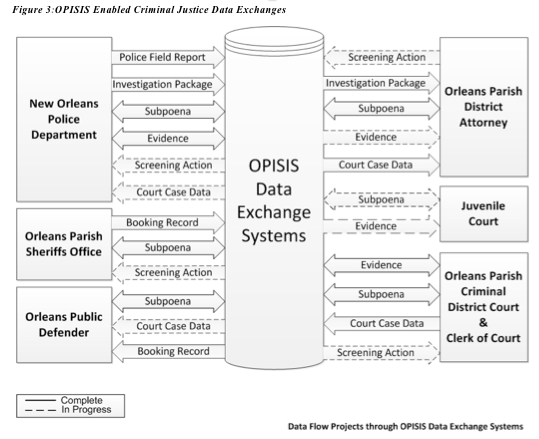

Since Katrina, a private organization dedicated to integrating New Orleans’ disparate criminal-justice computer systems has been unceremoniously accomplishing its goal, mostly by paying for sorely needed technical upgrades that benefit police, jailers, prosecutors, public defenders and the courts.

Now it’s about to embark on its most ambitious undertaking: expanding its centralized system for tracking criminals and their cases and putting it on the city’s main computer system.[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]The New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation has amassed substantial power to direct the course of New Orleans’ criminal-justice computer systems, primarily out of public view.[/module]

But the nonprofit New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation has no written agreement with the City of New Orleans, even as it routinely works with sensitive information. For that matter, the foundation and its technology initiative – the Orleans Parish Information Sharing and Integrated Systems program – have no contractual relationship with the city that would allow it to make the technological upgrades it has been performing on behalf of the city since 2006.

And it faces the added challenge of finding a single agency to house – and pay for – this technology among a fractured criminal-justice system where there are both parish and city officials, some elected and independent, and some appointed.

The foundation has amassed substantial power to direct the course of New Orleans’ criminal-justice computer systems, primarily out of public view.

With almost $4 million in federal and private grants backing it, the foundation morphed from what was essentially a booster organization for the New Orleans Police Department before the storm into the key player in upgrading information-sharing capacities among criminal-justice agencies. The organization has spent $3.35 million on upgrades so far and has about $450,000 in the bank.

Some of the projects undertaken since 2006 include:

- Creating a homicide records archival system for the New Orleans Police Department

- Creating and expanding a comprehensive evidence management system for the NOPD

- Creating an investigative case management system for the NOPD

- Modernizing green-screen legacy systems at the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office

- Expanding the CourtNotify electronic subpoena system

- Creating a public defender case management system

- Performing information-technology enhancements for the Orleans Parish District Attorney’s office

These projects, said senior project manager Nathaniel Weaver, were “mostly focused on implementing software applications to address multi-agency ‘pain points.’”

Now the foundation is ready to take a great leap forward, Weaver said. It now has access to even more information that criminal justice agencies need to improve their efficiency, he said. And, he said, the foundation is working to move all that data over to the main city database.

The enthusiasm for the foundation’s work extends across the New Orleans criminal-justice community. Whether it’s Jon Wool at the Vera Institute of Justice or Rafael Goyeneche at the Metropolitan Crime Commission, you’d be hard-pressed to find anyone familiar with criminal justice who has a bad thing to say about the foundation.

The foundation is now providing the Vera Institute with defendants’ court history, such as their compliance with prior bond terms, in order to help the institute make recommendations for its pre-trial services program.*

It has just completed a system that electronically sends police reports and case information to the District Attorney’s office.

That’s a far cry from a system that once routinely found criminals languishing in jail awaiting the various streams of paperwork to coalesce.

“Mistakes borne from paper-based processes sometime result in violations of civil liberties,” said Weaver, “such as arrests based on out-of-date warrants or failure to release a prisoner once a case is dismissed.”

Now, said Weaver, “we’re on the cusp of much greater changes that I think will reduce improper incarceration and potentially save lives.”

Before Katrina, “agencies built stand-alone ‘stovepipe’ applications that didn’t communicate well or within agencies,” said Mayor Mitch Landrieu spokesman Ryan Berni.

“Prior to this administration, the city of New Orleans did not participate in criminal justice IT issues,” he said. “The New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation sought and obtained federal and private funding to help fill the gap by implementing shared information systems across multiple justice agencies.”

But the ad hoc partnership with City Hall raises questions about privacy, accountability, and oversight:

- To whom does the foundation answer?

- Who is making sure that private information stays private?

- Who should guide continued development of these mutually beneficial systems?

- What agency is going to pay for the continuing upkeep of the foundation’s work?

The federal government raised some of those concerns two years ago. In early 2011, the Integrated Justice Information Systems Institute, a nonprofit providing research on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice, issued a report praising the foundation’s work. The department has provided the lion’s share of resources to the foundation project, so its support for the program is not surprising.

But the report noted that the effort’s “governance authority is informal and is likely to become inadequate” for the major work anticipated. The report said the foundation has installed new systems “with the absolute minimum of formal agreements among participating agencies under the assumption that negotiation of such agreements would introduce serious delay and other complications. The OPISIS Program, nor the participating agencies, can expect to continue operating in this manner without a funding commitment.”

Two years later, little has changed regarding the funding or governance of the foundation’s technology initiative, which has been overseen by Michael Geerken, Chief Administrative Officer under former longtime Orleans Parish Criminal Sheriff Charles Foti. The foundation, Weaver said, is working off of four main funding streams: congressional appropriations run through the Department of Justice; a three-year grant from Baptist Community Ministries; $130,000 in federal grant money administered by the city’s Criminal Justice Coordinating Council; and two small grants from the Wisdom Foundation.

Foundation volunteers transparency

Officials at the New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation say the organization is committed to a spirit of transparency when it signs contracts with tech vendors to do work on behalf of New Orleans’ criminal justice agencies. Since launching its first tech project in 2006—the creation of an emergency backstop computer system at the Orleans Parish jail—the foundation has signed seven contracts with vendors such as Orion Communications and Column Technologies.

“One of our major goals in OPISIS is to improve transparency, so it would be ironic—and unacceptable—if the process itself was not transparent.”–Nathaniel Weaver, New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation

But it’s best described as voluntary transparency because any information the nonprofit foundation releases to the public is a matter of discretion, not a requirement of public records laws.

It wasn’t until late last year that the foundation said it would ramp up its transparency efforts.

Last summer, the foundation issued a request for proposals through its website, looking for a company to move its complex and dynamic database to the city’s data center.

The foundation’s database now is housed at the New Orleans Police Department, and the foundation needed to reconfigure applications already in use by criminal justice agencies in order to accommodate its database.

A request for proposals to perform the migration yielded bids from two companies, Sierra Systems and Geocent.

The Lens wanted to look at the proposals. But Sierra Systems first told the foundation that its submission was a proprietary document, and then asked that any personal information be redacted from the proposal as a condition of release to the public.

Late last year, once it had provisionally won the contract, Sierra requested that its bid be kept secret until it had signed off on the deal, which had been scheduled to take place after Carnival.

The Sierra bid was scored by the foundation and, critically, by city employees, according to documents, and the foundation planned to sign off on a $100,000 contract. But the scheduled deal was scotched earlier this year, said Weaver, owing to a raft of technical issues.

In the meantime, Weaver had contacted Sierra and gotten them to drop their privacy demands.

Weaver said the foundation would change its bidding rules moving forward. Future bid requests, he said, will include language saying that information can be released at the discretion of the foundation.

“That way we can avoid this issue in the future.” Weaver said. “It’s just not something that has come up in the past. One of our major goals in OPISIS is to improve transparency, so it would be ironic—and unacceptable—if the process itself was not transparent.”

Accountability and privacy

The specter of a nongovernmental organization having access to personal information on the city’s computers is exactly why organizations such as the New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation are often tagged with the unwelcome sobriquet, the “shadow government.”

The tag draws a knowing chuckle from Weaver, who insists that the organization has instituted checks against shenanigans. He says the group has built safeguards limiting access to personal information. The foundation’s contracts, he added, have provisions to protect privacy and restrict the use of the data by contractors.

Furthermore, only one foundation employee, software developer Eddie Branch, has access to the entire database, Weaver said. Branch is a reserve New Orleans police officer, he said, who has gone through a background check.*

Still, the foundation’s work goes on largely outside the usual scope of accountability, even though documents abundantly demonstrate a working relationship between the foundation and city officials in the Office of Information Technology and Innovation.

The official line from City Hall is that the foundation isn’t working for the city.

“The New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation is not signing a contract or doing business on behalf of the city,” said Landrieu spokesman Berni, speaking on the proposed Sierra contract before it was scuttled.

But employees of the city of New Orleans were directly involved in the Sierra Systems proposal, according to emails obtained by The Lens. At least one thought Sierra was the wrong choice.

In an email to Weaver, city employee Lamar Gardere said he “was swayed by Geocent’s specific knowledge of ITI and NOPD environment and the feeling that we may be able to negotiate a lower price based on previously delivered exploratory work.”

Gardere’s opinion did not sway the rest of the selection committee, which included other city IT workers and members of the foundation’s tech team.

In another email from late summer, a city information-technology contractor, Bill Garbee, warned other employees involved in the bid evaluation to “keep these documents confidential and do NOT distribute the documents to anyone else as the evaluation is ongoing and no decision on award has been made.”

Typically, decisions about the public’s right to check out bids under review by the city of New Orleans emanate from the City Attorney’s office, and not from the email account of a contract worker.

Berni told The Lens that the city had evaluated the Sierra bid, raising again the question of whether the foundation was soliciting bids on behalf of the city.

The foundation’s information-sharing project, while lacking in a formalized governance structure, does identify a set of committees. The Technology Committee includes IT heads from the agencies it works with, and includes New Orleans’ Chief Information Officer Allen Square. Documents obtained by The Lens indicate an ongoing relationship between the city’s information technology staff and the foundation’s technology architects.

The executive board for the foundation’s program includes leaders from criminal justice agencies in town–Sheriff Marlin Gusman, Police Superintendent Ronal Serpas and others. The foundation has individual memos of understanding with each of the agencies, but the executive committee has no oversight role and merely helps to set priorities.

There’s also a Project Management Office that oversees the efforts–but that office is the police foundation itself.

The governance issue might get squared up if the city takes the advice of that Justice Department-sponsored study and enfolds the data-sharing system somewhere in the city bureaucracy.

The 2011 report said the lack of clear authority could lead to internecine squabbling that could delay or disrupt the project. It noted that the city’s Chief Information Officer floated the idea of having signed cooperative endeavor agreements between the foundation and each participating agency. Instead, they signed informal memos of understanding.

Weaver said the foundation is looking at options for a future project home in the city bureaucracy. One plan would embed it within the city’s Office of Information Technology and Innovation. Another would make the project a subcommittee of the New Orleans Criminal Justice Coordinating Committee, an executive committee under Landrieu’s control. The least likely option, he said, would be to create a charter organization similar to the Orleans Parish Communication District, which runs the city’s emergency-calls services.

The federal report stated that under the present, nonformalized arrangement, the city ends up with “unanticipated maintenance costs that are not covered” after the system is installed.

The report recommended that the program strive to get its funding through local government.

“We won’t be able to run it on federal and private grants forever,” Weaver said.

But Geerken warned against rushing to bring the project into the city bureaucracy. The foundation’s independence is crucial to the project’s success, Geerken said, given the historical climate of mistrust among Orleans Parish criminal justice agencies.

Most of those agencies were fumbling around in an ancient wilderness of green-screen legacy computer systems before the foundation offered help, said Geerken, who insisted it would be unwise to cede control of the technology-sharing project to one or another criminal justice agency.

“We’re a neutral arbiter,” Geerken said. “We’re not allied with any of the agencies. And the reason we are moving slowly toward evolving the governance model is that we are extremely sensitive in maintaining the trust relations we’ve built among the criminal justice players.”

Correction: This story originally misstated Eddie Branch’s position with the New Orleans Police and Justice Foundation. He’s an employee, not a contractor. It also inaccurately described how the foundation is sharing data with the Vera Institute. Both errors have been corrected.