By Matt Davis, The Lens staff writer

In an unusual move, Mayor Mitch Landrieu awarded Orleans Parish Sheriff Marlin Gusman a contract in October for more than Gusman originally bid – and for more than the lowest bidder for the same deal.

The contract was for electronic monitoring of some juvenile and municipal court offenders with ankle bracelets. Though the sheriff is in charge of running the jail, an outside contractor has run the monitoring program since 2007.

Mayor Ray Nagin’s administration took two rounds of competitive bids for the services in September 2009 and March 2010. The company with the contract, Total Sentencing Alternatives Program, was criticized for reportedly leaving offenders out on the streets to commit serious crimes, despite having breached the terms of their probation. Nagin’s administration cancelled both sets of bids, leaving the matter to Landrieu.

Gusman was among the bidders both times. And though the process was canceled because of procedural questions, the amounts quoted by each bidder have become public.

Landrieu gave the contract to Gusman’s office through a cooperative endeavor agreement, without a competitive bidding process, on Oct. 15.

The agreement calls for a higher rate than Gusman bid, and it’s also considerably higher than the lowest bidder in the canceled bid requests.

Deputy Mayor of Public Safety Jerry Sneed issued a written statement in response to several requests for an interview with an administration member, saying the agreement was done “to quickly provide the courts with an effective alternative to incarceration.”

The agreement “represents a good value for taxpayers, including a $50,000 monthly cap for the services,” he wrote. “As important as the value, this CEA gives the criminal justice system a more effective internal tool as we believe the Sheriff will be able to work with the courts and other law enforcement agencies to run the most effective program possible.

“We will continue to evaluate this CEA and its effectiveness and make any corrections needed to ensure the safety of our citizens and the proper expenditure of taxpayer dollars.”

A spokesman for Gusman said the sheriff was unavailable for comment.

Inspector General Ed Quatrevaux took Nagin to task in a letter for canceling the bid process.

“Since 2006, the city has paid more than $4.7 million for electronic monitoring services and the cost per participant per day has almost doubled in less than four years,” Quatrevaux wrote. “Given the city’s current economic circumstances, it is critical to make every effort to obtain the best possible deal for taxpayers under the new contract.”

Quatrevaux recommended that the city cancel the second bid, then put the contract out to bid again, and award the contract to “the lowest responsive and responsible bidder.”

Quatrevaux’s office declined comment for this story.

At least one unsuccessful bidder appears less than amused. G4S Justice Services vice president Leo Carson wrote, faxed, and e-mailed Landrieu’s office on Sept. 28, formally requesting the opportunity to compete for the contract.

Carson drew Landrieu’s attention to the city’s policies on competitive selection, asked for the city’s “specific justification to sign this contract with the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office without first competing it via RFP or RFQ,” and suggested that the city would be discriminating against other bidders on the contract by giving it straight to Gusman.

Carson also wrote that the previous bidding process had emphasized specialized experience and technical knowledge, and asked for the city’s “specific justification for independently signing a contract, and paying a higher cost, for other than the best possible contractor for this vital public safety contract?”

Carson declined to comment further on the contents of his letter when contacted by The Lens, but public records support his assertion that Gusman’s office was not the lowest bidder on the contract.

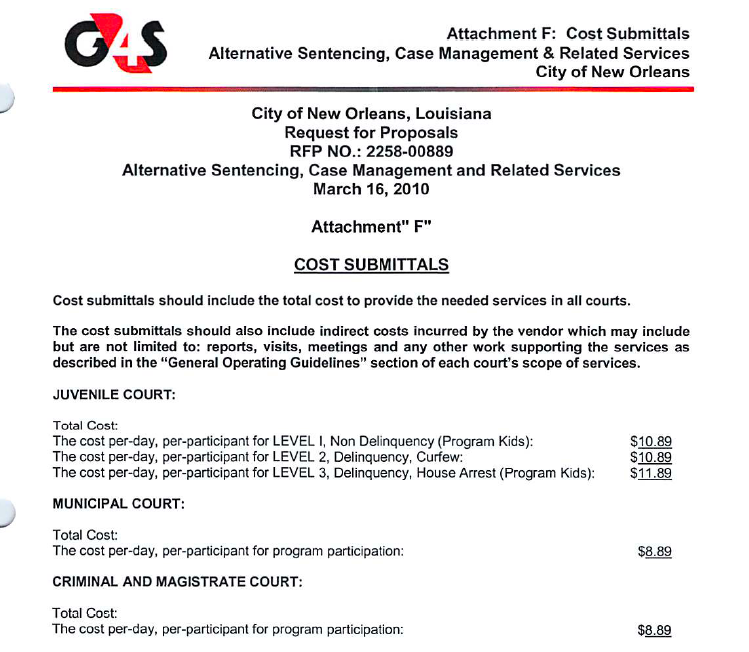

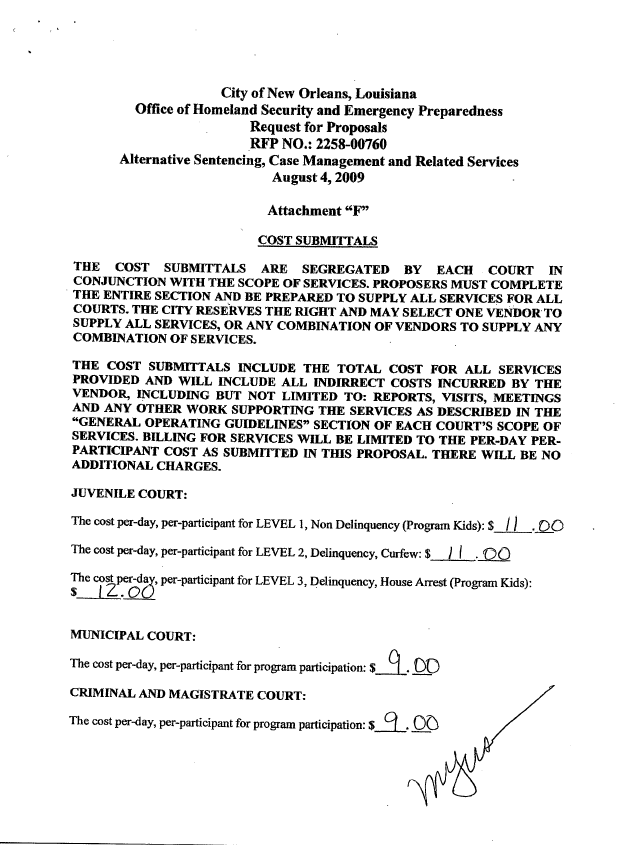

In late 2009, G4S Justice Services bid $13.83 per participant per day for juvenile court participants, and $13.75 for municipal, criminal and magistrate court participants. But in early 2010, G4S reduced its bid to between $10.89 and $11.89 a day for juvenile court participants, depending on severity, and $8.89 per day for municipal, criminal, and magistrate court participants.

Meanwhile, Gusman’s office has raised its price for the services three times since last year.

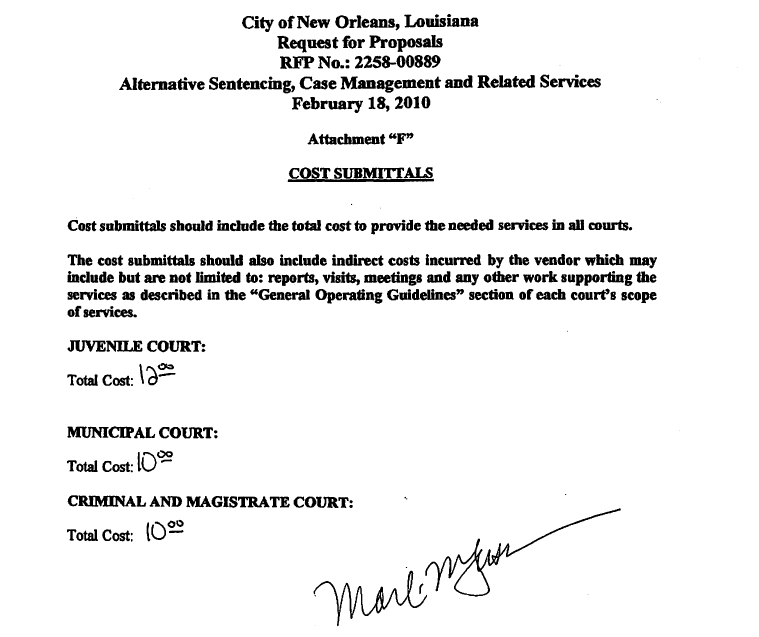

In late 2009, Gusman’s office bid $9 per participant per day for municipal, criminal and magistrate court participants. It also bid between $11 and $12 a day for juvenile court participants, depending on the severity of their case. In early 2010, Gusman’s office bid $10 a day per inmate for municipal, criminal and magistrate court participants, and a flat $12 a day for all juvenile court participants.

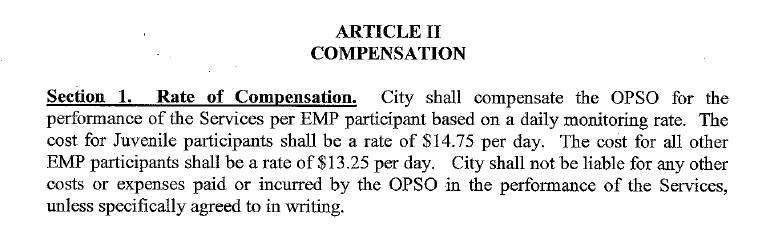

The cooperative endeavor agreement now pays Gusman $14.75 a day per juvenile court participant, and $13.25 a day for all other participants in electronic monitoring.

Some criminal justice reform advocates are raising their eyebrows.

“It seems like we’re not playing by the rules,” said Norris Henderson, executive director of Voice of The Ex-Offender. “If the rules say a contract for professional services should go out to bid, then it should go out to bid, pure and simple.

“The sheriff has no experience running an electronic monitoring program. He’s even having difficulty running the jail,” Henderson said. “It seems like they’re trying to give the sheriff more sources of revenue to appease him, because they’re realizing that they can’t build a huge new jail as the sheriff would have liked.”

Landrieu’s office has also convened a working group to look at an appropriate size for Gusman’s new jail, potentially reducing the amount of money the sheriff’s office gets paid per inmate, per day, if it reduces the 5,800 inmates called for in Gusman’s April submission to the city’s zoning board.

Landrieu also pounded Gusman’s office in his proposed budget, released on Oct. 15: Gusman asked for $36.3 million, but Landrieu submitted a request to the City Council of only $22.7 million. The council will vote on a final budget Dec. 1.

Elsewhere, there is support for Landrieu’s decision.

“One of the shortfalls of having a private contractor doing these services is if somebody is in violation the terms of their release, then the only thing the contractor can do is notify the judge,” Metropolitan Crime Commission leader Rafael Goyeneche said. “With the sheriff’s office involved, which has arrest authority, if there’s a significant violation, they can go out and immediately apprehend that individual and bring them in.”

Landrieu’s office is “making a decision not just based on the bottom dollar financially, but on the public safety impact,” Goyeneche said.

Landrieu instituted increased transparency for the city’s contracting in July, and vowed to “institute a new way of doing business…to restore credibility and faith that the public should always have in the way government handles its money.”