By Ariella Cohen, The Lens staff writer |

The accidents unfold with eerie similarity: an unexpected explosion, a stubborn blaze, workers coughing and rubbing damaged eyes, a thick, ash-colored cloud of toxins racing away from the burning refinery.

On July 19, 2009, when a refinery in Corpus Christi, Texas, lit up, a worker was critically hurt and the fire burned for two days. On Nov. 24, 1987, an explosion at an ExxonMobil refinery in Torrance, Calif., shot a fireball 1,500 feet into the air, blasted the windows out of nearby houses and generated allegations of broken eardrums, back pain and lung damage.

The common denominator in both explosions was a toxic chemical many Louisiana residents have never heard of, though more than 3.7 million people across the state are at risk if a similar explosion happens here, according to company filings submitted to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Hydrofluoric acid is a chemical catalyst known for its power to etch glass, as well as its extreme toxicity. Equally distinctive: its ability to move across long distances in a potent chemical cloud. While historically used in many industrial processes, the acid’s highest-volume consumers today in the United States are oil refineries that use it to make high-octane gasoline.

Exposure to hydrofluoric acid fumes causes lung congestion and severe burns of the eyes, skin and digestive tract. It corrodes bones. Extreme exposure has caused fatal lung failures. Experiments in 1986 showed that the acid compound, commonly known as HF, can be lethal almost 2 miles from the point of release, and cause sickness almost 5 miles away.

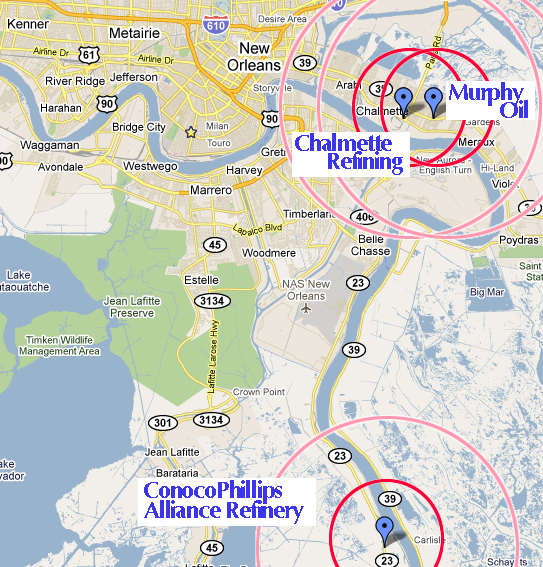

Despite this capacity for harm – and despite the availability of a safer alternative that is used in half of the nation’s refineries that do such work – 50 of the nation’s 148 oil producing facilities continue to rely on the lethal compound, five of them in Louisiana, and three of those in the New Orleans area.

The Louisiana refineries are:

- Chalmette Refining in Chalmette

- ConocoPhillips Alliance in Belle Chasse

- Marathon Petroleum in Garyville

- Murphy Oil in Meraux

- Placid Refinery in Port Allen

Only Texas, with 10 refineries that use hydrofluoric acid, has more of the toxin within its state borders. Elsewhere, refineries and other industries that could use hydrofluoric acid have turned to alternatives, chiefly sulfuric acid, which is used by more than half of them, and a modified HF that was developed by ExxonMobil in the 1990s, in response to safety concerns. Modified HF is now used in 10 refineries across the country, none of them in Louisiana. These alternative catalysts don’t race across the landscape in ways comparable to HF when used in the concentrations required by the oil industry. And because these chemicals aren’t as easily spread, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security doesn’t consider them to be as high a security risk as unmodified HF, a federal registry of chemical threats show.

New facilities can also rely on solid acid catalysts, a material that does not create a toxic cloud if released, though no companies have made the switch to the newly developed technology, said Paul Orum, a chemical safety consultant who works with public-interest groups.

“They are invested in the technology they have, and it would cost money to convert,” he said.

Industry lobbyists have said a switch would be too expensive. They estimate the cost of switching from HF to one of the alternatives to be somewhere between $50 million and $150 million per refinery. For comparison’s sake, ExxonMobil alone reported profits of $9 billion in the fourth-quarter of 2010.

A recent spate of refinery equipment breakdowns, fires and safety violations has heightened concern nationwide. Over the past five years, authorities have cited 30 of the 50 refineries using HF for willful, serious or repeat violations of federal rules designed to prevent fires, explosions and chemical releases, according to data from the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration. The data was analyzed in a joint investigation by The Lens, the Center for Public Integrity, a non-profit investigative newsroom based in Washington, D.C., and ABC News.

Among the violators, ExxonMobil’s St. Bernard Parish refinery, Chalmette Refining stands out for its long list of safety violations. Since May of 2009, the facility on West St. Bernard Highway has racked up 16 serious violations totaling $27,750 in penalties, OSHA records show. Several of the violations specify safety hazards in the unit of the refinery where the company stores the 620,000 pounds of hydrofluoric acid.

Twice in the past five years, the toxic chemical has escaped from the refinery in accidents, Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality records compiled by the Louisiana Bucket Brigade show. In both instances, the releases were contained and no serious damages were reported, despite the sizeable release of 3,357 pounds. If the releases had been larger, up to a million people could have been injured, according to the worst-case scenario documents that the company is required to submit to the federal Environmental Protection Agency.

“The community has been fortunate,” the Bucket Brigade’s founding director Anne Rolfes said. “But it’s very much like the BP oil spill: You can be relaxed about a threat until something terrible happens.”

The industry minimizes the risks of HF, saying it has adequate safeguards in place and that the chances of a catastrophic accident at any one refinery are slim. All five Louisiana refineries declined to comment for this story, referring all questions to the National Petrochemical & Refiners Association, in Washington, DC. The lobbying group declined to speak to The Lens, but in an interview with the Center for Public Integrity and ABC News, the association’s president, Charles Drevna, said that the industry has never released HF in a way that “impacted” communities. “We’ve controlled [releases],” he said.

ExxonMobil owns Chalmette Refining as well as a larger refinery in Baton Rouge, and the Torrance Refinery in California where HF escaped in the 1987 blaze. Of the three, Chalmette is the only one where hydrofluoric acid is still used. When asked why the multinational giant has not switched to a safer alternative in Chalmette, company spokesman Kevin Allexon declined to comment. “These are industry issues and not ExxonMobil-specific issues,” he said. On the website of the Torrance Refinery, the company touts its introduction of modified HF as a change to make facility operations “safer for workers and the community.”

Chronic disregard for safety

On Sept. 6, 2010, thousands of people from Chalmette Vista to New Orleans’ Lower 9th Ward woke up to find their world coated in a mysterious white dust. The fine powder covered lawns and trees, houses and cars, giving the odd appearance that snowfall had interrupted the balmy Louisiana autumn.

Many in St. Bernard assumed that the chemical dusting, like the sulfurous odors that occasionally wash over the parish, came from the refineries. Beyond that, no one knew exactly what the dust was, or what it would do to their lungs.

“I was concerned and I think everyone was,” St. Bernard Parish Council Member-at-large Wayne Landry recently recalled. “When you don’t know what’s going on, you don’t know what’s in the air you are breathing in, you are concerned.”

Within hours of the accidental release, Chalmette Refining issued a statement telling the public that the powder was a material called spent catalyst that had been released during a power outage at the refinery. It was not hazardous and could be safely washed off, state officials and ExxonMobil spokesman Will Hinson assured worried residents. Yet when people asked for a list of chemicals in the material that had blanketed their communities, Hinson said he did not know. The company initially reported that one ton of the catalyst, which the Environmental Protection Agency classifies as a hazardous waste but not an extremely hazardous substance, had been released. Later, ExxonMobil reported that the actual release totaled 19 tons. In the months since, civilians have filed lawsuits against the company, alleging the dust harmed them and their children.

Meanwhile, a Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality investigation has not yet determined whether the company will be penalized for the accident, though the agency’s preliminary findings report that it released two chemicals classified by the federal government as “extremely hazardous,” along with the less toxic spent catalyst. Any penalties levied would be subject to challenges from the company before any final settlement is reached, agency spokeswoman Jean Kelly said. Parish officials say there is nothing more to be done now that the dust is gone.

A look at Chalmette Refining’s violation history reveals patterns of disregarded safety precautions and lax enforcement. In the past two years, OSHA downgraded all 17 penalties against the refinery, informally settling with ExxonMobil and collecting fewer dollars in fines with each downgrade.

Alarmingly, the bulk of the violations were recorded in areas of the refinery reserved for the processing of hydrofluoric acid and other toxins deemed dangerous enough by both the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and the EPA to require risk-management plans.

In September of 2009, for instance, OSHA imposed a $2,000 penalty for the refinery’s failure to provide “safe access” to the emergency fire-water pump in the alkylation unit, where hydrofluoric acid is used as a catalyst. The fire-water pump is the first defense available to refinery workers in the case of a spill or explosion. The refinery settled the issue with OSHA in January 2010, paying a $1,500 penalty. Another violation pointed to hazardous conditions on work platforms adjacent to the HF alkylation unit. Still another penalized the company for failing to provide safety equipment next to the HF unit.

“Where employees were exposed to injurious corrosive materials, suitable facilities for quick drenching or flushing of the eyes and body were not provided within the work area for immediate emergency use,” an OSHA inspector wrote.

OSHA inspectors also found in 2009 that the refinery was not adequately maintaining and inspecting its equipment.

“The frequency of inspections and tests of process equipment to maintain its mechanical integrity, was not consistent with applicable manufacturers’ recommendations and good engineering practices,” an inspector wrote. In this case too, the refinery ended up negotiating a reduction in the penalty, from an initial fine of $7,000 to a $5,250 settlement.

Around the same time, OSHA cited the refinery for a long-term failure to correct serious safety violations in its hydrocracker unit, where workers handle hydrogen and other extremely volatile chemicals. The hazards were first observed in 2003 and then in 2009.

“This exposed employees to fire, explosion, and respiratory hazards,” an OSHA inspector wrote in November 2009. The inspector also noted the “possibility of losing containment” of hydrogen “a very explosive and flammable gas,” and hydrogen sulfide, “an extremely toxic gas.”

The warning was prescient. Less than a year later, a contract worker at the refinery, Gregory Starkey, 33, died while repairing a pipe leaking hydrogen sulfide gas. The pipe had been broken for two weeks before Starkey’s death, company reports show.

In January 2010, the violation was settled with the refinery paying $5,250, a downgrade from the initial $7,000 penalty.

Residents say the record of lax enforcement illustrates the challenge they face in pushing area refineries to be more accountable to the community members and to make changes, such as switching to modified HF.

“Often times when a resident approaches a local official about a routine code compliance issue involving the refineries, they will just say, ‘Oh, but that is a refinery,’ like we should just expect codes to be violated. It is a non-response,” Chalmette resident Suzanne Kneale said, adding that she recalls instances in which homeowners succeeded in filing insurance claims against a refinery for damaging a house with machine vibration before the local government even acknowledged the refinery was in violation of the zoning code.

Recently, some of Kneale’s neighbors, members of a St. Bernard group called Concerned Citizens Around Murphy, won a victory against Murphy Oil USA in federal court, successfully charging that the company had released more chemicals than allowed from its Meraux plant. In penance for its violations of the federal Clean Air Act, U.S. District Judge Sarah Vance signed off on a consent decree earlier this month ordering the refinery to pay $1.25 million in civil penalties, invest more than $142 million in new equipment to reduce future pollution and spend at least $1.5 million on environmental projects statewide. Yet even with that legal victory behind them, Kneale doesn’t think residents have much leverage when it comes to getting refineries to switch to modified HF.

“If there was an alternative these refineries could use, we would prefer they use it,” she said. “But how can you sue for an alternative when HF is allowed under the current regulations?”

Before Hurricane Katrina, Chalmette Refining stood within three miles of twenty schools, two hospitals, and six retirement communities. The steep population loss since the storm means not all those facilities are back in operation, but a number have reopened, including two public schools within a two-mile radius of the refinery.

“We are not asking them to shut down the industry,” she said. “We just want them to make the industry comply with regulations that provide for health and safety.”

In the case of HF, federal agencies and the state Department of Environmental Quality regulate its use with permits and safety requirements. With more than 10,000 sites under its watch, the agency typically inspect sites just once a year, though inspectors will return if incidents occur or inspectors observe a need, said Chris Piehler, administrator of the inspection division. He said that while the agency would prefer that industry use the least noxious chemicals possible, it is not within DEQ’s mandate to force companies to use safer materials, as long as all materials being used are legal.

“We reduce or minimize the release of any pollutant whether it is HF or some safer ingredient,” Piehler said.

Like Drevna from the National Petrochemical & Refiners Association, he pointed out there had yet to be a major release of HF in Louisiana.

St. Bernard Parish officials have a similar view of the limits of their power.

“These refineries are basically big time bombs that could explode if you are not careful,” Councilman Landry said. “If there are alternative materials to use that are safer, I would obviously be in support of that, but ultimately, I don’t know what say the council has. As long as they are within EPA limits, government can’t tell business which chemicals to use. Those are business decisions they have to make on their own.” If government and the industry viewed serious accidents as more likely, it would take dangerous materials more seriously, said Orum, the chemical safety consultant who works with public-interest groups.

“These are low-probability, high-consequence events, which is why any individual company is not, by itself, motivated to make potentially expensive changes to a safer technology,” Orum said. He too likens the HF risk to the Deepwater Horizon catastrophe: “The BP oil spill [in the Gulf of Mexico] showed us that worst-case releases actually do happen.” In Torrance, ExxonMobil stopped using HF only after a series of chemical explosions in the late 1980s, including a 17-hour fire in the alkylation unit that killed one worker, injured 12 other people and caused $17 million in damages. While the acid itself was not a direct cause of any of the casualties, the collateral damage inspired local government officials to give refinery operations a closer look.

In 1989, the city of Torrance sued ExxonMobil, then known simply as Mobil, asking the courts to declare the refinery a public nuisance and let the city regulate it. Before the case went to trial, Torrance stopped its suit in exchange for Mobil’s agreement to a consent decree that required the company to modify or phase out hydrofluoric acid and pay for the appointment of a safety adviser to monitor compliance. Torrance area activists say other communities shouldn’t wait to lose lives before demanding companies operate more safely.

“It’s night and day after something happens,” said Yuki Kidokoro, southern California program director of Communities for a Better Environment. “It shouldn’t have to be that way.”

After 50 years living seven miles from both Chalmette Refining and Murphy Oil, Joy Lewis gave no more thought to smokestacks exhaling thick puffs of white-gray smoke than to leaves blowing in the wind. Then her daughter died of bone cancer at age 41. She and her husband, John Lewis, grocers by trade, began to pay attention to stack smoke and the sulfurous odors that wafted from the refineries. They spoke to their neighbors and realized their daughter was not the only victim of bone and blood cancers, types of malignancy often linked to air pollution. The couple, who had never before been environmental activists, started to get involved with the Bucket Brigade, testing the air around their home and eventually participating in a lawsuit that forced Chalmette Refining to pay state penalties for air pollution.

Lewis and her husband say they wish the refineries would take more responsibility for the risks borne by the community.

“It’s not that we want to close the refineries,” she said. “There’s no way little people like us could do it, but they make enough money that they could change things, make it a little safer for the community.”

An easy first step would be replacing dangerous HF with the modified version used in Torrance, they say.

“I just don’t trust their ability to be safe,” John Lewis said. “They used to have a system set up where you could call in to check safety conditions at the refinery. They had a big fire there a few years back, so while the refinery was in flames … I called in and ask what’s going on and the recorder says, ‘everything’s fine, operations normal.’ ”

The Center for Public Integrity and ABC News contributed to this report.

Correction 02/28/2011: A map originally published with this article showed ConocoPhillips Alliance refinery erroneously . The map has been updated.

This is a very important and compelling story. Something needs to be done to prevent further damage to Louisiana’s people and the environment.

very good article. intersting that all five refineries deferred comment to Washington, DC lobbyists. if they have decided not to be good neighbors, at least they could engage in dialogue.