David Waggonner is the envy of most public-policy advocates: He can say his vision was endorsed by – ahem – God.

The architect’s vision was to convert 25 acres of prime New Orleans real estate worth tens of millions of dollars into a water garden as part of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan.

To be fair, Waggoner makes no claim about the Almighty’s endorsement.

But the nuns who own the property do.

“After Hurricane Katrina, we were keeping a vigil waiting for a vision on how we could best use the property to fulfill our mission and benefit the people of New Orleans,” recalled Sister Pat Bergen of the Congregation of St. Joseph.

“Then an architect came to us with his plan for the Mirabeau Water Garden, and we knew right away it was the vision we had been praying for.”

They not only signed on to Waggoner’s idea, they snubbed advances from developers and leased the property off Filmore Avenue and Bayou St. John to the city for a dollar a year for 99 years.

It’s no stretch to say the nuns’ multi-million dollar gift was heaven-sent for advocates of the water plan. They are trying to reverse a mindset that has been a New Orleans tradition for 300 years: Every drop of rain is an enemy that must be pumped out as soon as it lands.

Instead, the plan says if the city keeps some of that rain inside the levees, it can actually reduce flooding from rainfall, slow the subsidence problems plaguing streets and buildings and have a more beautiful landscape.

Rain gardens are a key tool in accomplishing those goals.

Most of the city’s flooding has happened when torrential downpours overwhelm the drainage canals and pumps, backing up water into streets and cars – and in many cases, homes.

By storing water on the surface, rain gardens can slow the movement of stormwater into the system.

Just as importantly, surface storage also allows more time for rainwater to seep into the soil and restore the water table, which can help reduce the subsidence.

Post-Katrina New Orleans had plenty of empty lots for small rain gardens, but helping relieve flooding in whole neighborhoods requires a grander scale.

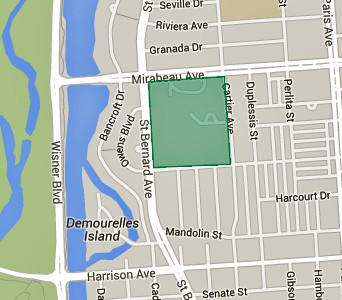

Waggonner was scanning aerial photos of the city looking for larger properties when his eye was drawn to a large green, empty section in the Filmore area of Gentilly.

“We were like hawks looking for anything that was open – and a 25-acre tract really caught our attention,” he recalled.

He would learn that the property featured a building that had been used by the Congregation of St. Joseph since 1952 for a novitiate, senior center and Montessori pre-school. After Katrina, the congregation spent $250,000 having the building pumped dry only to see it ruined by a lightning-caused fire. In 2007, they had it demolished and began their vigil on how best the property could be used to fulfill their evolving mission.

“Our mission as a community now is to live our lives in oneness with nature,” Bergen explained. “Our commitment is to strengthening, healing and renewing nature, and by doing that healing people and bringing them closer to God.”

Developers were sharing a different vision with the congregation. In a neighborhood where home values run about $123 a square foot, the ultimate resale price of the property “would easily be tens of millions of dollars,” said Jeff Hebert, director of the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority.

But the developers didn’t stand a chance once Waggoner showed up.

“The drawings the architect showed us fit that vision so perfectly,” Bergen said.

The proposal includes not only a series of ponds for holding water, but educational exhibits to help teach residents why working with water is helpful, recreational fields and green spaces.

“It would not only help serve the entire city be reducing flooding, but it will also be a space for recreation and education that can benefit everyone,” Bergen said. “This project will help heal the earth, and heal the community.”

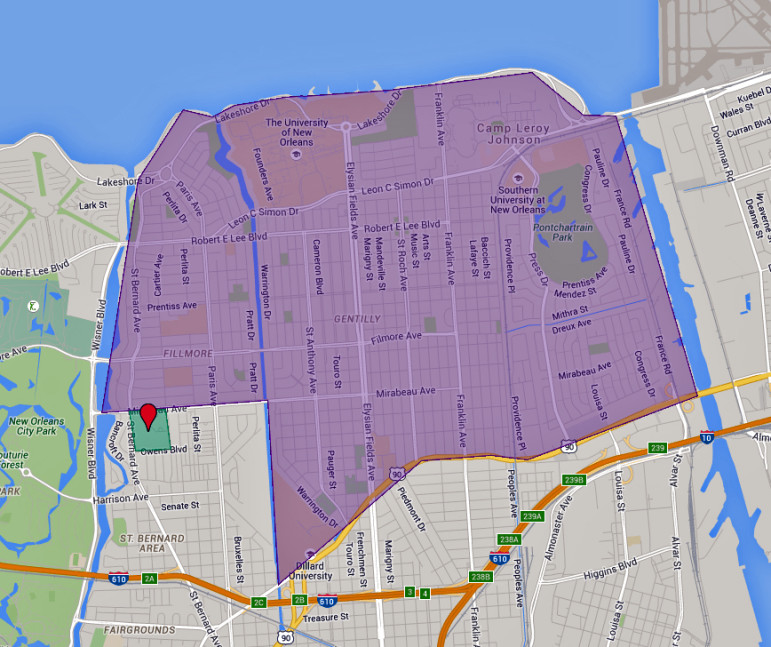

The healing starts by reducing flood anxiety for neighborhoods that rely on Pump Station No. 4. That includes almost everything between Bayou St. John, the Industrial Canal, U.S. 90 and Lake Pontchartrain.

Preliminary modeling indicates the 25-acre tract could remove up to 9.5 million gallons of stormwater from the drainage system in the surrounding 3,785 acres during heavy downpours.

The water garden is designed to relieve Pump Station No. 4.

That would eliminate the threat of flooding in a 10-year rain event, reduce flooding by 72 percent during a 100-year event, according to hydraulic engineers working on the project.

Those figures were critical in acquiring a $12 million grant from FEMA for the initial engineering and design of the garden. And those plans helped the city secure the $141 million grant from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development’s National Disaster Resilience Competition, which will provide the remainder of the estimated $30 million cost for the project.

Waggoner is equally excited about the role the water park will play in the tamer daily showers that are part of New Orleans life.

“During the showers, we’ll have water moving across the surface serving as a living demonstration of how important living with water is to the city,” he said. “Everyone concentrates on the deluges, but those are really pretty rare.

“It’s the daily role of these water gardens in educating the public that is also so important. We’re undertaking a sea change in the city’s approach to water. And the public has to understand how water work for us.”

Hebert, who heads the city’s resiliency effort, said the project’s multiple roles was a winner with federal officials doling out money.

“The project has four goals,” he said. “Flood reduction in the surrounding neighborhoods, helping reduce subsidence by putting more water back into the soil; education and outreach and — in dry times — recreation.

“And we’re working with mosquito and termite control so we won’t be breeding mosquitoes in the water garden.”

Plans call for the first phase to be completed by 2017. However the nuns are not putting the fate of their multi-million gift on good intentions but in a demanding lease. It lays out deadlines for stages of completion starting in 2017 and gives the congregation the ability to end the agreement if the city doesn’t meet their expectations.

“The land has special meaning to the congregation,” Hebert acknowledged. “So it’s very important to them that we do what we say we are going to do.”