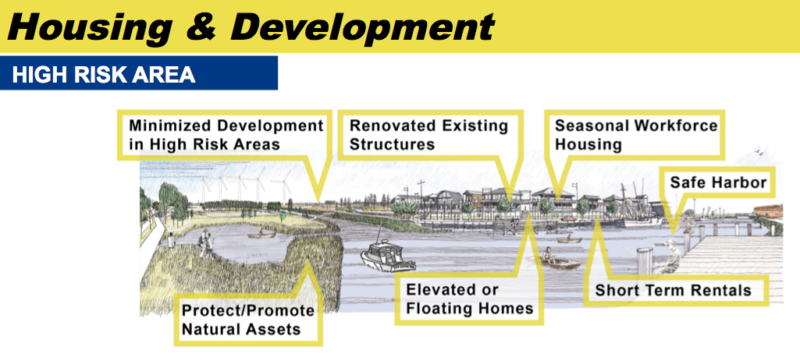

An illustration distributed by a state-led planning effort shows a version of Slidell’s future, with improved evacuation routes and elevated homes rather than ones sitting at ground level along Lake Pontchartrain.

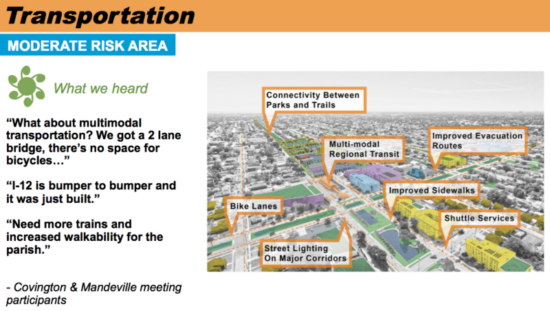

Around the bedroom community of Covington, drawings suggest more east-west highways, expanded bus routes and high-density housing.

The illustrations show how these communities, along with those in five other parishes in southern Louisiana, could be re-imagined to deal with land loss, intense rainstorms and hurricanes — all part of Louisiana’s likely future.

The mockups are the product of a series of meetings held by LA SAFE, a joint initiative of the state Office of Community Development and the Foundation for Louisiana to help parish residents plan for the future of their communities.

In high-risk areas — those likely to experience catastrophic flooding in future storms — the overarching theme is to replace high-density development with water-friendly recreational and commercial uses. Lower-risk, inland areas should plan for population growth.

“In high-risk areas, we’re trying to plan for declines in permanent resident population, while attempting to capitalize on potential economic value through activities promoting access to water and nature,” Mathew Sanders, director of LA SAFE, said.

“In moderate-risk communities,” he said, “we’re trying to promote fortification.”

“In high-risk areas, we’re trying to plan for declines in permanent resident population … In moderate-risk communities, we’re trying to promote fortification.”—Mathew Sanders, LA SAFE

The plans are meant to complement the state’s predictions that about 4,600 homes in St. Tammany Parish may have to be elevated due to flooding from land loss and climate change. Another 900 may have to be bought out.

Statewide, the state predicts that about 26,000 buildings may have to be flood-proofed, elevated or bought out.

Those predictions are part of the latest version of the Louisiana Coastal Master Plan, a blueprint to rebuild the coast and protect some of what’s left.

Most of the Master Plan relies on pipelines, massive river diversions, levees and floodwalls to protect and rebuild the coast. It also calls for roughly $6 billion in “nonstructural” projects such as elevating, flood-proofing or buying out homes.

The LA SAFE process is more wide-ranging, more conceptual and more uncertain.

Raising existing buildings, flood-proofing them or buying properties is “not enough,” said Liz Williams, coastal community resilience director with the Foundation for Louisiana and a member of the LA SAFE team.*

“It’s not big enough,” she said. “It doesn’t think about our culture, our communities, our social fabric or our economy.”

‘A more holistic view of planning’

LA SAFE’s work comes as the forecast for coastal Louisiana has become grimmer due to new research on sea-level rise. The worst-case scenario for sea-level rise in the 2012 Coastal Master Plan is now the best-case.

The new plan, released in January, says even if all the restoration projects work as they should, 2,800 square miles of the state’s coast could still erode in the coming decades.

“Louisiana faces hard decisions,” wrote researchers for the RAND Corporation, a partner in developing the Master Plan, in an April 2016 report. “There is no single solution that will solve every challenge facing the coast.”

The state may have to spend $1.6 billion in St. Tammany Parish to shore up homes and businesses or buy them out — the most of any parish.

The LA SAFE projections don’t include any specific plans for that work.

“What we’re trying to do is encourage behavioral change by using flood risk as a barometer.”—Mathew Sanders, LA SAFE

So while community members envision a future with raised buildings in high-risk areas and high-density development in low-risk areas, the mockups created by LA SAFE do not say which homes would need to be bought out or raised.

In a “Frequently asked questions” section on the LA SAFE’s website, one question is, “Are you telling people to move?”

The answer: “No. By no means is the State of Louisiana planning on going into communities and telling people to move. This is an effort that is rooted in community [driven] initiatives. Decisions about the future will be made by those communities based on current and future risks.”

Sanders said LA SAFE’s models for these communities are meant to supplement the Master Plan.

“This is an attempt to take a more holistic view at planning,” he said. “Community development is more than elevating a house, or buying out someone who might be at particular risk. It’s other economic drivers that make up a livable community in a functional place.”

LA SAFE expects a significant increase in population in St. Tammany Parish, Sanders said. As the Master Plan notes, the population there grew 22 percent from 2000 to 2010.

According to the Master Plan, 41 percent of St. Tammany lies within the 100-year floodplain, the area projected to be flooded during a storm that has a 1 percent chance of occurring in any year.

Sanders said the mockups do expect portions of Slidell, Eden Isle and some areas along the lakefront to be high-risk zones, with 14 feet or more of flooding during a 100-year event.

But that’s “an extremely limited geographic area,” he said.

Other areas, including parts of Mandeville, would be subject to moderate flood risk — 3 to 14 feet of flooding from a 100-year storm.

Most of the parish, everything north of Interstate 12, is defined as low risk.

For each of those areas, LA SAFE asked residents to plan for five categories:

- Culture and recreation

- Education, economy and jobs

- Transportation

- Stormwater management and green space

- Housing and development

In high-risk areas, LA SAFE proposals for St. Tammany include more recreational pathways, floating homes and businesses, commercial fishing and water taxis.

Moderate-risk areas call for community gardens, bioswales and parks designed to hold stormwater. Residents have also proposed elevated roadways, ecotourism attractions and ways to improve river quality and access for recreation.

Proposals for low-risk areas include farmers and seafood markets, paved bike paths, more affordable housing, a local tram system, high-density zoning and even a new commuter rail.

“What we’re trying to do is encourage behavioral change by using flood risk as a barometer,” Sanders said. “We need to start designing not around current conditions, but around a future condition.”

Money for plans, but not to implement them

LA SAFE’s planning process is funded by a $40 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Jefferson, Lafourche, Plaquemines, St. John the Baptist and Terrebonne parishes are also participating. They were chosen because they were most impacted by Hurricane Isaac in 2012.

So far, nearly 1,500 residents have participated in dozens of LA SAFE meetings.

In St. Tammany, reactions have been mixed. A survey done by LA SAFE showed the majority of residents at a meeting in late July approved the general ideas presented for cities such as Slidell, Covington and Mandeville.

But LeAnn Pinniger Magee, chairwoman of the Abita Committee for Energy Sustainability, said the planning process may not be that helpful because most people who participated in the meetings don’t know how to address the complex problems associated with higher flood risk.

“It’s easy to accept that which an organization has outlined for you,” Magee said. “It’s hard to think about the missing pieces.”

One of those missing pieces is funding. The $40 million planning grant is paltry compared to the $3.6 billion in infrastructure that could be lost due to land loss if the state doesn’t take action to protect and restore the coast.

$40MTo plan for higher flooding in six parishes and fund pilot projects$92BEstimated cost of state’s plan to rebuild and protect the coast

LA SAFE plans to fund one pilot project in each parish. Otherwise, the documents created by the planning grant will serve as a priority list for future projects.

“Ultimately, there are some funding decisions we are going to have to make,” Sanders said.

That’s also true of the Master Plan, which is being developed and implemented by a separate state agency, the Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority.

View the detailed mock-ups for high, medium, and low-risk areas of St. Tammany Parish

In 2012, researchers said $50 billion would be needed to undertake the 50-year, last-ditch effort to save Louisiana’s coast. A more recent study by Tulane University, however, put that price tag closer to $92 billion.

The state doesn’t have most of the money it needs for all those projects.

But even if LA SAFE never comes up with the money for further projects, Sanders said the mock-ups could provide blueprints for future parish, state and federal government budgeting.

Through the meetings and the proposals, Sanders said, the LA SAFE team is exploring whether these communities can be re-imagined to deal with land loss and increased flooding. “We’re testing a concept.”

*Correction: Liz Williams’ title was incorrect in the original version of this story. (Aug. 9, 2017)