A lab in Grand Isle will use a federal research grant to breed high-end oysters that can be harvested year-round, are resistant to diseases and can survive in water too salty for traditional oysters.

These genetically enhanced oysters are unlikely to become cheap enough to end up in your fried oyster po-boy. But when combined with certain farming techniques, they could expand the “sweet spot” of coastal waters where the shellfish thrive, giving oystermen another way to adapt if the state’s efforts to rebuild the coast make waters near shore inhospitable.

The $87,600 grant from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration builds on a Louisiana program that for the last five years has added diversity to the oysters harvested in Gulf Coast states.

That’s when oyster scientists in Louisiana finalized a way to commercially distribute triploids, which are bred to have three sets of chromosomes rather than the naturally occurring two.

Most oysters use up their stored fat to reproduce, making them scrawny and watery in summer months. Triploids, however, are sterile, so they retain their meatiness from June through November.

That allows harvesters to sell a sweet, hearty product during the months that don’t end in “R,” when sales typically wane.

“That’s what people want to eat,” said John Supan, the principal investigator for the project. “Because they’re so plump and meaty when wild, diploid oysters normally aren’t.”

Supan, a bivalve researcher for Louisiana Sea Grant and LSU AgCenter, brought these specialty oysters to Louisiana about 25 years ago. He spearheaded the program to make them commercially available and has been breeding them at a laboratory on Grand Isle, in a hatchery owned by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries.

After much experimentation — and setbacks from Hurricanes Katrina and Gustav — Supan got a good breeding stock about five years ago. That’s when oyster farmers were able to buy seed for triploids.

Since then, triploid oysters have been sold to high-end restaurants and farmers markets to eat raw.

Grand Isle Sea Farms, one of the few businesses that grows these specialty oysters, sells them to restaurants by the box, clean and ready to shuck.

Because these oysters are grown off the bottom, in floating cages, they take in a greater range of nutrients and less silt, said Boris Guerrero, of the family-owned business. “The taste, it’s like a floral kind of flavor,” he said.

Research to avoid inbreeding

NOAA awarded $9.3 million to develop marine and coastal aquaculture industries throughout the country in order to reduce dependence on imported seafood.

The grant for the Louisiana project will fund research to expand the genetic diversity of these oysters, which will allow Supan and other researchers to tailor triploids to thrive in areas of the Gulf of Mexico unsuitable for most oysters.

The research is designed, in part, to avoid the problems that come with a small genetic pool: inbreeding.

Triploids are “so plump and meaty when wild, diploid oysters normally aren’t.”—John Supan, who’s researching development of genetically enhanced oysters

“That’s why incest is a crime. It causes genetic problems down the road,” Supan said. “We’re trying to improve the overall line, the broodstock line we’re developing for the Gulf of Mexico.”

Researchers are also working to create oysters that can tolerate high salinity. Water that’s too salty introduces predators and various kinds of diseases, such as the potentially fatal dermo disease.

Supan said he has “anecdotal evidence” that he’s been able to create oysters that are more resistant to dermo. He points to oysters he bred that are now five years old.

“They should have died three years ago. They’re now the size of your shoe,” Supan said. “Obviously they have some resistance to dermo because they’re still alive.”

The disease-resistant oysters he referred to are tetraploids, a type of genetically enhanced oyster that has four sets of chromosomes.

They, too, remain scrumptious year-round. But they’re not supposed to be eaten because unlike three-chromosome oysters, they can reproduce. Researchers mate them with naturally occurring diploids to create the triploids.

Tetraploids are “your prized bulls,” Supan explained. “You don’t slaughter your prized bulls.”

Sold one by one, for twice as much as regular oysters

The hatchery shuts down in the winter for maintenance. Beginning next year, triploid seed and larvae will be sold by the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries to commercial nurseries and growers.

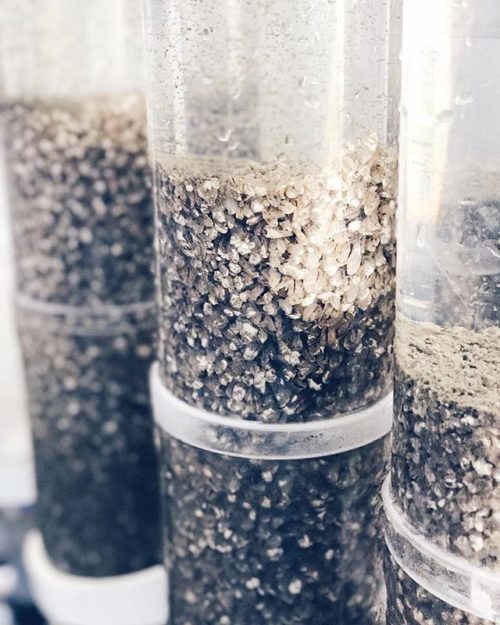

Triploids are raised by oystermen in floating cages or bags. That protects them from predators like oyster drills, little snails that prey on small shellfish by boring holes through their shells.

This type of cultivation is a lot more expensive than harvesting run-of-the-mill oysters, which grow in clumps on the water bottom.

Triploids are grown by just four oyster farms in Louisiana, Supan said — one in Plaquemines Parish and three on Grand Isle, which is home to a specialty oyster farming zone.

In restaurants, the grown triploids sell for about twice as much as regular oysters, and they’re sold one-by-one, not by the dozen.

One company that sells them is Caminada Bay Oyster Farm, run by Jules Melancon. Like other oyster farmers, he sells them to high-end restaurants, such as Peche Seafood Grill, Bourbon House and Seaworthy.

Melancon started growing triploids when his leased traditional oyster grounds stopped producing. He said he was drawn to the new kind of oyster farming because triploids take less time to grow large enough to eat — a year compared to two for other oysters.

Melancon said he gets about 70 cents for every triploid oyster, twice as much as he got for regular oysters.

“It’s a lot of work, but you can make a living,” Melancon said. “In the future I think they’re going to have more and more people doing what I’m doing.”

Won’t overtake traditional oystering

The oysters could theoretically be harvested and sold by more farmers, but Supan says there are several obstacles: the cost of the seed, the work to grow them and the risk that they will be poached by competing fisherman.

That’s why Supan expects triploids to supplement traditional oyster cultivation rather than replace it.

But he said the triploid market — and the grant that supports their continued development — is a premium alternative to the oysters sold by the sack during the colder months of the year.

And “sea farming concepts” learned from aquaculture, including off-bottom oyster development, could be applied to the state’s plan to protect and rebuild the coast, Supan said.

The state plans to use massive river diversions to pour sediment and freshwater into eroding wetlands. That could kill oysters by compromising the delicate balance of water and salt in which they thrive.

But the state could help oystermen prepare for freshwater diversions and the changes they’ll cause in water salinity.

According to Supan, oyster farms could be put in “the right place” if diversion projects are built to carefully measure how much freshwater is introduced to the brackish bays offshore.

“It takes progressive thinking,” Supan said.

In the meantime, Supan said his researchers are trying to figure out how to make triploids more affordable, and more marketable, to a wider array of farmers.

“We’re crunching numbers,” he said. “We’re still not there yet.”