The Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office runs a lucrative program hiring out deputies for private security work frequently at far higher pay than their commissioned duties – but it’s not just the deputies who are bringing in a tidy sum. The program provides Sheriff Marlin Gusman with a regular supply of discretionary money.

For every hour Gusman’s deputies work on a moonlighting shift, they pay $1 into what’s called the Sheriff’s Detail Fund. In addition to writing thousands of dollars in checks to “cash” out of this account, Gusman has used this fund to buy alcohol for parties and gifts for his employees, according to records obtained under the state’s Public Records Act. The state Attorney General has said such spending is an illegal use of public money.

Aside from that discretionary fund, the overall sheriff’s program of outside paid details is remarkably similar in structure to the one run by the New Orleans Police Department, which the U.S. Department of Justice excoriated as an “aorta of corruption” in the department.

The Lens investigation found that:

- deputies frequently earn a higher hourly rate at their moonlighting jobs than their regular work as prison guards, raising questions about which duty commands their loyalty.

- three deputies out of 14 sampled in one month were paid for working details at the same time they were on the clock and being paid with taxpayer money, according to Sheriff’s Office records.

- it’s difficult to fully track all deputies’ details through public records because the Sheriff’s Office destroys electronic databases used to record assignments, keeping only paper copies, an attorney for the sheriff said. That’s in spite of a state law that requires public agencies to keep all records it creates for at least three years.

- low-ranking deputies sometimes are in charge of making assignments for the moonlighting work, an arrangement that lets them dole out lucrative assignments to their regular-duty superiors, putting the Sheriff’s Office chain of command in jeopardy.

- a City Council member overseeing criminal-justice issues was not aware of the detail fund, even though the city provides Gusman with money to cover his expenses associated with running the jail.

- Gusman’s paid detail program exhibits many of the other flaws that were singled out by the Department of Justice as contributing to corruption within the city’s police department.

Perhaps because Gusman controls the city’s jail, and his deputies are responsible for controlling inmates, rather than interacting with the public, there is less interest in the effects of Gusman’s paid detail policies than in those at the police department. But deputies have responsibilities to ensure the safety of inmates at the jail, including: assessing inmates for signs of mental health problems, preventing physical abuse, coordinating medical care with medical staff including doling out medications, properly reporting use of force incidents, investigating problems, and maintaining suicide watch.

Gusman’s publicist Marc Ehrhardt wrote in an email response to questions for this story that the detail system is undergoing a “comprehensive policy review” as part of an annual policy review at the Sheriff’s Office. Gusman “will implement policy revisions as part of this annual process around the first of the year,” Ehrhardt wrote.

Gusman began this review in September, Ehrhardt wrote. That’s not long after The Lens began asking questions and requesting records about paid details at his office.

Deputies may earn more working paid details than they do for the sheriff, but Ehrhardt wrote that detail payments do not include health insurance, pension contributions, life insurance and deferred compensation. Ehrhardt also wrote that deputies have to punch in when arriving for their shift and leaving for the day, verifying their identity with a fingerprint machine. Still, when it comes to employees working paid details at the same time they were on the clock, Gusman is investigating each instance, Ehrhardt wrote.

“However, in each case mentioned below, it does not appear that these deputies participated in these activities with criminal intent,” Ehrhardt wrote. “If the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office determines that these deputies violated OPSO policy or the law, then the OPSO will take appropriate disciplinary action immediately.”

Gusman’s office is also allowed to toss out electronic versions of detail records as long as a paper copy is kept, under his attorney’s interpretation of state public records law, Ehrhardt wrote.

The sheriff also reimbursed the detail fund for the alcohol purchase out of his own pocket “in an abundance of caution,” Ehrhardt wrote, though he did not say when that happened.

The Lens’ findings concern some public watchdogs.

“You’ve identified some deputies that were working on the clock for the Sheriff’s Office at the same time as working a private detail,” said Rafael Goyeneche, president of the nonprofit Metropolitan Crime Commission. “That is a problem, and the Sheriff’s Office needs to conduct an internal investigation to determine if the information is in fact correct, and if so then it needs to be referred to the District Attorney’s Office because it could be payroll fraud.

“There are lessons to be learned from what has been exposed with respect to the NOPD and I think the same concerns and principles that apply to the NOPD apply to any law-enforcement agency that allows their employees to work extra-curricular details,” Goyeneche said.

The paid details may be causing other issues, said Marjorie Esman, executive director of the ACLU of Louisiana.

“We know that paid details are a problem at the NOPD, and it appears that they are the same problem at the Sheriff’s Office,” she said. “We have the chain of command being disrupted, we have people being paid off the clock while they’re on the clock, which is not only a misuse of public funds but also may partially explain why the jail is so understaffed and dangerous.

“There is a real problem, generally, with the Sheriff’s Office not being particularly transparent, and if they are destroying public records in violation of state law around this issue, it undermines the credibility of the office with respect to other records,” Esman said.

Fewer sheriff’s deputies work paid details than New Orleans police officers, placing more power in the hands of detail coordinators at Gusman’s office — 165 of Gusman’s 700 employees, or about 25 percent, work details, according to budget documents. That compares with about 70 percent of the city’s 1350-strong police force working details between 2009 and 2010, according to the Department of Justice.

On average, records show deputies worked 7,939 hours of details a month in March, April and May of this year. At that rate, deputies work nearly 100,000 hours a year – providing nearly $100,000 to Gusman’s detail fund.

Many of the same deputies worked several details, but between 40 and 60 deputies worked paid details on any given day during that period.

Using conservative estimates of the lowest rate of outside pay, moonlighting jobs paid at least $2 million a year in extra income to Gusman’s deputies.

LITTLE OVERSIGHT OF DISCRETIONARY SPENDING

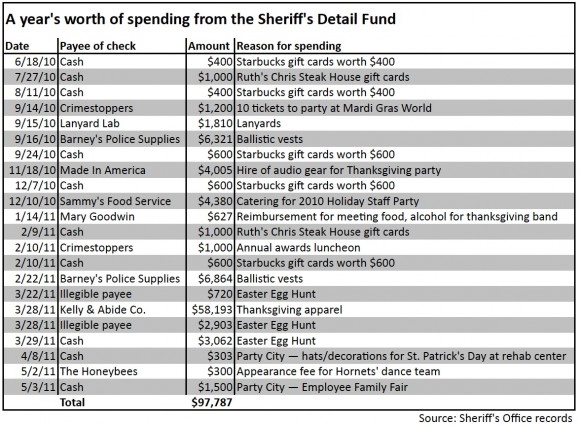

Deputies pay a dollar an hour for every hour they work on paid details to the detail fund, wrote Craig Frosch, an attorney for Gusman at the firm Usry, Weeks & Matthews, in a letter to The Lens. Records show that the fund contained monthly balances of between $62,000 and $120,000 between June 2010 and June 2011.

The detail fund is not directly referenced in an annual audit submitted by law each year to the State Legislative Auditor, although a “Detail Account” does show up in Gusman’s 7,000-page check register, as part of Gusman’s general fund. Gusman’s auditors at the firm of Postlethwaite and Netterville wrote that the detail fund is audited as part of the sheriff’s general fund.

Deputies said Gusman has told them that the detail fund pays for bulletproof vests and radios. And in fact, $12,000 was spent on bulletproof vests over the 12 months The Lens examined.

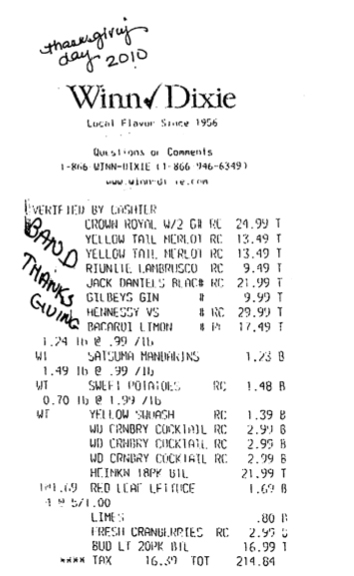

But records show Gusman also signed almost $10,000 in checks to cash from the fund, spent nearly $60,000 at an apparel firm, spent $1,200 on a table for 10 of his staff at a Crimestoppers party at Blaine Kern’s Mardi Gras World, spent $300 for the Hornets cheerleading team, The Honeybees, to appear at a function, and spent $100 on alcohol for a band at his annual Thanksgiving dinner, including Jack Daniel’s whisky, Hennessy cognac, and Bacardi rum.

Attorney General Buddy Caldwell has said previously in unrelated opinions that the use of public funds for parties and celebratory functions is illegal.

Gusman reimbursed the money spent on alcohol from his own funds in “an abundance of caution,” Ehrhardt wrote, though he didn’t say when the repayment occurred.

Records show the checks to cash were used to buy Starbucks gift cards for “spiritual guest speakers as a token of appreciation,” multiple $100 Ruth’s Chris Steak House gift cards to congratulate employees of the month, coloring books and Walmart gift cards for Gusman’s Easter egg hunt, and hats and decorations for a St. Patrick’s Day party at a rehabilitation center.

Caldwell has also written that using public dollars to purchase restaurant gift certificates for employee of the month awards is illegal.

Gusman provided a letter from his auditing firm, Postelthwaite and Netterville, which said “employee award programs are allowed and based on our understanding of your program, it would be allowable.”

But Goyeneche is concerned.

“I clearly believe that the detail funds are public funds, and as such, if they are public funds, then they cannot be used to purchase alcohol or award gift cards to employees,” Goyeneche said. “And I understand that you’re trying to create a good work environment for your employees, but the law is the law, and you can’t do that with public funds.

“As far as purchasing alcohol, I’m told the alcohol is for some musicians that donate their time to the sheriff’s Thanksgiving and Christmas dinners, which are worthwhile and noble causes, but you can’t use public funds to purchase alcohol,” Goyeneche said.

Gusman paid $58,193 to apparel firm Kelley and Abide on March 28, 2011, for things such as customized T-shirts with Christmas logos on them, Santa hats, knitted beanie hats, aprons with a “Sheriff Thanksgiving Logo,” tote bags with the sheriff’s logo on them, embroidered golf shirts, and magnifying glasses.

Gusman also spent nearly $10,000 from the detail fund to buy 6,000 sets of Carnival-style beads with sheriff’s cars medallions on them. His deputies sometimes hand out the beads to members of the public when they are working details.

DOUBLE-DIPPING DEPUTIES

The Lens requested timesheets for March 2011 for a random selection of 14 deputies working details. Of those, three took taxpayer dollars working an official Sheriff’s Office shift at the same time they claimed money for paid details.

•On Thursday, March 10, records show Deputy John Sens worked a paid detail between noon and 8 p.m. for Woodward Construction, patrolling the perimeter of Gusman’s new kitchen and warehouse facility for his planned new jail. But Sens’ timesheet at Gusman’s office also showed him clocking in for a 10-hour shift working in Gusman’s contracting department between 7 a.m. and 5 p.m. on that day.

Gusman’s office is investigating, Ehrhardt wrote, expecting to conclude its investigation this week.

•On Friday, March 25, records show Deputy Harlon Martinez worked two paid details — one at the Walgreens at 4400 South Claiborne Ave. between 8 a.m. and 2 p.m. and another at the Walgreens at 5501 Crowder Blvd. from 7 p.m. to 11 p.m. But Martinez’s timesheet at Gusman’s office also showed him clocking in for a 12-hour shift at the Conchetta facility on Tulane Avenue between 6:26 a.m. and 6:30 p.m.

Gusman’s office responded, saying Martinez punched in for his assigned shift, and that he also made handwritten notes into internal jail logs. Ehrhardt also wrote that no deputies are working a detail at the Walgreens on South Claiborne, although Gusman’s own records list Martinez as having worked that detail twice more that month, and another deputy is listed as having worked the detail too. Ehrhardt did not respond to a follow-up question on this point.

•On Thursday, March 3, records show Deputy Bucky Phillips worked a paid detail between 6 p.m. and 10 p.m. for Hotard on Convention Center Blvd. But Phillips’ timesheet at Gusman’s office also showed him working a 12-hour shift between 5:57 a.m. and 6:25 p.m.

Gusman’s office is investigating, Ehrhardt wrote, expecting to conclude its investigation this week.

It’s difficult to easily track all the shifts through computer analysis because Frosch said Gusman doesn’t keep computerized records. Instead, Frosch said the office prints out the spreadsheets and then trashes the electronic database. State law requires public agencies to keep public records for at least three years, and the definition of a record includes any data kept in a computer.

Ehrhardt and Frosch interpret the public records law differently, saying the law only requires agencies to keep a paper copy of the public record, not every copy.

“At the very least,” Ehrhardt wrote, “the point is arguable.”

In responding to The Lens’ public-records request, three days of paid detail records were simply missing, with Gusman unable to offer an explanation. Ehrhardt wrote that the office was “not aware of any missing records,” even though The Lens had already asked Frosch for the missing records and clarified the dates of the missing records with Ehrhardt.

In examining the New Orleans Police Department, the Department of Justice criticized a lack of centralized, organized recordkeeping for paid details, saying it creates an environment in which officers are able to bend the rules without getting caught.

A CASH BUSINESS

Gusman does not track how much money his deputies earn for working paid details, or for coordinating details, Frosch wrote. Deputies are also allowed to accept cash for working paid details, Frosch wrote. Deputies also are allowed to perform paid details without handing out receipts or any particular paperwork, Frosch wrote.

Ehrhardt wrote that it’s up to the deputies to handle their own financial matters.

“Because deputies working details are engaged in a transaction with a private individual or company, the deputy is responsible for accounting for the funds that deputy receives, as part of their own annual tax returns and required financial documents,” Ehrhardt wrote.

Jefferson Parish resident Sandy Milliken wanted to arrange a motorcycle escort from St. Agnes church in Jefferson Parish to City Park for her son’s wedding reception this summer. She was told to call a sergeant with Gusman’s office, who told her to bring $100 in cash in two separate envelopes to give to two motorcycle deputies at the wedding.

“It made me feel kind of creepy,” Milliken said. “I watch the news quite a bit, and it just made me feel like maybe they were taking advantage of the public. I think there should be better accounting.”

Milliken was given no receipt or paperwork in exchange for the payments, although she did not ask for one, she said. And she said she was satisfied with the service performed by the deputies, apart from her discomfort over the method of payment.

DO GIVE UP YOUR DAY JOB

Of the 14 deputies whose timecards we scrutinized for the month of March, four appear to have earned more money working paid details than they earned working on the clock for Gusman.

•Phillips earned over $3,500 working paid details for Walgreens and Hotard, more than his $2,650 gross salary.

•Deputy Gerard Golden earned $3,000 working paid details for Walmart, more than his $2,775 gross salary.

•Special Operations Field Training Officer Ernest Newman earned at least $4,000 working paid details at branches of Walmart, barber shops, and daiquiri shops, more than his $2,900 gross salary.

•Court Security Lt. Craig Lawson earned at least $3,600 working paid details at branches of Walmart, and at Harrah’s Casino, more than his $2,900 gross salary.

Gusman’s deputies start on salaries of $9.50 an hour, Frosch wrote, compared to paid details, which vary from $30 an hour at Harrah’s Casino, $35 an hour at Walmart, and $40 an hour at Woodward Construction.

Ehrhardt wrote that the standard hourly rate for details is based on the overtime rate scale for Gusman’s office.

When the Department of Justice took aim at the details policy in the New Orleans Police Department, it said the quality of policing is undermined when officers can earn more money on their details than they do as officers, because they may feel greater allegiance to their detail employer than they do to the public.

SUPERVISORS WORKING FOR THEIR EMPLOYEES

The Lens requested the ranks of 16 random detail coordinators out of over 100 listed at Gusman’s office for the period we examined. We found that five coordinators were ranked as mere deputies, the lowest rank, meaning they’re deciding outside assignments of either their peers or people who outrank them.

“This is something that has been banned in the NOPD and many other law enforcement agencies because it turns the chain of command upside down,” Goyeneche said. “This is an issue that needs to be looked at by the Sheriff’s Office to make sure that there aren’t any instances of that happening.”

One example of such a disruption in the chain of command is Maj. Bonita Pittman, whose day job is to run the Templeman Five jail, where Gusman houses immigration inmates, women, and some federal prisoners.

Records show Pittman worked 22 hours of paid details for Woodward Construction in March, patrolling the perimeter of Gusman’s new kitchen and warehouse facility for his new jail. Records show the security detail for the Woodward site is run by Deputy Robert Gates, who works in “security,” according to Gusman’s official records. While Gates is not a direct report to Pittman, she was still beholden to a ranked inferior for the lucrative $40-an-hour detail, which earned her an extra $880 in March.

Ehrhardt wrote that “multiple detail coordinators” work the Woodward detail, but records for the period only list Gates as the coordinator, and Ehrhardt did not respond to follow-up questions on this point.

The Department of Justice report about the police department spelled out why such a disruption in the chain of command could be bad for a public safety agency.

“Having lower ranked officers acting as coordinators puts supervisory officers who want to make extra income in a situation where they answer to a lower ranked officer,” the report said. “This naturally affects the ability or willingness of the supervisor to question the performance of, or to discipline, an officer who is responsible for the supervisor’s additional income. This also leads to the appearance of, if not the reality of, favoritism.”

SPENDING WITH ONE HAND WHILE ASKING WITH THE OTHER

Though it’s a small amount of money in the scale of Gusman’s $175 million budget, the detail fund is nonetheless a source of loose cash for the sheriff, who regularly pleads for more money from the City Council.

Councilwoman Susan Guidry, who is co-chairwoman of the Criminal Justice Committee, had not heard of the detail fund when asked about it by a reporter. She declined to comment further.

Guidry and her colleagues frequently seek more information on the sheriff’s budget.

OTHER PRACTICES THAT COULD SPAWN CORRUPTION

Other aspects of Gusman’s paid detail program are reminiscent of criticisms raised by the Department of Justice in its report on paid details at the police department:

•Gusman’s deputies work long hours on details, which could lead to potentially dangerous fatigue and endanger inmates in Gusman’s jails.

•Gusman’s deputies appear to work at outlets selling alcoholic beverages, despite a rule saying they should not, without the sheriff’s approval.

•Gusman’s paid detail practices raise the appearance of favoritism and conflict of interest.

Gusman’s paid detail policy is actually more prone to cause his deputies to become fatigued than the NOPD policy slammed by the Department of Justice.

The police department policy in place at the time of the federal review allowed officers to work an additional 28 hours per week, with little oversight to ensure that the cap is observed. Meanwhile, Gusman’s policy allows deputies to work up to 32 hours a week on top of their regular jobs.

“If you’re working 48 hours a week for the sheriff’s office and then another 32 hours, that’s 80 hours, and no one can maintain that indefinitely,” Goyeneche said. “Is that good public policy? Obviously the police department believes that optimally, 64 is a better number. I would be surprised if 80 hours was the national standard.”

In 2009, the Department of Justice criticized conditions at Gusman’s jail facilities in a damning letter, and Department of Justice attorneys have continued to insist that a court-enforced order over jail conditions is imminent.

There have been 13 deaths in Gusman’s jail since the report was written, including a man who died recently after eating half a roll of toilet paper and suffocating on it, while he was on suicide watch.

“Being sleep-deprived, especially chronically so, can contribute to an officer making dangerous tactical errors; missing potential evidence; taking investigatory short cuts; writing incomplete reports; providing inaccurate testimony; and acting unprofessionally towards residents,” the Department of Justice report about details at the NOPD said.

Two sheriff’s deputies who have worked at the Templeman Five facility told The Lens that supervisors would frequently take naps while on duty, to make up for the hours they had been working on details. The Lens is not identifying the deputies because they are concerned about potential employment repercussions for speaking out.

Ehrhardt wrote that deputies are required to have a minimum of six hours of downtime between the end of a detail assignment and the beginning of a scheduled shift. There are also surveillance cameras at sheriff’s facilities, and deputies who fall asleep are disciplined, Ehrhardt wrote.

Gusman’s paid detail policy forbids working at alcoholic beverage outlets unless Gusman gives permission. But in the handful of detail records obtained by The Lens, there are several instances of deputies working at daiquiri shops.

Ehrhardt wrote that Gusman has not approved a new request for deputy details at alcohol beverage outlets since taking office in 2004, but that a few alcoholic beverage outlet details were grandfathered in.

Gusman’s choice of Deputy Gates to coordinate the Woodward Construction security detail for his new jail kitchen and warehouse facility raises the appearance of a conflict of interest, since marriage records show that Gates is the son-in-law of Gusman’s former top aide, the late Chief Deputy Bill Short.

Short, who died in October, donated over $10,000 to Gusman’s political campaigns since 2005, state campaign records show. He also helped choose the selection of a construction manager at the kitchen and warehouse facility in 2008.

Ehrhardt wrote that deputies asked to fulfill detail assignments are asked to do so “because they have the capabilities to do the job requested of them.”

In another instance, Deputy Sens works as Gusman’s director of purchasing, and shepherded the approval of Woodward Construction for the contract on the kitchen and warehouse facility through to completion. His signature and name appears on many letters to and from Woodward at various stages of the bid process.

Now Sens is paid by Woodward for working a security detail at the site. Records show Sens earned $700 in March.

Ehrhardt responded to this by writing that Gusman’s project manager, Ozanne Construction Co., “directs all interactions between the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office and contractors working on various projects. The project manager also develops all bid specifications and packages distributed to the public for bid.”

Woodward is not happy with the amount it’s paying for extra security – at a site within the sheriff’s control.

Woodward filed a suit against Gusman in Civil District Court in July for alleged breach of contract after Gusman’s staff told the company that the bill for security at the facility would cost about $33,000. The lawsuit says the company has been billed more than $300,000 for the work and expect that amount to double by the end of the project. The sheriff’s office rebutted Woodward’s allegation in documents filed with the court and the case remains open.

Woodward Construction did not respond to a request for comment.

The head of the Bureau of Governmental Research, which published a report on best practices for police details earlier this year, said likely reforms at the NOPD need to also be enacted at Gusman’s office.

“After the justice department issued its report, Chief Serpas proposed a plan to reform the NOPD’s detail policies and procedures, and one of the criticisms that is sometimes heard is that it would just shift the detail work to the sheriff’s department,” Janet Howard said. “ And clearly, the reforms should extend to all the law enforcement groups engaged in the practice in the jurisdiction.

“And that’s not an argument for delay with proceeding with the NOPD reforms, but the community needs to stay focused on a comprehensive approach.”