The head of the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority has long said his agency would recommend building controversial river sediment diversions only if research showed that possible gains in wetlands and storm protection was greater than any harm caused to the fishing industry.

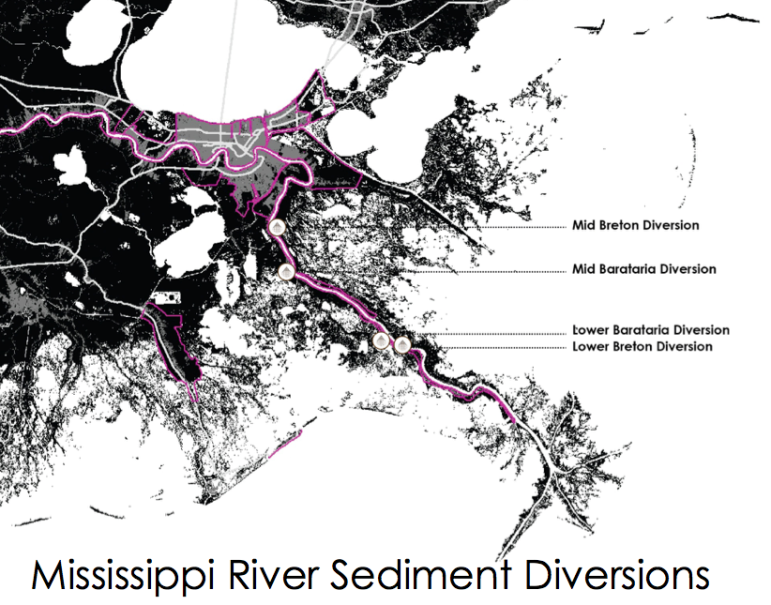

And that was the reasoning Kyle Graham offered Wednesday when announcing his agency supported the Mid-Barataria and Mid-Breton Sound diversions while mothballing the Lower-Breton Sound and Lower Barataria Bay projects.

Graham said modeling showed two other diversions, farther downriver, would not have enough sediment to build land fast enough to offset current rates of subsidence. He said they would be put on hold, but could be reopened to discussion if future research changed projections on river sediment loads.

The agency’s board, appointed by the governor, unanimously approved the recommendations with little discussion.

The Barataria project would run as much as 55,00 cubic feet per second, while Breton Sound would have a ceiling of 35,000 cfs. That is far below maximum flows of over 150,000 cfs that had been discussed in the past.

“This is a pretty big step for us,” Graham said after the vote. “We’re in a place we’ve never been before.”

That doesn’t mean anything will be built soon. Graham said the latest green light for the projects gives his agency the authority to begin final engineering and design, which should take at least two years.

“Then we’ll probably have at least another year dealing with the regulatory requirements – getting all the permits these projects will require,” he said.

But the overflow crowd at the meeting and its steady stream of positive comments indicated this was truly a red-letter day in the state’s race to prevent the Gulf from consuming its crumbling, sinking coastal zone. Some 2,000 square miles of wetlands have been lost in 70 years due to river levees, thousands of miles of canals dredged for oil, gas and shipping, as well as natural geologic faulting. Marshes and swamps that once buffered communities and industries from storm surge and powered one of the world’s greatest fisheries have become open water.

Projections of subsidence and global-warming-driven sea level rise show most of the southeastern portion of the state outside current levees will be under water by 2100 if the state can’t rebuild some of those wetlands over the next 80 years.

A central part of the planning to get that job done has always been using the sediment load carried by the river. That always included river diversions – basically flood gates engineered into the levees adjacent to sinking basins. They would be opened during high river stages to allow the Mississippi’s current to spread the sediment into the embattled marshes.

Opposition cropped up only as the projects neared the end of the planning stage in recent years, and then mostly from some commercial and recreational fishers. They fear the fresh water will force out their target species, such as shrimp, crabs, oysters, speckled trout and redfish. They want the wetlands rebuilt, but only by using pipelines pumping sediment dredged from the river, an option that would not dramatically lower salinity levels.

Studies show the long-term cost of that at method is more expensive than diversions because it must be repeated every few decades, and the costs of operation increase as the pipeline lengthen.

Graham said the latest research and computer models showed there would be little long-term harm to either estuarine species or fishermen. While some species would be displaced and commercial and recreational catches likely would drop during the first years of operation, over the 50-year life of the projects production and catch would return to current levels as lost habitat was rebuilt.

“Overall there were no catastrophic changes in fishing or to the fishing communities,” Graham said.

George Ricks isn’t buying that. A charter boat skipper who heads the opposition group Save Louisiana Coalition, claims the studies were “rigged” because they only evaluated two scenarios: Results with diversions and with no action at all.

“We said from the beginning the only fair study would be one that looked at all options, not just diversions,” he said. “Of course diversions will look better than doing nothing.”

Ricks said economists have said the agency’s socio-economic study on impacts to fishermen was flawed as well. His group intends to bring these issues before the state Legislature – which has twice unanimously approved the agency’s master plans.

“We still have a loot of science from experts to show people,” Ricks said. “I don’t care what they announced today – this isn’t over.”

Graham agreed public comment was far from over. His agency already has scheduled more than 20 public hearings across the state and was receiving requests for more. He was urged by board members to be open to suggestions about operation schemes fishermen might suggest to lower the possible impacts.

“We’ll be listening to people and taking comments for the next few years,” he said. “We welcome the opportunity to explain everything to folks out there, especially those who will be impacted by these projects when they are finally built.”

In other action, the board ended a growing controversy over an plan to use money earmarked for restoration to raise La. 1 to the oil industry hub at Port Fourchon.

Gov. Jindal and Lafourche Parish officials raised the ire of coastal advocates and green groups by asking that any unspent money from RESTORE Act projects be diverted to the La. 1 effort. Critics said that would amount to the state reneging on promises to use all that money on restoring wetlands.

But board chairman Chip Kline announced all sides agreed on a compromise. Turns out the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act, pushed through congress by then-Senator Mary Landrieu specifically to supply offshore oil revenue for coastal restoration, included a very convenient clause: 10 percent of the funding could be used for infrastructure affected by coastal land loss.

Since the flooding on La. 1 is cased by coastal land loss, the project should pass muster, all parties agreed. The board unanimously passed the resolution.