One afternoon a couple of weeks ago, Michele Benson Huck was driving down Broad Place near St. Rita Catholic School. The school-zone flasher was malfunctioning — again — but she slowed down anyway.

The driver behind her responded by honking and trying to pass. Drivers routinely speed through during school hours, Huck said. “I just think it’s a matter of time before someone is critically injured or killed because people are in just such a rush,” she said.

Like the one on Broad Place, many of the school-zone flashers in the city don’t work properly.

They’re supposed to flash on school days from 7 a.m. to 9 a.m. and 2:45 p.m to 4:45 p.m. City code requires drivers to slow to 20 mph during those times, even if the flashers aren’t working.

Are there malfunctioning school flashers in your neighborhood? Take a picture and post it to Twitter or Facebook with the hashtag #schoolzones. Include the location and the time you saw it. We’ll keep track.

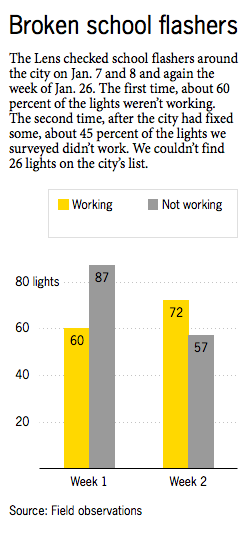

The Lens surveyed all the flashers on the city’s official list on Jan. 7 and 8. Six out of 10 — 87 out of 147 in active school zones — were malfunctioning.

The city, which is responsible for maintaining the lights, blamed the solar panels atop the light poles when we shared our findings in mid-January. But according to the manufacturer, the problem may be more elementary: dead batteries and improper installation.

Some of the broken flashers we observed in early January were on the city’s busiest streets. On weekday mornings this school year, cars have regularly zipped by Eleanor McMain Secondary School and Ursuline Academy on South Claiborne Avenue as the lights failed to activate.

The flashers in both directions weren’t working when The Lens surveyed them on Jan. 7. Later in the month, they were.

But on Saturday, the westbound flashers were on at 12:30 p.m. and again at 10 p.m. Drivers disregarded them.

Steve Myers / The Lens

This flasher on South Claiborne Avenue wasn’t working when we first checked, but it was the second time. However, over the weekend it was flashing when school wasn’t in session — including 10 p.m. Saturday.

A couple of weeks after we notified the city of our findings, we checked the flashers again. This time, more of them were working. About 45 percent of the lights we checked were broken (57 out of 129), down from 60 percent.

Landrieu spokesman Brad Howard said the city had fixed 20 to 30 flashers in the last month by replacing bulbs, reprogramming the lights and fixing circuitry.

“The City routinely assesses school zone beacon flashers and makes repairs,” he said by email. “We also typically see an uptick of malfunction reports from residents – and subsequent repairs by the City – when school resumes after an extended holiday break.”

He didn’t respond to a follow-up question asking if the city had received more complaints in January.

City Councilwoman Nadine Ramsey heads the Public Works, Sanitation and Environment committee. Kara Johnson, her chief of staff, said Ramsey’s office hasn’t received any complaints about malfunctioning flashers, but the city’s public works department told her they’re aware of the problem.

A problem throughout the city

Even with the repairs made in the last few weeks, there’s still more work to do. Of 10 flashers on the West Bank, only the two located in Algiers Point were working when we first checked. Last week, those same two were working. Four weren’t. Three displayed a low battery signal, blinking briefly in unison. On the last sign, one of the two lights was out.

Sometimes beacons flash when school isn’t in session — such as Jan. 19, when students were off for Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

And some flash at the wrong time of day. At 1 p.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 20, the beacons on the 2100 block of Louisiana Avenue were on. That was almost two hours before they were supposed to warn drivers to slow down as they approached Holy Ghost Catholic School.

Where the lights are connected to speed-limit cameras, this hurts the city’s pocketbook. Drivers who exceed 20 mph during the posted times aren’t ticketed if the flashers aren’t working, according to the city.

Eighteen flashers connected to speed-limit cameras weren’t working when we first checked, including both on Bienville Street near Pierre A. Capdau Charter School in Mid-City. The second time, 11 of them weren’t working.

Told of The Lens’ findings in mid-January, the city of New Orleans provided a statement from Lt. Col. Mark Jernigan, the city’s public works director.

“The beacons are solar powered and they may not operate during persistent overcast conditions,” he said in the statement. “Motorists are encouraged to be mindful of all posted roadway speed limits and pay especially close attention in school zones.”

The city’s bid specifications, however, say that the flashers are supposed to operate for a month without being recharged.

Jernigan said that city law doesn’t require beacons in school zones, but “they were added as an extra safety precaution.”

Such flashers have been found to reduce drivers’ speed more than signs alone. Cars slowed down 5 to 7 mph on roads with speed limits of 30 to 40 mph when flashers were present, according to a study by the Washington Traffic Safety Commission.

“If the light isn’t working, people will be less apt to respond appropriately,” said Dick Doane, who worked on the study.

What’s the culprit, solar panels or batteries?

The city has known about this for some time. During a June 2013 City Council committee meeting, two top city officials said the city’s revenue from speed-limit cameras was down in part because school-zone flashers weren’t working properly.

“If the lights aren’t on, we don’t issue the ticket,” said Chief Financial Officer Norman Foster. He added that “the equipment is just challenging to maintain.”

“I just think it’s a matter of time before someone is critically injured or killed because people are in just such a rush.” —Michele Benson Huck

Councilwoman Jackie Clarkson responded: “Well, that’s a shame. Is that in the process of being corrected?”

Chief Administrative Officer Andy Kopplin said Public Works was in the process of hard-wiring many flashers. He said Jernigan had a plan to fix the lights by Aug. 1, 2013, when school would be back in session.

Howard told The Lens that the city has hard-wired flashers “in at least five locations.”

There could be an easier solution: Replace the batteries and make sure the solar panels are installed correctly.

The solar panels are made by Carmanah, a Canadian company that specializes in solar-powered traffic systems. The company’s user manual recommends that its solar panels face the equator to catch the most sunlight. The Lens observed several beacons with solar panels that don’t face south, and even some pointed north.

“Full solar exposure is critical,” the manual reads. “Shading even a small portion of the solar panel will significantly reduce its ability to charge the battery bank.”

Some flashers in New Orleans are shaded by trees and installed under overpasses.

Another problem appears to be old batteries. Many of the malfunctioning flashers around the city blink quickly in unison, barely visible to drivers —the manufacturer’s signal for a low battery.

The lights were installed in 2008, and the batteries are supposed to last five to seven years.

Jack B. Harper Electrical installed them at a cost of $1.3 million, which FEMA covered as part of the Hurricane Katrina recovery. The company maintained the lights through 2011.

Now the city is responsible for maintenance. This year and last, the city has budgeted for three technicians to attend to the school lights and traffic signals. Depending on what needs to be fixed, the city or Harper handles it, Howard said.

Schools move; flashers don’t

A host of circumstances, ranging from shuttered schools to varying school calendars, contribute to the confusion regarding which zones are enforceable.

Many of the city’s schools never reopened after Hurricane Katrina, but the old school-zone signs are still there. In the years since, schools have opened in temporary locations and then moved to permanent homes. Many of those flashers remain, but they don’t work.

Last year, Harriet Tubman Charter School moved eight blocks down General Meyer Avenue, a major thoroughfare on the West Bank. The city says there are two flashers at the old location; there’s actually just one. The first time we checked, it wasn’t working. The second, it displayed the low battery warning.

And at the new location, the former site of O. Perry Walker High School, there are no flashers.

“People really speed down General Meyer,” said Tubman principal Julie Lause, “and we’ve definitely had some close calls.”

Over the summer, a charter network employee asked Ramsey’s office if the city would install flashers at the new school. One of Ramsey’s staffers relayed the request to Public Works.

“We have no intention of installing any additional school flashers at this time,” responded Cheryn Robles in an email, noting that there is a traffic light with a pedestrian crossing at an intersection in front of the school.

Adding to drivers’ confusion is the fact that the 40-some charter school networks have their own calendars, in addition to the private schools throughout the city. Some charters operate on a quarter system, with one or two weeks between quarters. Others are in session practically year-round with only a few weeks off in the summer.

Carmanah’s flashers can handle this, according to the user manual. They can be programmed for 500 days at a time, which the city required in its bid specifications.

The city doesn’t even know where all the flashers are. In response to a public records request, the city provided a list of all flasher locations, 163 in all. The Lens couldn’t find lights at 26 of them. In other cases, flashers were there but the school had closed or moved. Some signs were removed during construction.

Lause, the principal at Harriet Tubman, said school-zone signs remain posted in her neighborhood although the school is no longer there. She said that encourages people to ignore the signs.

“People are a little jaded,” she said, “like, ‘I don’t have to slow down because there isn’t a school there.’”

The following Lens staffers contributed to this story: Steve Beatty, Karen Gadbois, Abe Handler, Charles Maldonado, Bob Marshall, Steve Myers and Tom Thoren.