As a chef in New Orleans, I rely on fish and seafood for my livelihood. The seafood from the Gulf of Mexico and its waterways is integral to my menu and to every restaurant that benefits from New Orleans’ reputation as a world-class food city.

What would New Orleans’ culinary tradition be without fresh catch for our seafood gumbo, oysters Rockefeller, crawfish etouffée, and shrimp po-boys?

Along with other chefs, fishers, and eaters, I have relied for years on bipartisan and science-based management of Gulf fish stocks to maintain this precious natural resource.

We all learned in the 1980s that without proper management, iconic dishes like blackened redfish could suddenly disappear from menus when the stocks had been completely depleted.

The plight of the redfish is a cautionary tale but thankfully led to a bipartisan consensus to reduce overfishing through legislation, in particular the Magnuson-Stevens Act, the federal law that governs U.S. fisheries.

To protect against extensive overfishing by foreign fleets, the 1976 law extended U.S. jurisdiction off our nation’s coast to 200 nautical miles. Through bipartisan cooperation, Magnuson-Stevens has successfully rebuilt more than 40 fish stocks.

In my conversations with chefs and fishers around the world, I have been struck by a shared acknowledgement that the United States has managed to get fisheries management right, an uncommon feat for an industrial nation. We are seen as a nation where fish conservation is a shared process, somewhat immune from the political fights surrounding other issues.

Treating our land and oceans in a way that preserves them for future generations should be a shared value. Our children and grandchildren will thank us.

But the Trump administration, abetted by House majority whip Steve Scalise, R-Metairie, has joined a disturbing trend. By politicizing the issue they are reversing a decades-long bipartisan effort, joined by coastal states and the federal government, to rebuild red snapper populations in the Gulf of Mexico. Abandoning a more thoughtful, science-based policy further threatens an already fragile ecosystem.

Memos between top officials show that the Commerce Department knowingly allowed overfishing of red snapper.

Under pressure from Scalise and a small group of Gulf Coast congressmen, Commerce in June announced that it would extend the federal recreational red snapper season from three to 42 days, a victory for certain recreational lobby groups, but a devastating blow to red snapper stocks and everyone who relies on them for their livelihoods.

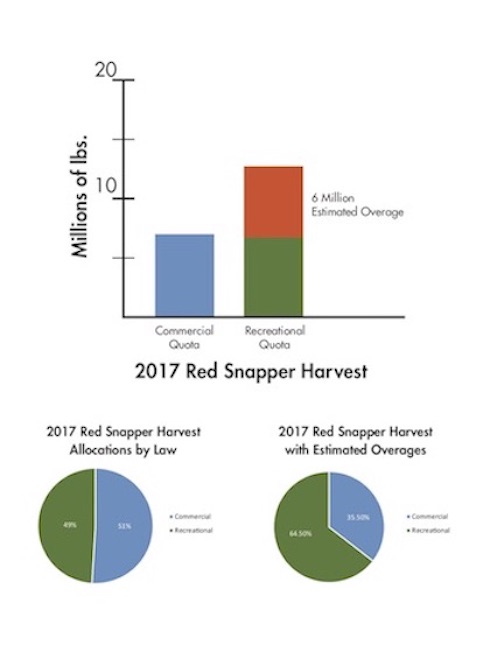

Documents revealed through a lawsuit by environmental groups show that Commerce knew it would lead to an overage of about 40 percent above a sensible limit.

This intentional violation of the law was a collaboration between certain recreational fishing interests and the Trump administration. The goal was to intentionally create a crisis in the fish management process so Congress would hand over more control to state governments and allow more recreational fishing by a relatively small group of wealthy sportsmen.

The issue has been cast as one of equity, allowing recreational fishers more access to Gulf snapper. But the vast majority of the public accesses its seafood via markets and restaurants. Recreational deep-water fishers, whose boats typically cost hundreds of thousands of dollars, already have secured almost half of the annual snapper limit, a figure vastly out of scale with their proportion of the population.

The decision to extend the snapper season is part of a greater effort to undermine science-based marine management under Magnuson-Stevens. Bills recently introduced to Congress — such as H.R. 3588 and H.R. 200 — are just two that would weaken federal protections and favor special interests.

But this issue is more important than red snapper. It’s about all species in our national waters, those that are managed and harvested recreationally and commercially, as well as those forage fish which are prey for those species.

Our fisheries and ocean ecosystems are distressed, from dead zones to ocean warming and acidification. The last thing they need is more pressure from overfishing.

Given the interconnectedness of our coastal/ocean ecosystems, a change to a less science-based approach to fisheries management will have wide and long-ranging consequences to both the snapper and the overall health of our coast. Fresh-water, salt-water, and land-based animal and plant species are impacted — as are the millions of people who inhabit the nation’s coasts and make their living plying its waters and enjoying its culinary bounty.

Being thoughtful and cautious about how we treat our environment should never be politicized. Treating our land and oceans in a way that preserves them for future generations should be a shared value. Our children and grandchildren will thank us.

Chef Dana Honn owns and operates Carmo, a tropical cafe and bar in downtown New Orleans. He partners with the Gulf Restoration Network on issues of conserving marine life.

Views expressed in the Opinion section are not necessarily those of The Lens or its staff. To propose an idea for a column, contact Lens founder Karen Gadbois.