Debra Roberts figured she could handle the boys.

She knew they had problems, sure. Five years of foster care and frequent abuse only amplified a genetic predisposition to mental illness – Mom and Dad’s chance meeting at therapy led to three kids with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia in their bloodline.

But Roberts thought she could easily put her master’s degree in social work to use.

She had a lot to learn.

“It’s a lot. It’s been a lot.” Roberts, 64, mused a few minutes after she shooed the elder two outside her eastern New Orleans home to play basketball. “I’ve lost about 30 pounds.”

The three great-nephews who call her Mom – 11-year-old D’Ron, 10-year-old Ronald and 6-year-old Jamarion – struggle with several emotional and behavioral disorders. Getting them the right academic and behavioral help has been crucial in a city where many schools have failed to properly educate special-needs students and where long-term hospital care for children with mental illness is scarce.

Related: How ReNEW’s SciTech Academy is serving its most challenging studentsChildren with mental illnesses struggle to find help as schools, hospital systems are decentralized

Roberts is fortunate. Staff at the children’s three schools — ReNEW SciTech Academy, ReNEW Schaumburg and Mary D. Coghill Charter School — have done “an excellent job,” she said. ReNEW has provided the most services.

Outside agencies, family and church members have also helped to ease her burden, but it hasn’t been easy. The city’s agencies are swamped with children in need of similar services, and Roberts said it has been tough to deal with long waiting lists and find the appropriate doctors.

Fighting ‘like enemies’

The brothers came to her in June 2013, after she fought for three years to free them from Houston foster care homes.

Before therapy and regular medication, D’Ron in particular was uncontrollable.

“He wants to be over everything. Tell you what to do,” Roberts said. “He feels like he knows what’s best for him.”

Roberts, a woman of slight stature, rejects that notion. “I’m not one who allows children to be in control in my home.”

His defiant attitude, coupled with his bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), led to sometimes violent battles. She’d refuse to buy him everything he wanted at the grocery; he’d run outside to the parking lot and ram shopping carts into cars.

After a particularly wild episode, she tried to coerce him into going to a hospital. “I ended up with bruised ribs, from his head just slamming in my chest, constantly, as I was trying to hold him.”

Children who have undergone severe trauma don’t purposely display these behaviors, said Paulette Carter, president and CEO of the Children’s Bureau of New Orleans. Her organization provides mental health services for 43 of the city’s schools, and the brothers frequently attend the agency’s trauma-focused therapy.

“A kid who experienced the murder of their cousin a few weeks ago – they may be sitting in a classroom, and really just reliving the trauma of that experience over and over,” she said. “The teacher just thinks that the child is not listening, or the child is being disrespectful. But in reality, that child has no choice.”

“A kid who experienced the murder of their cousin a few weeks ago – they may be sitting in a classroom, and really just reliving the trauma of that experience over and over. …“The teacher just thinks that the child is not listening, or the child is being disrespectful. But in reality, that child has no choice.”—Paulette Carter, Children’s Bureau of New Orleans

Roberts says she’s had the most trouble with D’Ron. But in a house full of three emotionally disturbed boys, one impulsive behavior sometimes triggers another.

D’Ron would tap Ronald in that annoying way that brothers do, and run off. Ronald, who also has PTSD and ADHD, hates to be touched — so he’d lunge. They’d fight “like enemies,” Roberts said, with young Jamarion jumping in for whoever he thought was the underdog.

Jamarion, too, has ADHD and what psychiatrists call disruptive behavior disorder. He’s gotten into fights at school. He torched the living room curtains at one of his foster homes.

Past abuse created challenges: the boys struggled to define boundaries and appropriate relationships with adults, Roberts said. A simple gesture or tone of voice could trigger a horrific memory, and the behavior would spiral out of control.

Intensive, in-school support

When she got the children last year, Roberts wasn’t sure where to enroll them. She had gotten a postcard from ReNEW Schools and asked a church member if they were any good. Schaumburg in the East was closest to home, and someone else had mentioned good things about Coghill, in Pontchartrain Park.

She learned of ReNEW’s therapeutic program only when staff referred D’Ron there. Jamarion still receives support from social workers at ReNEW Schaumburg. Ronald attends Coghill.

SciTech’s program, launched in 2011, is aimed at students with severe emotional and behavioral issues. It’s available to students throughout the ReNEW network.

D’Ron and eight other middle-school boys comprise one class. Seven third- through fifth-graders make up another. The program’s teachers have backgrounds in social work and counseling, and a lead counselor provides group and individual therapy for children when necessary.

16Students in ReNEW’s therapeutic teaching program$500,000Annual cost

ReNEW isn’t alone in this work. Its program ends in eighth grade, but high-school charter network Collegiate Academies has its own therapeutic program called Journey. The city’s second-largest charter network, KIPP New Orleans Schools, runs a similar program.

While children with these issues qualify for the highest level of public special-education dollars, “the funds you get from the state, even with that bump, it’s just not significant enough for the level of needs,” Collegiate Academies president Morgan Carter Ripski said.

Forty percent of Collegiate’s private donations this year supported the Journey program, she said.

The ReNEW program costs about $500,000 for 16 students, and a grant from the Institute of Mental Hygiene largely keeps that program afloat, Executive Director for Intervention Services Elizabeth Marcell said. With those costs, it’s probably not surprising that few schools in the city offer such programs.

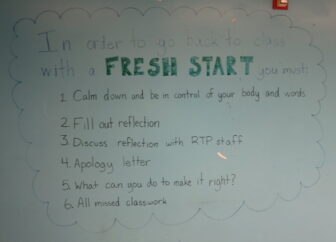

Though Coghill doesn’t offer such intensive services, Roberts says she’s pleased by what Ronald does get. They have a counselor and a space for him to go when he needs to calm down.

A long-term solution is afoot for more schools like Coghill. The Orleans Parish School Board and the Recovery School District inked a deal in March to open a citywide therapeutic program this winter. The two districts also agreed to funnel an extra $6.3 million this school year to schools educating special-needs children.

Path to peace

As the brothers played basketball outside Roberts’ house one May afternoon, there were no shadows of the rocky behavior she described.

Bright-eyed Jamarion, who for most of that hour had been quiet, snatched The Lens’ microphone and headphones to dance and sing his own rendition of a Michael Jackson song.

“I say Thriller! Thriller now! Cursive on the wall, to the threes and to the fours!” (Jackson diehards will note his creative lyrical interpretation.)

D’Ron was equally animated, showing off his jump shot and describing how much he liked learning about the Spartans in history class at school.

A representative of Ekhaya of New Orleans stood with his arms folded, watching the kids play and reminding the older boys to chill out when their jabs got too rough.

That night, representatives from Ekhaya, National Child and Family Services and other support agencies met at Roberts’ house over pizza to discuss how the past few weeks had gone and to come up with a plan for the weeks ahead.

The state pays for that extra support through its mental health provider, Magellan of Louisiana. It offers counseling sessions and hospital stays if needed, according to the Louisiana Behavioral Health Partnership’s member handbook.

The state targets children like these three brothers for care — those with mental health disorders who have been in foster care.

In a city where so many children need help, though, it wasn’t easy to find a provider, Roberts said. Many therapists have waiting lists, and the children finally enrolled in trauma-focused therapy a few months ago.

But now that they have care, their progress is comforting. Roberts knows they have a long way to go. She hopes for less stress along the way.

“I’ve made a decision to do this, so I know God is going to give me a place in my life where I have peace,” she said, laughing. “Lord, if it’s just three hours in a day, give me that peace, so I can carve my space back in my house.”