NEW ORLEANS ― Invariably, someone brings up the anatomically-shaped balloons.

About a year ago, a bachelorette party from Texas rented a house through Airbnb on Ursulines Avenue in Treme, a residential neighborhood close to the bars and restaurants of the French Quarter.

The women tied inflatables shaped like penises to the front of the house, perhaps not realizing that the neighbors ― families and other longtime residents ― might mind.

“My oldest son woke up and there was an inflatable dildo taped to the house next door and I was like, ‘We’re out of here,’” said Christian Rhodes, a 36-year-old lawyer whose clients include the Greater New Orleans Hotel & Lodging Association and Uber.

He sold his house last year. “I’m not explaining to a 6-year-old what an inflatable dildo is.”

The balloon incident was when Janice Coatney realized her neighborhood had changed. She works at a nearby medical center and lives across the street from the house in question with her husband and teenage son.

“Before Airbnb, you had neighbors you could depend on. They looked out for you. If you went out of town, they’d get your mail, your paper,” Coatney said, standing on her front stoop on a typically stifling day in August, an anti-Airbnb signed taped to her window. “You just had more of a neighborly neighborhood.”

As if on cue, an Uber pulled up to a house across the street. A middle-aged passenger stepped from the vehicle and rolled his suitcase up to the front door, punched a code into a keypad and disappeared inside ― another temporary resident arriving at a short-term rental.

In Treme and several other neighborhoods across this historic city, residents say their neighbors are vanishing, pushed out by rapid, Airbnb-fueled gentrification. Desirable neighborhoods are turning into de facto tourist districts inhabited by visitors from around the world. A few renters have been kicked out to make way for travelers. Rents and home prices are up. The sound of suitcases rolling along the sidewalk has become as familiar in certain neighborhoods as brass bands, ambulance sirens and bounce music.

Courtesy of Airbnb and other short-term lodging services, as well as a new city law that makes it easy to transform your home into a vacation rental, thousands of residents and out-of-town investors are renting homes one day at a time to tourists instead of longer-term to locals. Others are simply selling their homes to developers that renovate and rent them out short-term. One company has even erected a residential building that makes the easy ability to Airbnb your apartment part of the sales pitch.

New Orleans, home to fewer than 400,000 people, has always been a tourist town, and locals have long complained that throngs of out-of-towners endanger the city’s authenticity. But Airbnb and other short-term rentals threaten that authenticity in a new way. Parts of the city were already gentrifying when Airbnb started to grow a few years ago, but the rise of short-term rentals appears to have accelerated that process.

This new kind of Airbnb-powered gentrification comes with all the downsides of traditional gentrification — home prices and rents are going up, lower-income residents and people of color are moving out — but with fewer upsides. Tourism and gentrification typically bring cleaner streets and less crime, but tourists don’t stick around to clean up the neighborhood, vote in local elections or lobby for better schools.

Over fierce objection from some affordable housing groups and neighborhood associations, the city now allows people to turn entire houses, apartments and half-duplexes into short-term rentals, removing them from the long-term rental market. In June, The Lens, a nonprofit investigative news site based in New Orleans, found that 70 percent of short-term rental permits allowed for so-called “whole-house rentals” at least 90 days per year.

“If you have the money and the means, it’s easy to buy houses in New Orleans, evict tenants and turn homes into tourist lodging,” said Breonne DeDecker, who works for a local affordable housing nonprofit group.

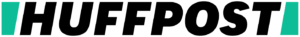

Locals in certain neighborhoods have been complaining about short-term rentals for the past few years. But until the new law passed, it was difficult to know exactly how many there were and where they were concentrated. Since April, the city has been tracking licenses issued to people who want to rent out their rooms, houses or apartments. The Lens and HuffPost partnered to analyze the data.

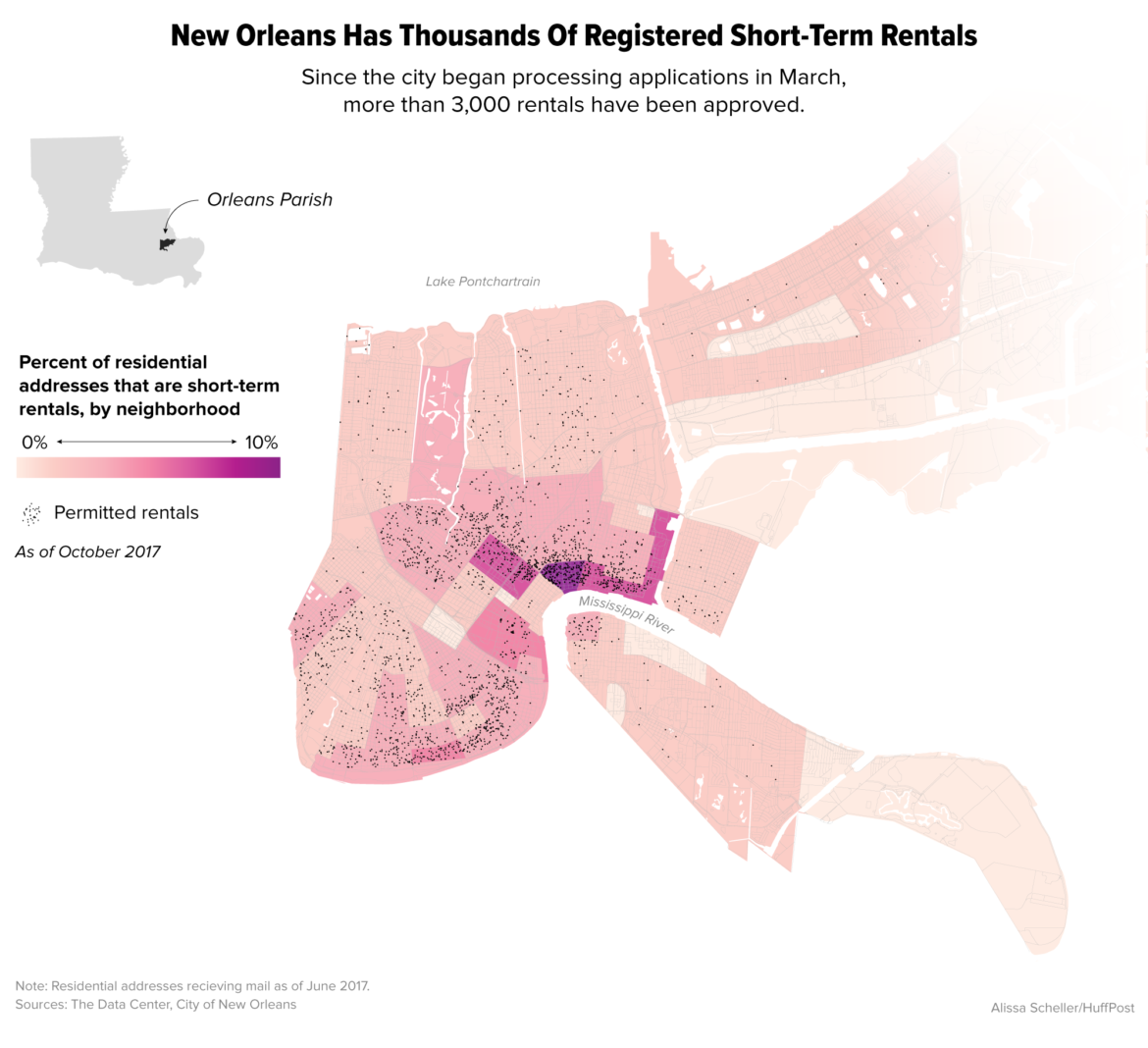

We found signs that short-term rentals are contributing to the transformation of a handful of the city’s most distinctive neighborhoods, particularly the ones closest to the French Quarter. In 15 neighborhoods, including Treme and Bywater, short-term rentals make up at least 3 percent of residential addresses. That’s a considerable slice of the city’s most desirable real estate.

In the Marigny, next to the Quarter, one in 10 residences are registered as Airbnbs. In the Central Business District, which is seeing a boom in luxury condos, 5.8 percent of residential addresses are licensed for short-term rentals.

More than half of the units in a new building called the Maritime are registered as short-term rentals. In another building, Saratoga Lofts, it’s 28 percent. DeDecker’s housing group has filed a complaint over both buildings, saying their government-backed mortgages don’t allow short-term rentals.

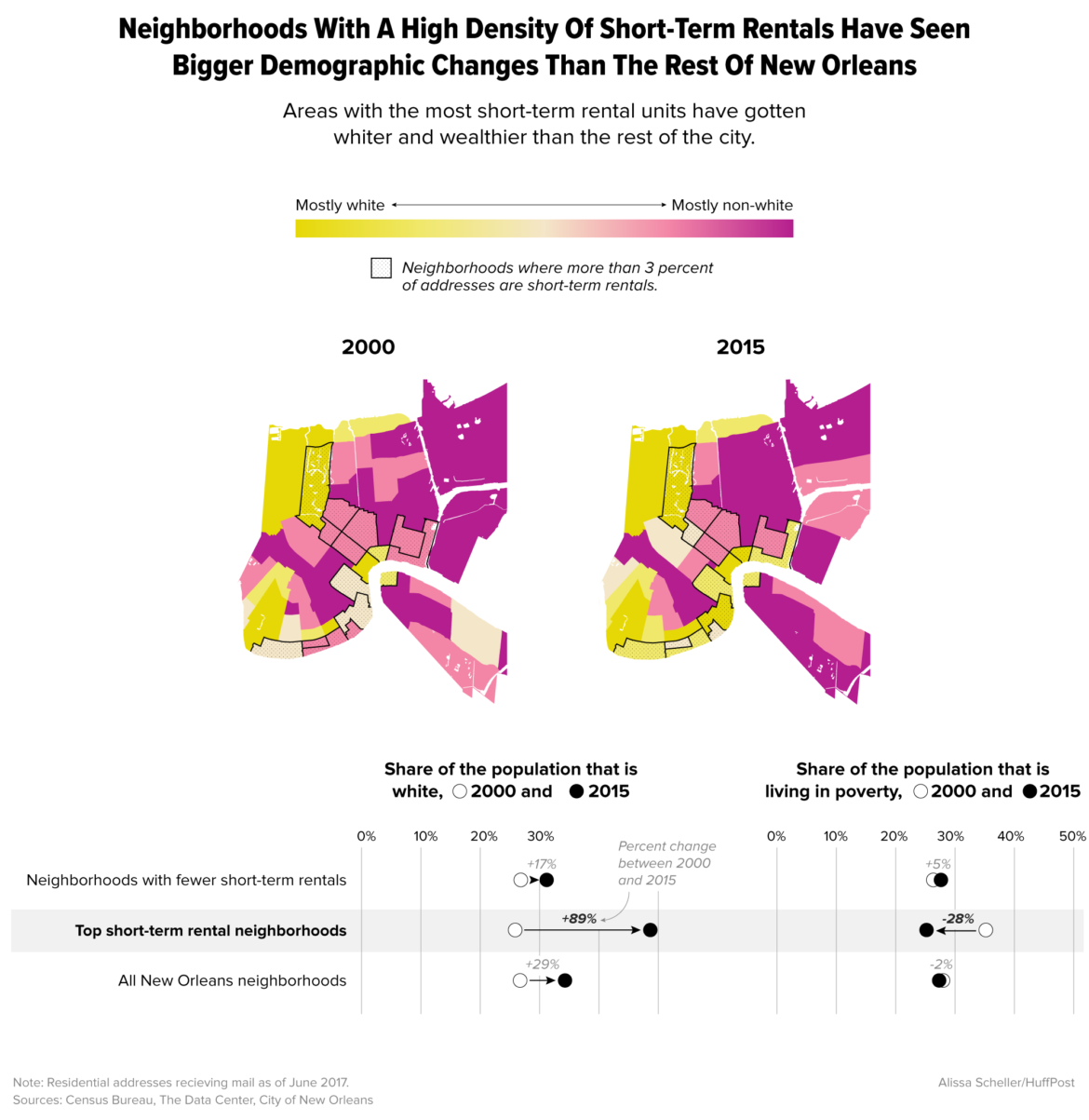

Many neighborhoods have become richer and whiter as the city has been rebuilt after Hurricane Katrina. The change has been particularly dramatic in the “sliver by the river,” which saw less flooding after the storm, Tulane University geographer Richard Campanella has noted.

Those same neighborhoods are now ground zero for Airbnb. The neighborhoods with the highest concentration of Airbnbs are nearly 50 percent white, compared with 34 percent in the city as a whole.

Coatney’s street in Treme embodies this new reality: Ten of the 16 homes on her block are licensed as short-term rentals. In Treme, 6 percent of residential addresses have a short-term rental license.

“Every new construction in this neighborhood has become a short-term rental,” said Meg Lousteau, one of Coatney’s neighbors.

Lousteau, 48, a historic preservation advocate, has lived in Treme for 14 years and has been fighting the influx of Airbnbs. “I love living in a historic neighborhood,” she said. “There’s just chance encounters and interactions with people you would never get living in a cul-de-sac in a suburb.”

Lately, though, more and more of Lousteau’s encounters are with out-of-town 20-somethings looking to party, she said.

How New Orleans Got Airbnb’d

Hurricane Katrina turned New Orleans into even more of a global destination than it already was, adding attention to the city’s distinctive music, culture and food.

Last year, a record 10.5 million tourists descended upon the Crescent City and spent $7.4 billion, according to the New Orleans Convention and Visitors Bureau.

Together, the places they stay, the cars they rent and the businesses they patronize make up the largest industry in the city. For better or worse, New Orleans needs tourism to survive.

The city’s popularity, in addition to a significant loss of housing stock in the wake of Katrina, has contributed to an increase in rents and home prices, particularly in areas that didn’t flood. Since Katrina, home prices have risen 46 percent, according to real estate data from 2015. Wages, however, have not kept pace, leading many renters and homeowners to seek ways to boost their income.

“The more Airbnbs in a city, the higher rents get for local residents,” said David Wachsmuth, an assistant professor in the School of Urban Planning at McGill University, who is studying how Airbnb affects housing and gentrification.

Some studies have found that even a small number of Airbnbs, particularly those operating for big chunks of the year, can make neighborhoods more expensive.

One doesn’t have to be an economist to understand what’s happening. Apartments that used to house long-term tenants are furnished and listed on Airbnb and VRBO (Vacation Rentals By Owner). Local homebuyers compete with out-of-town investors looking to cash in. “You’re shrinking supply, but not demand,” Wachsmuth said.

A 10 percent increase in Airbnbs causes a 0.4 percent increase in rents, according to a study of 100 U.S. cities published in July.

10%Increase in the number of Airbnbs causes a…0.4%Increase in rents, according to a recent research paper

It sounds like a small matter― and Airbnb insists it’s insignificant ― but it translates into large increases, Wachsmuth said. The spread of Airbnbs isn’t uniform throughout the city: Some neighborhoods are wildly popular and the rent increase in those areas could be as much as 50 percent, he said. “You’re talking 1 or 2 percent [rent] increases solely attributable to Airbnb,” he said.

Airbnb disputes the idea that it is responsible for taking homes off the market that locals could use, spokeswoman Laura Rillos told HuffPost in a statement. Rillos pointed to a 2016 Loyola University study that found Airbnb did not have a discernible impact on rental prices in New Orleans. But the data was grouped by ZIP code rather than by neighborhood, and the real estate market in the city varies widely within the same ZIP code.

“Most New Orleans Airbnb hosts share the homes in which they live and do so, in large part, to afford to stay in their homes,” Rillos said, adding that most rent out their homes just a few times a year. She pointed to a 2015 survey of local Airbnb hosts by the company in which 65 percent said they were renting out their homes to make ends meet; a few hundred said the service had saved them from foreclosure. “We are committed to working with the City of New Orleans to protect long-term housing stock,” Rillos said.

Rillos didn’t comment on The Lens-HuffPost analysis and reporting.

How many Airbnbs are there in your neighborhood?Use our Airbnb tracker to find out.

Housing advocate DeDecker has a different take. Airbnb is fueling a second wave of gentrification in the city, she said. As short-term rentals price the original hipster and artist gentrifiers out of the most popular neighborhoods, they’re moving into other neighborhoods that are home to lower-income residents, typically people of color, and displacing them.

“The tourists are replacing people who have more economic power,” DeDecker said, noting that this has happened to many of her upwardly mobile friends. “They can pay more money in rent than the family they’re going to be replacing.”

DeDecker has watched as her own neighborhood in Treme has been overrun by tourists, who she said gawk at her tattoos when she’s out walking her pit bull. “It’s like I’m part of a tableau that they’re digesting.” Replacing locals with tourists “is like creating a zoo with people in it.”

“So much of the ‘cool’ culture of New Orleans is tied to neighborhood identity,” DeDecker said. She brought up the example of Mardi Gras Indians, a local tradition in several black neighborhoods in which groups of men dressed in colorful, Native American-inspired costumes parade through the streets. She asked, what will happen to this tradition when the Indians no longer live in their neighborhoods?

It’s hard to know how many people have been evicted to make way for Airbnb. The Lens and HuffPost spoke to two renters who said they were forced to move and had to pay more when they found another place.

Eric Aufderhar and his wife, a medical student, got 30 days to move out of their rental in the Fairgrounds neighborhood so the landlord could start renting it to tourists. The couple found a place quickly, but it cost $1,250 a month ― $250 more than they had been paying. They were able to afford the first month’s rent and a security deposit because they had been saving up to get married.

“We were lucky that we had that savings. It could easily have ruined a family,” Aufderhar said. “Home should be this safe place.” He and his wife had their new landlord guarantee in the lease that he wouldn’t kick them out to Airbnb their apartment.

New Orleans isn’t the only city to struggle with the rise of Airbnbs. Global tourist destinations like San Francisco, New York, Berlin, and Amsterdam have passed restrictions on the use of the service to protect neighborhoods from becoming hollowed out. Some regulations are far stricter than those in New Orleans, and in some cases they have sparked legal battles. The laws typically limit how often you can rent out your home. In Europe, some cities fine Airbnb when homes are listed illegally. Enforcement varies.

Unlike these places, New Orleans has made it easy for people to Airbnb their apartments and houses. You don’t even have to be a homeowner or a resident. In December, the city legalized short-term rentals everywhere, except most of the French Quarter. (The city has long restricted short-term rentals in the Quarter, and it put a moratorium on new hotel rooms there in 1969 in an attempt to preserve the neighborhood’s character.)

Previously, leasing an apartment in New Orleans for less than 30 days was illegal in most neighborhoods. Still, enforcement was nonexistent and Airbnbs were thriving.

Proponents of the new law say it enables residents to benefit from the booming tourist industry while allowing for oversight and giving some tax revenue to the city.

“New Orleans was lucky with some progressive leadership. We were able to get ahead of the curve and embrace” Airbnb, said Eric Bay, who runs the Alliance for Neighborhood Prosperity, which lobbied for the law and represents homeowners who have 1,300 short-term rental listings.

Bay said New Orleans’ lack of affordable housing has more to do with stagnant wages and blighted properties than the growth of Airbnb.

He lists his Uptown home on Airbnb for $2,000 a week. He also manages about a dozen short-term rental properties for others, including a couple on Bourbon Street.

Under a basic license, people can rent out houses or apartments for up to 90 nights per year — nearly every weekend night.

Another type of license allows homeowners to offer part of their houses year-round if they prove they live there. This provision applies to half of a duplex, a common type of rental housing in New Orleans, if the owner lives in one of the units. Airbnb opponents consider this a major loophole, saying it encourages owner-landlords to convert their second unit to a short-term rental.

Homes in mixed-use areas — even a single commercial block in an otherwise residential neighborhood — can be rented on Airbnb every night of the year, though just last week a city council member said that part of the law needs to be tightened. The mix of residential and commercial properties is part of the fabric of New Orleans’ oldest neighborhoods, where a corner bar could be located a couple doors from a stately home.

All one needs to get started is a permit, which costs anywhere from $50 to $500. There are some restrictions on how many people can stay in an Airbnb — you can’t rent to more than 10 people at a time, for example. Violators can be fined up to $500 a day. Some people say that’s too low, noting that an Airbnb operator can make that back in a weekend. As of late October, the city has fined 117 properties for violations, according to the mayor’s office.

Airbnb collaborated with the city on the new law and helped make the registration process simple, company spokeswoman Rillos said. Since the licensing system began in the spring, she said Airbnb has removed thousands of hosts who failed to apply for permits.

So far, the city has issued 1,236 violation notices and levied $217,000 in fines. It has collected $650,000 in license fees, about enough to buy a nice, renovated house in Faubourg Marigny. In addition, the city is collecting a nightly booking fee to support affordable housing — although that money has not been used yet.

City officials acknowledged that short-term rentals play a role in pushing rents up. “We’re cognizant and working on it,” said Ryan Berni, deputy mayor for external affairs. But he emphasized that Airbnb is only one of many factors contributing to New Orleans’ housing crunch. “The dynamics in the housing market are much larger than this one issue,” he said.

The Post-Katrina New Orleans: Richer, Whiter

As with most issues here, it’s impossible to ignore the racial dynamics of housing. Since Katrina, this majority-black city has gotten a lot whiter. About 118,000 African-Americans have left the city since the storm, compared with a drop of 24,000 white people, according to Census data. Since 2000, the percentage of residents who are African-American has ticked down from 67 percent to 60 percent.

Some black residents simply didn’t want to return after evacuating. Others had no homes to return to. The city’s public housing agency demolished all the major housing developments, which were mostly occupied by African-Americans. In their place are developments with a combination of public housing, vouchers and market-rate units — but there aren’t as many public housing units as before.

The city’s thriving black middle class struggled to recover. Because of the way the state doled out recovery grants — they were based on the value of the home, not the cost to rebuild it — housing advocates said black homeowners ended up getting less money than whites.

While the city doesn’t track racial data of Airbnb permit holders, our analysis of permit data shows that neighborhoods with the highest concentration of Airbnbs have gotten whiter than the rest of New Orleans.

Research from other cities shows that whites are more likely than black people to offer their homes on Airbnb. Those with distinctly African-American names are 16 percent less likely to be accepted by hosts. Responding to these reports, Airbnb has made efforts to make its service more diverse.

Coatney, who is black and lives on the block where the bachelorette party hung the penis balloons, said white people make up the majority of Airbnbers she sees in Treme, a historic black neighborhood popularized by the HBO series.

There’s no question Airbnb has enabled some locals to bring in more money.

Alton Osborn, a 55-year-old black artist and New Orleans native, said Airbnbing the back room of his house in the hip Bywater neighborhood has changed his life. “It’s just freed me up, because all these years I was struggling as an artist,” he said, sitting in the snug bedroom where tourists crash after staying up late on Frenchmen Street.

After Katrina, Osborn made a living by designing and selling clothes. He paid about $100,000 for the spacious, shotgun-style house, in what then was a somewhat run-down neighborhood.

The previous owner was convinced New Orleans was declining. Instead, the neighborhood got fancy. “The Bywater became the new Brooklyn,” Osborn said. “It was like everyone was moving here.”

A year ago, he and his fiancée hit on the idea of an Airbnb. Now, they rent out this back bedroom with jazz posters lining the walls and an airy bathroom. Renters get access to the backyard with a hot tub and outdoor shower. During the slow season, they charge $125 to $150 a night. During Mardi Gras and Jazz Fest, it goes up to $200 or $250, he said.

Osborn retired from clothing design. His fiancée quit her job and opened a bakery nearby, where Osborn said 40 percent of the customers are tourists staying at Airbnbs.

Peter Horjus, a statistician who has lived in Marigny for 17 years, hasn’t been as lucky. He recently learned that the appraised value of his 2,000-square-foot, double-shotgun home shot up from $246,500 to $426,900. His annual property tax bill nearly doubled to $5,250.

In a column for The Lens, Horjus wrote that property values have soared as investors buy homes, renovate them and list them on Airbnb.

“Everyone I know lives next door to an Airbnb,” Horjus said in an interview. “And you start hearing about friends getting kicked out of apartments, or their landlords telling them they’re raising their rents drastically because otherwise they’re gonna make an Airbnb to make more money.”

Horjus went to City Hall to argue for a lower tax bill and got a bit of a break. So far, he hasn’t raised the rent for his tenant, who pays just $950 a month — a steal, considering he could put the apartment on Airbnb or VRBO for $100 a night or more.

But he worries that he’ll someday be forced to join the ranks of Airbnb hosts in his neighborhood. “At a certain point,” he said, “I will just be like, ‘Fuck everyone,’ and rent it out if I just feel like I completely lost, my neighborhood is gone, people I know are gone — this neighborhood is owned by rich people who buy these houses to rent them to tourists.”

Meanwhile, Back On Ursulines Avenue

The man who walked into the short-term rental across the street from Coatney’s house on that hot August day was 49-year-old Kyle Paulson, a white engineer from Chicago in town for a conference.

He was set to stay in the beautifully renovated, four-bedroom home with four colleagues for four nights. They paid $2,500, a better deal than they could get in a hotel, Paulson said. The listing on Homeaway.com touts its location in “historic, world-famous Treme” and puts the nightly fee at $1,000.

Paulson said the house, with its fresh wood floors and brand-new appliances, was great. But Treme? “It looks like a shitty neighborhood,” he said. “I don’t know. I don’t live in New Orleans; I have no idea.”

Homeaway.com did not respond to request for comment.

Christian Rhodes, the father on Ursulines Avenue who decided to move after the penis balloons, said he knew he was contributing to the gentrification of Treme when he bought his home in 2012 for $168,500. Through his job, he saw the growth in the tourism industry and felt it was the right time to buy.

The neighborhood was a bit down on its heels when Rhodes moved in. Residents said things could get a little dicey at night. The area near Ursulines Street is perhaps best known for an incident at a bar called Joe’s Cozy Corner.

In 2004, the beloved owner of the bar, Joseph Glasper, shot and killed a man outside after a jazz funeral for a local musician named Tuba Fats. The bar, a hangout for jazz musicians and a stopping point for many second-line parades, soon closed. Its old sign now sits in front of Alton Osborn’s Airbnb.

Today, Joe’s bar is a coffee shop where hipsters and tourists stare at laptops and listen to jazz via an iPhone and some speakers.

“I think that gentrification can occur authentically,” said Rhodes, who is black. “I was doing that.”

His mother-in-law grew up in Treme, and her family there goes back nine generations. The Rhodeses were the fourth generation of black professionals to live in that house since it was built in 1841, he said. When they bought it, he said, it was in pretty rough shape. It took a year to renovate.

A few years later, Rhodes wound up buying the house next door. He said he had grown tired of watching prostitutes use the blighted building to work. He paid about $100,000, intending to fix it up and sell it.

But by 2016, Rhodes saw Airbnbs taking over the block.

That year, he found buyers for the house next door. The men, who appeared to be a couple, seemed to want to live in the house full-time. They said they were moving to the city from Boston and Chicago, but they didn’t reveal much more about their intentions, Rhodes said.

Days after the deal closed, he said, the plan became clear. The buyers quickly furnished the house and listed it as a short-term rental. The following weekend, 12 women from Texas showed up. The inflatable penises soon followed.

That was the end for Rhodes.

Even though he represents the hotel industry, which opposed the new short-term rental law, he said he’s not necessarily opposed to Airbnb itself. Rhodes also represents Uber and is a fan of the so-called sharing economy, he said.

He just didn’t want to live in an area dominated by short-term rentals. “On our block we didn’t have neighbors; we had guests living on our block Thursday to Sunday,” he said. “Airbnb kind of guaranteed there would be no families.”

Rhodes and his wife put their house on the market and quickly found buyers, a man and woman who said they planned to live there. They, too, turned the house into a short-term rental.

The Rhodes family sold both houses for a total of $1.35 million.

Now, he and his family live in Gentilly, a lower-density area farther from the river. “We pocketed a lot of money,” he said. But he said he feels guilty that both homes became vacation rentals.

Lousteau said she was “heartbroken” when Rhodes sold his home to Airbnbers. She’s lived in New Orleans since she was a teenager, and in Treme since a few years before the storm. She painstakingly renovated her 2,800-square-foot, 1840s-era home with its wide-plank wood floors and a yard packed with Meyer lemon and blood orange trees.

As executive director of an association of French Quarter property owners and residents, she’s a passionate opponent of the city’s Airbnb regulations. In her neighborhood, she’s the resident vigilante when it comes to policing the behavior of short-term renters.

It was Lousteau who came along with Janice Coatney to tell those Texas women to take down the penis balloons. An “unfortunate incident,” she said. Lousteau and Coatney told the women that people actually lived there. “They were like, ‘Fine, fine,’” Lousteau said.

Lousteau has approached young guys still drunk from the night before and asked them to put their shirts on, only to be cursed at.

“There’s no way to establish a relationship with these people so it doesn’t happen again next week,” she said. “They’re not going to be here next week.”