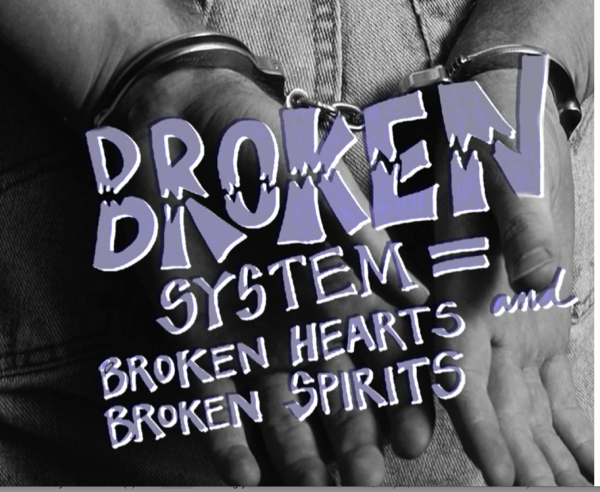

Advocates for young people slipping into the clutches of the criminal justice system took to the steps of the statehouse today and called on Governor Bobby Jindal to stop “backsliding” on his commitment to reform the state’s notorious juvenile justice system and instead support programs that favor rehabilitation over punishment.

In a report called What’s Really Up, Doc?”, representatives of two groups – Families and Friends of Louisiana’s Incarcerated Children and the Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana – expressed particular dissatisfaction with Mary Livers, Jindal’s 2008 appointee to run the state Office of Juvenile Justice.

“Despite claims of reform,” the report charges, “Louisiana is still operating under the traditional, punitive method of juvenile justice.”

Livers has a 30 year history in adult corrections, and “minimal experience in juvenile rehabilitation,” said the report, issued today at noon on the Capitol steps in Baton Rouge. In her three-plus years on the job, the report states, “Louisiana’s juvenile justice system has experienced frightening trends of violence and neglect permeating through the secure care facilities that house Louisiana’s youth.”

Years before her appointment to the Office of Juvenile Justice, Livers worked at the Oklahoma Department of Corrections and for Avalon Correctional Service in Oklahoma, a private firm that operates prisons and juvenile jails.

The report calls for a recommitment by the Office of Juvenile Justice to reforms enacted in 2003 that advocates say have been neglected. Among measures urged by the report:

- Full implementation of youth-justice reforms enacted in 2003.

- Better training for staff in youth-related issues.

- Create regional youth facilities.

- Emphasize community-based rehabilitation programs over incarceration.

- Build smaller dorms in youth facilities to decrease violence and increase staff interaction.

- Improve programming in facilities around the state.

- Greater parental involvement with more direct action from the state to bring parents into the program.

The report reminds state leaders that in 2003 Louisiana passed “sweeping juvenile justice reform legislation that committed the state to a more therapeutic model of juvenile rehabilitation.”

Those reforms came about only after recognition that, as the report states, “the state’s youth prison system was one of the most brutal in the nation.” They followed a U.S. Department of Justice lawsuit against Louisiana over unconstitutional conditions at youth facilities and “well-publicized violence in the facilities,” the report states.

The resulting legislation, Act 1225, committed the state to reforms modeled on Missouri’s well-regarded youth justice program.

The “Louisiana Model” that emerged closely tracked the Office of Juvenile Justice’s Louisiana Children’s Code, which was “crafted with the idea that adjudicated youth are not placed in OJJ’s custody for the purposes of punishment, or to be segregated from society; rather, they are placed in OJJ’s custody for the sole purpose of rehabilitation and treatment,” the report said.

The year Louisiana enacted the reforms, Oklahoma’s Office of Juvenile Affairs terminated the prison management contract with the firm for which Livers worked. One reason cited for the cancelation was the poor quality of education programs Avalon offered to youth, according to a report issued by the Oklahoma Public Employees Association, an opponent of prison privatization.

The youth advocacy groups accuse Jindal of backsliding on commitments to invest in a continuum of services for youth and instead refocusing on incarceration as the principal response to youthful offenders. “It is of great concern that just a decade ago Louisiana was making national headlines about problems in juvenile justice,” said Dana Kaplan, executive director of the Juvenile Justice Project.

“The problems and the violence in the youth facilities has increased” in recent years, Kaplan said, “and there will be serious consequences if there is not real investment in youth services – and greater leadership.”

The American Correctional Association has reported that it costs between $66,000 and $88,000 to incarcerate a youth for between nine and 12 months, far more than the state’s per student allocation for public education.

Kaplan and others have mounted a concerted effort to address the notorious “school to prison pipeline” whereby suspensions and expulsions for minor infractions can lead to criminal offenses and eventual incarceraton. Youth advocates have pushed for school- and community-based programs that divert youthful offenders from prison.

The pro-youth pushback – one wag has dubbed it “No Child Left Behind Bars” – is being undermined by the Jindal adminstration’s enthusiastic prison privatization schemes and further cuts in community-based services – not to mention the absence of ongoing federal oversight of the Office of Juvenile Justice, Kaplan contends.

Part of the 2003 federal settlement required the state to fully fund health care services for youthful offenders, but the agreement expired around 2005, Kaplan said. Jindal ended a contract with Louisiana State University that was providing state-run health care services to youthful offenders and turned it over to private providers.

Over time, Jindal has “consolidated OJJ services with the State Police, slashed funding for community-based services, privatized healthcare in the facility, and cut vocational programming for youth,” the report says.

The Office of Juvenile Justice operates four youth facilities in Louisiana: Swanson Center for Youth in Monroe; the Jetson Center for Youth near Baton Rouge; and the Bridge City Center for Youth near New Orleans. Its website claims to “serve youth in the community who are not involved in our system,” through community services programs at a dozen locations around the state.

The Lens sent a copy of the report to the Office of Juvenile Justice for comment, after the office declined to comment on its contents without first reading it.

A response was not immediately forthcoming.

After reviewing the report, in an email to The Lens the Office of Juvenile Justice defended its performance under Livers, saying it is “completely dedicated to reform of the juvenile justice system in Louisiana.”

“Current data show that our recidivism rates have fallen in all areas (secure care, non-secure, probation field services) and violent incidents have decreased in our secure facilities,” the statement said, adding that the office “has made remarkable progress toward systemic reform, in a short period of time …”