After witnessing the collective outrage over a belated water advisory, I’ve changed my mind. I no longer believe lead-poisoned children should bleed from their eyeballs.

Let me explain.

On Monday the Sewerage and Water Board announced that a brief power outage had caused water pressure to drop at their plant and that the east bank’s water supply might have been compromised. Unfortunately, the incident occurred in the morning but the water advisory wasn’t issued until the afternoon. At that point, it might as well have read, “To ensure your safety, please boil all water before you used or ingested it four hours ago.”

New Orleanians were up in arms over the public health fugazi. Schools were cancelled, restaurants closed. Finally, a full day later, bacteriological tests showed the water was safe all along.

Whew.

Imagine the reaction, though, if some children who consumed water on Monday had become sick. Oh, there would have been hell to pay! There would have been furor. There would have been resignations. Most importantly, there would have been lines around the block at clinics and pediatricians’ offices. Parents would have wanted their kids tested and treated. Everyone would have learned about the harmful effects of coli bacteria.

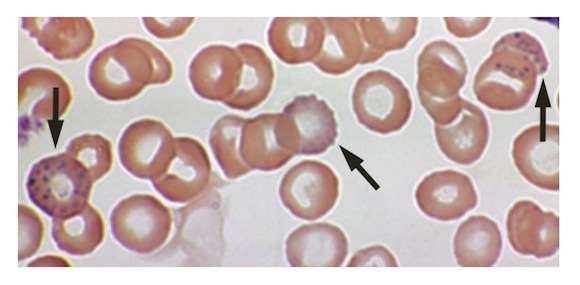

The workers have tried to protect themselves from lead poisoning, but what about neighbors—especially children. photo: Editor B.

Now imagine the same situation, except that water was contaminated by lead. Surely there’d be the same furor, the same urgency to have children tested and treated, and the same desire to learn about the ill-effects of lead … Right?

As someone who has written about the dangers of lead contamination, it almost makes me wonder if a little white lie—on behalf of public health’s greater good— could be justified. “Four hours ago the water supply might have been compromised by lead. Everyone get tested.”

It’s either that or the bleeding eyes idea, because I doubt anything less dramatic will work. In May, New Orleanian writer Thomas Beller unveiled the idea in an essay about his child’s exposure to lead.

Oh, how I wish that every child with elevated lead levels started bleeding out of his or her eyes!

How wonderful! You could go screaming into the streets! You could yell for all to hear that there is blood trickling down their face… Everyone would understand that lead was present in the environment. Everyone would come together to find out where it is. Now! It would be located—in the bare soil where there is no grass, in the playground sandbox, in the walls where paint is chipping—and “remediated.”

Anyone who was doing something like—oh, a random example—sanding the exterior of an old house would know there was a chance that the nearby children would start bleeding from the eyes.

Unfortunately, Beller’s “random” example was not so random. Improper paint removal at a neighbor’s house had dusted the area with lead paint particles, some of which were ingested by Beller’s one-year-old.

Nationally, there was a boomlet of lead news this week.

Matt Yglesias at Slate brought notice to a study by economics professor Jessica Reyes, which links lead abatement in Massachusetts neighborhoods to higher student achievement, even when controlling for community and school characteristics.

Yglesias insightfully summarizes some of the moral dimensions of the issue:

The transmission of social and academic disadvantage through childhood lead exposure is one of the most insidious forms of inequality in the United States. A small child has literally no ability whatsoever to control what kind of water pipes, nearby highways, or building paint he or she is exposed to while growing up. But the disadvantages of early childhood lead exposure—both reduced IQ and diminished impulse control—last throughout life and tend to put one in the very circumstances where you’d end up raising a child who faces heightened lead exposure. And since money spent on removing lead today won’t really pay off for another few decades, politicians are inadequately incentivized to pony up the relatively modest sums of money that could make an enormous long-term difference.

At the Washington Post’s “Wonkblog” Brad Plumer also wrote a post on Reyes’ study. Plumer mentioned the massive payoff of previous investments in lead abatement as well as lead’s potential connection to crime. (That theory is based in part on an earlier study by Reyes):

There’s ample evidence that lead exposure is extremely damaging for young children. Kids with higher lead levels in their blood tend to act more aggressively and perform more poorly in school. Economists have pegged the value of the leaded gasoline phase-out in the billions or even trillions of dollars. Some criminologists have even argued that the crackdown on lead was a major reason why U.S. crime rates plunged so sharply during the 1990s.

Unfortunately, Plumer doesn’t link directly to Reyes paper on the matter. Instead, he links to sociologist James Q. Wilson’s piece on crime published in the Wall Street Journal. In February, I criticized Wilson’s piece and opined that high lead levels might account for New Orleans’ high crime rate.

Granted, Wilson is a respected social scientist and one of the first I’ve seen mention the crime/lead connection in a national forum. My particular beef with the WSJ piece was that Wilson mentioned studies linking reduced lead and reduced crime—and then promptly ignored them. He ended up concluding that the sharp reduction in violent crime over the past 20 years is due to a “a big improvement in culture.”

(Interestingly, Plumer’s Wonkblog entry uses a photo from New Orleans blogger Editor B’s flickr account. A few years ago, Editor B wrote about his daughter’s elevated lead levels and inspired me to study the issue.)

The lead issue has gained momentum on the local front, as well.

Howard Mielke, a professor of environmental toxicology at Tulane University, has done extensive research on the effects of lead contamination—especially in New Orleans. In June, Mielke wrote a letter to the Times Picayune:

Lead contamination of New Orleans is related to the former use of leaded gasoline and dry-sanding of homes. A city ordinance bans power sanding, but painters often ignore it. Post-Katrina the agencies charged with enforcing the ban have been underfunded and ineffective. Because lead exposure is related to violent behavior later in life, perhaps the police should be charged with enforcement of illegal sanding.

I love that last line. I suppose if we can’t have tots sobbing blood, or orchestrated health scares for the greater good, then police tasering of illegal painters atop scaffolding is the next best thing.

In August—some weeks after Beller’s essay and Mielke’s letter—the City Council’s Housing and Human Needs Committee discussed permits for lead paint removal. Council President Stacy Head demonstrated her familiarity with the issue, and said that “lead affects long-term permanent learning disabilities and impulse control.”

Mielke spoke to the council about the dangers of improperly sanding houses and the need for aggressive enforcement. The low point of the meeting occurred when Deputy Mayor Michelle Thomas and Department of Permits and Safety Director Pura Bascos addressed the council. The Lens story on the meeting recounted this depressing testimony:

Thomas told the council that the city has an inspector on duty on weekends to investigate possible illegal paint removal.

However, when City Council President Stacy Head asked how residents could get in touch with that inspector, neither Thomas nor Bascos could provide an answer.

That’s a problem. If no one knows who to call, maybe Mielke’s right about having police enforce the ordinance on safe lead removal. It’s a pretty good interim strategy, at least until the City buys a fleet of “Leadbuster” trucks outfitted with sirens, bullhorns—and perhaps a couple of proton blasters.

The Lens article on the hearings notes an interesting fact about Mielke:

Mielke came to the issue of lead poisoning after his own child was affected, and he’s become one of the nation’s leading academics, studying and documenting the causes and effects of lead poisoning.

Back in May, I met activist Tamara Rubin at the Bayou Boogaloo. She told me that when she found out her child had been poisoned by lead, it inspired her to found the Lead Safe America Foundation. (This week Rubin was quoted in a New York Times story about elevated lead levels in eggs produced on urban farms.)

Rubin also told me about a documentary she was making titled MisLead: America’s Secret Epidemic. The trailer of the documentary heavily features New Orleans, and this month Rubin submitted it to the Sundance film festival.

Rubin gave me a look at some rough footage shot for the documentary. The clips included interviews with local officials and representatives. In an interview Rubin did with Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman, I was very pleased to hear Gusman say, “I know that lead poisoning tends to have a negative effect on brain development and that could certainly have some connection to crime.”

Rubin also interviewed state Sen. J.P. Morrell. Morrell pointed out that lead poisoning is not just an urban issue. Rural areas are at risk, too. For example, aged school buildings in some rural Louisiana parishes might carry more lead risk than old New Orleans school buildings. He says:

Most of the urban areas throughout the state, you typically do a renovation or an upgrade of a school every decade or so. You have schools in the rural part of the state that have never had any substantial work done to them at all. And those are the school sites that they really don’t want parents to have the information as to whether or not they’ve done any substantial remediation whatsoever because most of the time they haven’t. It’s the same school that’s been there for fifty years; exactly the same school.

So what’s the bottom line, you ask?

It’s pretty simple. Lead’s bad—especially for children. And, unlike a potential bacteria surge in the water supply, lead’s already in a lot of our homes and on our lawns. For many of us, it’s present in the bloodstream too, though only a scant few New Orleanians get tested.

We know lead hinders cognitive development and impulse control. Recent studies also link lead reduction to drops in crime and improved test scores.

Currently, there seems to be a growing national and local awareness about lead’s wide-ranging impacts. It’s heartening to see that Head, Morrell, Gusman and other officials are familiar with the issue. However, there still doesn’t seem to be an adequate sense of urgency among our elected officials about this real and present (not potential!) danger. They should take the lead on lead. They should get the lead out! (Pun intended.)

Sure, investments in lead testing, abatement and enforcement will seem expensive in terms of initial cost. But can you name any other single investment that positively impacts our city’s health, safety and education on a permanent basis? Lead removal and abatement must become a top priority for New Orleans. The payoff is exponential, whereas the cost of poisoning another generation of kids is indefensible.

Beller, Mielke, Editor B. and Rubin were stirred to action by their child’s exposure to lead. They have written essays, formed foundations, done scientific research, created projects, made documentaries…. all to raise awareness and help solve the lead problem, which is especially severe in New Orleans.

What will it take to get the rest of us to act? What needs to happen before we get as outraged about lead in our kids’ blood as we got this week over (possible) bacteria in the water supply? Do kids need to get poisoned? Do they need to bleed out their eyes before we tackle this problem together? .

I know we can do it. If we can come together to inform ourselves and take action on a slow-motion mega-problem like coastal restoration, or the renewal of Lake Pontchartrain, I know we can also join forces and beat the insidious lead menace.