rise “on the planet.” * Indeed, the water is rising so fast that some coastal restoration projects could be obsolete before they are completed, the officials said.

NOAA’s Tim Osborn,** an 18-year veteran of Louisiana coastal surveys, and Steve Gill, senior scientist at the agency’s Center for Operational Oceanographic Products and Services, spelled out the grim reality in interviews with The Lens. When new data on the rate of coastal subsidence is married with updated projections of sea-level rise, the southeast corner of Louisiana looks likely to be under at least 4.3 feet of gulf water by the end of the century.

That rate could swamp projects in the state’s current coastal Master Plan, which incorporated worst-case scenarios for relative sea-level rise calculated two years ago— which the new figures now make out-of-date. (The state’s estimates of sea-level rise and subsidence are listed on page 83 of the Master Plan.)

The state plan, while “valuable and thoughtful,” has a major flaw, Osborn said.

“The problem is it’s a master plan for the restoration and conservation of a landscape that is moving downward at a faster rate than we realized when the plan was constructed—a rate faster than any place else we are seeing in the world for such a large land area,” said Osborn, who will be a speaker Saturday at Tulane University’s Summit on Environmental Law and Policy.

“With all due respect,” he said, “they have projects designed to last 50 years at one level of relative sea-level rise, when they should be building projects that can function for several generations as sea level rises twice as high, if not higher.”

When new data on the rate of coastal subsidence is married with updated projections of sea-level rise, the southeast corner of Louisiana looks likely to be under at least 4.3 feet of gulf water by the end of the century.

Garret Graves, head of the state Coastal Planning and Protection Authority, did not respond to a request for comment. But in an earlier interview he said the uncertainty of future rates of sea-level rise was one of the biggest challenges facing the plan. The planners, he said, typically have incorporated the then-current “worst case” scenarios for sea-level rise at those locations.

Graves also pointed out that the plan was structured to adapt to changing circumstances. The Coastal Planning and Protection Authority must submit an updated plan to the state Legislature for approval every five years.

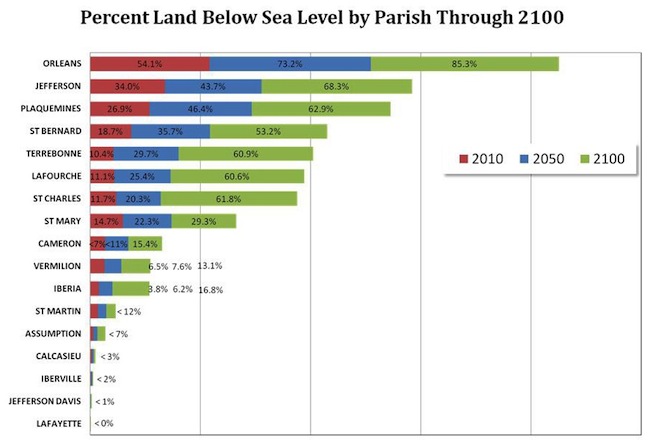

Yet NOAA’s new figures, contained in draft reports currently under peer review, will present a challenge because the numbers have changed so drastically. Even heavily populated areas, such as New Orleans, appear to be sinking faster than expected, in fact even faster than some areas along the coast.

More precise tools show coast sinking faster than expected

Southeast Louisiana—with an average elevation just three feet above sea level—has long been considered one of the landscapes most threatened by global warming. That’s because the delta it’s built on – starved of river sediment and sliced by canals — is sinking at the same time that oceans are rising. The combination of those two forces is called relative sea-level rise, and its impact can be dramatic.

For example, tide-gauge measurements at Grand Isle, about 50 miles south of New Orleans, have shown an average annual sea-level rise over the past few decades of 9.24 millimeters (about one-third of an inch) while those at Key West, which has very little subsidence, read only 2.24 millimeters.

For decades coastal planners used that Grand Isle gauge as the benchmark for the worst case of local sea-level rise because it was one of the highest in the world. But as surveying crews began using more advanced instruments, they made a troubling discovery.

Readings at a distance inland were even worse than at Grand Isle. “For example,” Osborn said, “we have rates of 11.2 millimeters along the south shore of Lake Pontchartrain—the metro New Orleans area. And inside the city we have places with almost [a half-inch] per year.

“So when we looked at the averages we were getting inside the coast, we realized the current figure we should be using for [southeastern] Louisiana is 11.2 millimeters.”

The news got only more bleak when NOAA began using the new technologies to update past rates of local subsidence and then fed those numbers into studies projecting future rates.

“What we see is that the [southeast] Louisiana coast averaged three feet of relative sea-level rise the last century,” said NOAA’s Steve Gill.

Prepare for ‘at least four feet’ of sea-level rise

The draft report of the quadrennial National Climate Assessment, finished by federal agencies in December, showed a steady increase in sea-level rise through the end of the century. Gill said the increase was due to the continued increase in the two main contributors: thermal expansion of marine water volumes as oceans continue to warm, and an increase in the melting of land-based ice, such as glaciers and ice fields. That water eventually makes its way into the ocean, further increasing its volume.

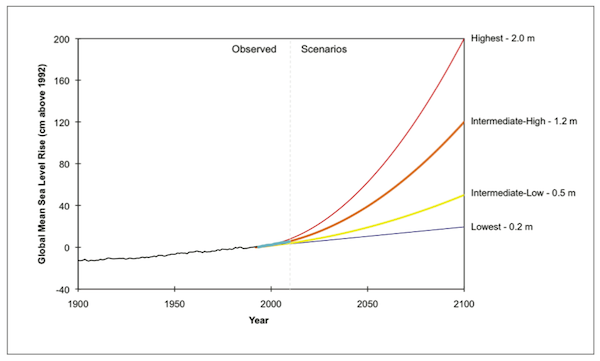

The assessment provides four scenarios for global average sea-level rise through the end of the century, based on varying scenarios of warming and ice melt:

- The first shows current trends holding steady, resulting in about an eight-inch rise globally.

- The second, or intermediate increase, results in about 15 inches globally.

- The third, or mid-range, shows about 4.5 feet.

- The fourth, or worst case, shows about 6.5 feet globally.

The NOAA researchers said they use the mid-range scenario in making local projections.

“Based on the frequency of storms over the last century, we know we can expect 30 to 40 hurricanes or tropical storms to hit this area by the end of this century. Think of Isaac—not of Katrina—and add up the cost of that kind of destruction 30 or 40 times.”

Southeast Louisiana fares much worse in all four scenarios because “we now know the entire area is sinking faster than any coastal landscape its size on the planet,” Osborn said.

“When you combine those two factors, update the rates from what we’ve found with the most recent data—and that is data, not computer models or theories—then you see this area, southeast Louisiana, will experience the highest rate of sea-level rise anywhere on the planet by the end of the century,” Osborn said.

“We’re talking probably at least four feet if not five feet in some sections of this coast. That’s what people here need to be planning for.”

Osborn said he believes coastal Louisiana has a chance at survival because the Mississippi River carries the raw building material—sediment—in such huge quantities that projects could help some areas keep pace with the rising Gulf. But he stressed that the new figures mean current plans need to be amended to focus on the most vulnerable areas, and work must start soon.

“Our goal is to provide meaningful numbers that local planners can use as targets for what they need to prepare for and adapt to,” he said. “And what these numbers tell us is that we need to be planning for the reality that by the end of this century most of this coast will be converted to open water.

“What that tells us, in turn, is what we’ve already seen recently with [Hurricane] Isaac: Even a small storm will result in catastrophic flooding, and not just for people and businesses and infrastructure close to the coast.

“Based on the frequency of storms over the last century, we know we can expect 30 to 40 hurricanes or tropical storms to hit this area by the end of this century. Think of Isaac—not of Katrina—and add up the cost of that kind of destruction 30 or 40 times.

“During Isaac, Louisiana [Highway] 1 to Grand isle was almost impassable. It will be impassable in a few decades unless something is done. Look at what happened to Plaquemines Parish from Category 1 Isaac. More and worse will happen in the next few decades.”

Osborn stressed the new figures mean the state’s Master Plan should be adjusted to meet the larger, faster-approaching threat.

“People are already questioning the wisdom of spending huge sums to protect Louisiana,” he said. “The state needs to make sure they’re proposing plans that will last more than a few decades, that they aren’t asking for billions to build things that might be ineffective before they are even finished being built.”

*Correction: The original version of this story misstated the name of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

**Osborn’s name was misspelled in the original version of this story.