See a Lens-produced map of projects Landrieu is pursuing, as well as those he’s not. Please allow a few moments for the file to load.

See a photo slideshow of other projects not being immediately financed by Mayor Mitch Landrieu.

Maddie Trepagnier can’t remember exactly when she gave up on City Hall.

Maybe it was when no one could explain why the city-owned Digby Park in her eastern New Orleans subdivision wasn’t getting fixed up, even though FEMA had obligated money for it. Or maybe, she said, it was when no one returned calls about a spewing water main flooding her block. Or when she saw rebuilding dollars pay for palm trees in less-affected parts of the city, while the road leading to her neighborhood was barely passable.

Her lack of faith makes sense given her surroundings. It’s difficult to tell five years have passed since Hurricane Katrina’s floodwaters pushed down the levees and flooded 80 percent of the city, including Trepagnier’s neighborhood. Looking around, it may as well be just a year or two after the storm.

An abundance of vacant homes give her block a checkerboard look. Construction workers smoke cigarettes outside trailers parked on muddy lawns. And if you start talking about the city’s future, good luck at avoiding jargony post-disaster phrases such as “shrinking the footprint” and turning a neighborhood into a green dot.

“If often feels like we are being punished for coming back to our homes,” she said on a recent evening, following a civic-association meeting in her freshly repainted living room. Hours earlier, Mayor Mitch Landrieu had announced that the neighborhood’s park would finally be rebuilt with the $122,969 in FEMA money that residents had begged the previous administration to spend.

“It was a victory that should not have been this hard to win,” Trepagnier said.

The park was among the 100 projects (pdf) on city property that Landrieu recently released and committed his administration to completing. It was welcome news to a city eager for a detailed plan after years of former Mayor Ray Nagin’s vague, bellicose promises and anemic follow through.

But the list of Nagin-era projects that Landrieu did not immediately commit to starting, let alone finishing, is just as revealing for a city still on the mend. Along with a list of finished or nearly finished projects frequently touted by the city, and a state-generated status update of FEMA-financed projects worth more than $55,000, The Lens has put together one of the most complete accountings of the city’s efforts to revitalize its own properties and improve the lives of residents, employees and visitors.

The records illustrate the winding, red-tape-ridden road New Orleans has traveled over the past five years and see more clearly the priorities of the previous administration.

OF CLIPBOARDS AND RESPIRATORS

The streetlights were still out when FEMA field workers arrived in New Orleans to assess hundreds of damaged or destroyed city-owned facilities. Wearing respirators, these federal employees or contractors treaded through molding buildings and sodden parks with engineers and city employees or contractors. Their job was to make sense of what Katrina’s wind and the subsequent flooding had done to these facilities so they could document the cost of repair, or wholesale replacement, in worksheets assigned to each project.

The 655 project worksheets (pdf) that came out of those chaotic early days and the hectic months that followed would be the foundation for all damage claims payable by the federal agency to the city. But as virtually anyone who was working with the city at that time recalls, the worksheets set a relatively low basis for reimbursement. In short, the city was low balled.

“Someone underestimated,” said John Marini, chief operating officer for a disaster recovery consulting company, Adjusters International, that was hired by the city in the immediate aftermath to expedite negotiations with FEMA. “They didn’t take into account latent damage. They didn’t realize how old the buildings were and how that would add millions to the cost of renovating.”

The process ended with the city establishing project worksheets for 655 projects. (pdf)

Even before Landrieu marked his first 100 days in office by releasing the sure-thing100 projects, 70 of them non-road projects, he warned residents that it was time to scale back expectations to fit government’s modest post-recession, post-Nagin checkbook.

Landrieu’s practical approach — the term compassionate pragmatism comes to mind — received widespread approval across most of the city.

“It’s better now to know, for real,” said Councilwoman-at-large Jackie Clarkson at a press conference announcing the mayor’s 100-project plan, “to say this is what you will have, and this will be what you won’t have.”

His point man on the city projects did his best to bring people back to earth.

“It was clear off the bat that everything everybody imagined wasn’t going to get done. I want to inject a sense of reality about this. There’s a lot of dreaming going on here,” Deputy Mayor for Infrastructure Cedric Grant told The Times-Picayune earlier this month. “I don’t see a boatload of money coming. We’re at the point where this is what we get.”

Grant told The Times-Picayune that 273 projects of the 655 recovery projects tracked by the city are completed or are nearly completed at a total cost of $367 million.

When a list of these projects was requested by The Lens, the city provided a summary of 270 projects (Excel) ranging from minor jobs such as a repair of an elevator in Criminal District Court, or the repair of sidewalks in the French Quarter, to large projects, such as the renovation of Mahalia Jackson Theatre for the Performing Arts. No project costs were included on the list supplied by the city.

The handful of larger projects correlate to the state list of FEMA-financed projects, though that list shows that only seven reconstruction projects have satisfied state requirements for being considered complete.

The mayor’s to-do list reflects a commitment to building the city back with a more concentrated urban grid in mind, as well as an awareness of needs in lower-density sections of the city. For instance, Landrieu chose to build back all major public facilities in the Lower Ninth Ward, as well as many projects in the east, including Trepagnier’s Digby Park.

But instead of scattering resources between various human service facilities in Hollygrove and Carrollton, a large $1.8 million senior center with a health clinic and a community facility is planned to rise. Similarly, a pre-storm health clinic in the Desire/Florida section of the Ninth Ward will be replaced by a larger $12 million multi-service center.

Even with these big ideas evident behind the modest plan, the vision is best described as a compromise.

“We are all going to have to make sacrifices,” Kristin Palmer, City Councilwoman for District C, said.

Analysis shows that the council district that includes the Lower Ninth Ward and eastern New Orleans, City Council District E, is on tap to receive the largest allocation of FEMA money — $47 million. Bringing up the rear is District D, which includes Gentilly as well as parts of the east, the Upper Ninth Ward and the Seventh Ward, with $13 million for rebuilding facilities. Pre-storm realities determined the flow of resources – as the post-storm refrain went, FEMA cannot build better; it can only build back.

MANY PROJECTS NEED TO BE UPDATED

Yet as residents grow used to continuing life in a city that is neither quite the New Urbanist Xanadu envisioned in the many lofty planning meetings right after the storm, nor a refurbished version of the old New Orleans, a look at state records raises new questions about how many of these projects could’ve come back to life if the city had negotiated more effectively with FEMA earlier on.

Landrieu holds out hope that he can still bargain with the feds.

In the five years since the failure of federal levees sent 8 feet of water surging into Trepagnier’s neighborhood, FEMA has committed about $600 million to New Orleans for rebuilding public facilities and infrastructure — roads and bridges, pumping stations, parks, community centers, courts, libraries, health clinics, police stations and fire houses. About a third of that, $232 million, has been set aside to pay for buildings and parks, while the remainder will pay for roads, bridges, pumping stations, drainage facilities and emergency protective measures and debris removal, an analysis of city records shows. Before negotiations on infrastructure and facilities are complete, another $300 million is expected to flow down, said Mark DeBosier, disaster recovery chief for the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness. All FEMA money passes through the state to reach New Orleans. DeBosier handles that transaction.

Even with this money, the city has not managed to complete more than a handful of projects.

Only seven of the city’s 333 FEMA-funded major reconstruction projects – including roads, bridges, pumping facilities and drainage but excluding emergency protective measures and debris removal – are complete, records from the Governor’s Office of Homeland Security and Emergency Preparedness show. The list includes a new Emergency Operation Center for the city, fueling stations for city vehicles, the Orleans Parish Criminal Courts Building and other public safety infrastructure as well as work on pet projects of former Mayor Ray Nagin: Louis Armstrong Park and the Mahalia Jackson Theatre.

The longer list of 270 complete or nearly complete projects provided by the Landrieu administration includes road repairs and smaller facility repairs.

“Those are things like a roof on a small building or an air-conditioner or elevator,” DeBosier said. “From a recovery standpoint, they are almost non-issues.”

None of the rebuilt major facilities lie within the sections of the city most devastated by Katrina.

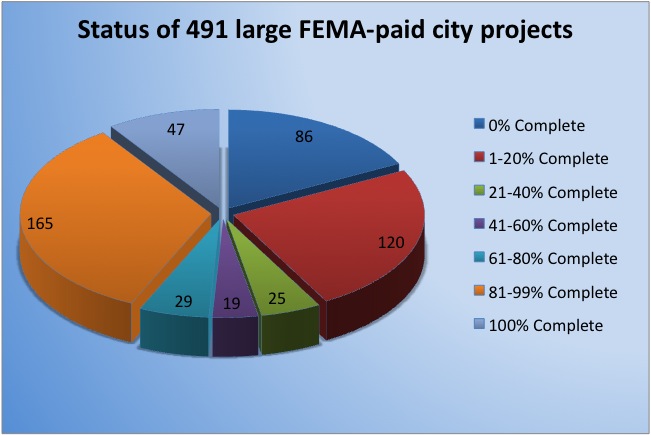

The state lists the projects somewhat differently, with some combination of city projects and breakout of others. So while the city is tracking 655 projects, the state figure is 491.

Five years later, a majority of the city’s 491 total project worksheets (Excel) have never been fully updated, state documents obtained by The Lens show. This means that FEMA has not revised early damage assessments to reflect years of inflation, or even the fully vetted cost of repairing old facilities that in many cases were more damaged than initially realized.

The documents show that 14 percent of the city’s 491 FEMA-funded projects are still being funded according to the initial assessment done immediately after the storm. Another 43 percent are in line for funding based on a first or second revision.

In stark contrast, the worksheet for the City Hall building, a priority for the last administration, was revised eight times, the NOPD building was revised nine times, and Orleans Parish Prison was revised 10 times.

Left unremedied, the failure to update more assessments could cost the city the hundreds of millions of dollars – and the option of paying for all 655 recovery projects, rather than restricting rebuilding to the 100 priority projects in the pipeline and the 270 complete and nearly complete, said Nagin’s former Capital Projects Administrator Bill Chrisman.

“You can say the projects are under budgeted, but that is because the worksheets are based on numbers from 2005,” Chrisman said.

CITY SEEKS TO FOLLOW SCHOOL DISTRICT’S LEAD

Chrisman said he left City Hall after a series of disputes with other members of the Nagin administration about how much money the city was spending on consulting contracts. One 2009 consulting contract that Chrisman approved of, however, went to a firm hired to work with FEMA on those project revisions. Chrisman estimates that the work earned the city $250 million in revised assessments, with another $100 million in the pipeline, before the consultants’ contracts ended when Mitch Landrieu became mayor.

He estimates that the original project worksheets, before any revisions – or “reversionings” in FEMA-speak — are done, cover about 30 percent of 2010 costs.

“What the city got from FEMA in the first three or four years after the storm was essentially chump change,” he said. “It was in the reversioning that the real dollars came in.”

Landrieu seems to understand this process. At a press conference announcing his 100 priority projects, the mayor explained that he is only going forward with projects that have “been through the mill with FEMA.”

If a project is not on the list “it could mean still in a discussion phase with FEMA, still in version phase,” he said, adding that his administration will continue to negotiate “so we can make sure that we get every dollar the federal government owes us.”

Although Landrieu said he is up for the challenges of negotiating with FEMA, it remains to be seen how much human capital he is willing, and able, to put into what is sure to be a massively laborious burden for a cash-strapped city with a workforce already compromised by furloughs and mandatory paycuts.

This summer, the Landrieu administration requested that FEMA reassess only one project worksheet, FEMA records show.

The Recovery School District, by way of comparison, requested seven reassessments.

A federal official suggests that the city, not the school board is the aberration. In response to a question from The Lens about the city’s success with the reversioning process, Rep. Joseph Cao’s spokesman, Taylor Henry, wrote in an email: “Re-versioning, in many of the applicants in the region, were very successful and continue to advance the obligations and recovery.” He went onto add that “the city of New Orleans continues to move the re-versioning process forward, but in the current administration, a new pair of eyes and team members may be what will make the difference as they communicate the level of expectation and pace needed for the city to recover.”

“Within the framework of two administrations encompassing a transition from Mayor Nagin to Mayor Landrieu, the level of engagement has increased dramatically,” Taylor wrote.

Recovery School District Budget Director Ramsey Green said that the district “spent 2008 and half of 2009 versioning all the project worksheets” before settling with FEMA on a lump sum payment of $1.8 billion covering all the damages laid out in the revised project worksheets.

“You want to make sure you get your dollars up before you agree on a settlement,” Green said.

Neither FEMA nor the city responded to public records requests for correspondence between each other and neither entity responded to questions about the reassessment of project worksheets.

What is known is that the city is pushing FEMA for a single settlement, like the one won by the school district and paid out this week.

“The lump-sum settlement could help us move faster on projects,” Landrieu spokesman Ryan Berni said.

FEMA declined to comment on the ongoing discussions.

In the meantime, budget woes have motivated Landrieu to cut down on contracts with outside consultants such as those handling FEMA revisions for the Nagin administration. Adding to the complications is the unfortunate fact that FEMA requires stringent documentation of all project spending – something that, from all indicators, City Hall, does not have.

Lower Ninth Ward organizer Vanessa Gueringer released a small, tight smile when asked if she is pleased that big projects in the Lower Ninth Ward – the C.J. Pete Sanchez Center and the neighborhood’s long-neglected playgrounds are on the mayor’s 100-project priority list.

“Finally,” she said. “And if they weren’t on that list,” Gueringer adds, “they would be hearing from me.”

Even so, there are other infrastructure repairs she continues to wait on, things like a stretch of Poland Avenue between Galvez Street and Claiborne Avenue where she said the street lamps don’t work.

In February, Gueringer filed a complaint with New Orleans Inspector General Edouard Quatrevaux asking his office to investigate the whereabouts of recovery dollars for the Lower Ninth Ward. The investigation never progressed but the question is still out there, and with it, a fiery challenge to the city’s new leadership.

“We were the poster child of this disaster for FEMA, for everyone,” she said last week, speaking to a reporter over a plate of meatloaf at the Lower Ninth Ward’s lone restaurant, Holmes One Stop. “We see now that the money we got from putting our faces out there is being spent elsewhere and that is not something we plan to plan to stop fighting no matter how many anniversaries go by.”

I have to admit, this article has confused me while illuminating several points. Let me see if I have them correct:

1. Nagin spent a lot of money on contractors who tried to get more money from FEMA.

2. This is why not a lot got done in 5 years.

3. This also broke the budget, meaning Landrieu has to stop the contractors for “reversioning,” meaning the city may get less money from FEMA.

4. That less money means the city can only fix certain things, not all the projects Nagin promised.

5. People are complaining about that.

If those are correct, I have three comments/questions:

A. How many city or state governments, when faced with a disaster, spend five years in the reversioning process, risking the Federal recovery money in the process? I doubt cities in Florida or North Carolina or Mississippi took that long, which may explain why they appear to recover quicker from multiple disasters.

B. How long should the city wait to spend recovery money on projects that may be more successfully completed with a reversioning? Because reversioning sounds like a self-perpetuating structure to make contractors money: FEMA offers X dollars; city reversions project plan for six months; FEMA offers Y dollars; project now has to be reversioned because previous reversions did not take into account wear and tear of six extra months of no-work; repeat.

C. Since some areas of the city were affected by the flood worse than others, and more likely to have been neglected before the flood. Therefore projects in those areas would more likely be those requiring more time in the reversioning process. Was it the continual reversioning process that kept recovery dollars out of the Lower 9th Ward and New Orleans East?