Since engineers first proposed diverting water from the Mississippi River to rebuild Louisiana’s sinking coast, they have held firm to this axiom: The more water that moves through a diversion, the more land-building sediment that flows into wetlands.

Fishing groups oppose diversions for this reason, fearing that massive plumes of cold, fresh water would force fish and shrimp to distant locations and kill oysters.

But new research reveals that axiom isn’t always correct: There are times when a lower river carries more sediment than a higher one.

Brad Barth, operations assistant manager at the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, said that discovery is the result of ongoing work with the Water Institute of the Gulf about how to optimize diversions by moving the most sediment with the least amount of water.

“Optimization means finding out when to open it, how often and for how long to get the most land-building with the least impact on the fisheries,” he said. “We’ve still go a lot of work to do, but we’re encouraged by what we’ve learned so far.”

This finding comes on top of recent research that shows diversions can be more effective when paired with a pipeline that pumps sediment into an area. This two-pronged approach causes wetlands to build more quickly, reducing the amount of freshwater that flows into fishing areas.

The rule that high volumes always mean more sediment was embedded in the original Coastal Master Plan in 2007 because it was based on research more than 50 years old.

Officials said at the time that diversions couldn’t be planned before they had new research on the river. That study has provided a number of surprising findings, including how much sediment the river carries at different times of the year, at different water levels and at different locations.

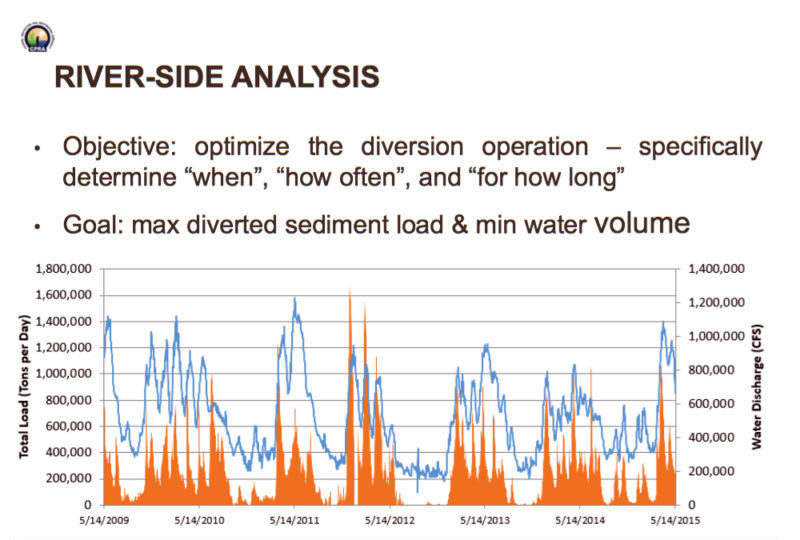

Barth said graphs plotting the measurement of water and sediment at the same locations over five years clearly shows there were times when more sediment was moved at lower river levels than at higher levels.

That could affect not only when a diversion is opened, but how long it would have to remain open.

For example, the agency plans to open diversions between November and April, which would capture the high water months and avoid the peak fishing period along the coast. The new research could allow the agency to coordinate diversion openings to the times when the most sediment is moved with the least amount of water.

“We might be able to time it to get as much or more sediment on fewer days, reducing the impact on the natural resources on the basin side,” Barth said.

He said updated information from the new study will shape plans for the state’s first sediment diversion at Myrtle Grove, about 25 miles south of New Orleans.