“Got that sinking feeling?”

A set of slides from a recent presentation by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration makes clear that the familiar figure of speech isn’t just a state of mind for residents of coastal Louisiana.

It’s a reality – and one that poses serious challenges to the region’s future.

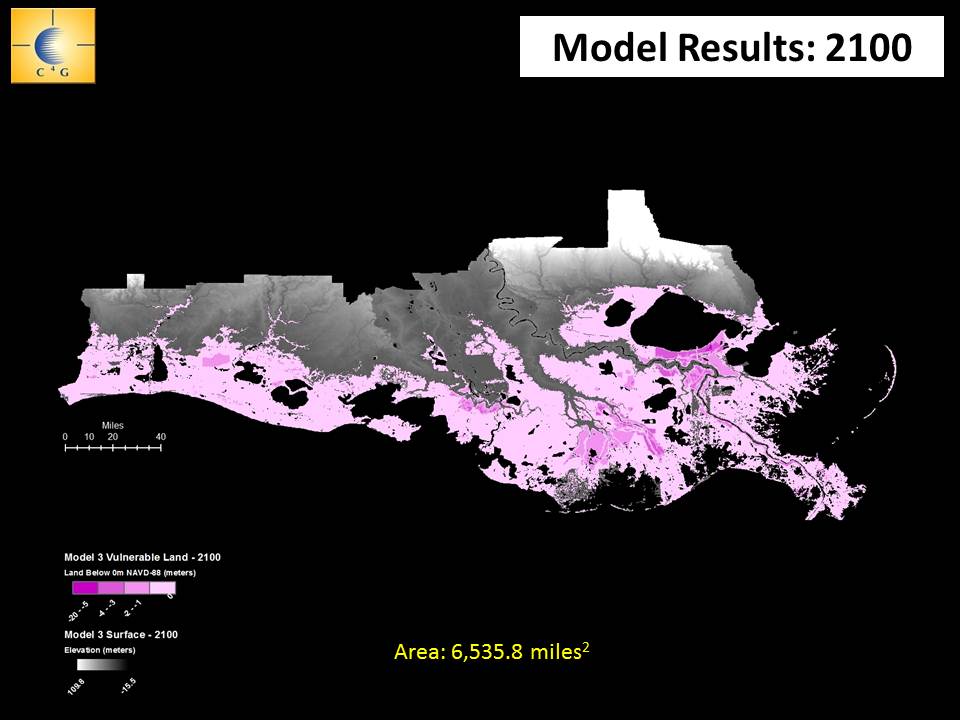

Produced by LSU researchers, the slides project Louisiana’s growing vulnerability to storm surge through the end of the century, as we get hit with a double-whammy: rising Gulf waters and the continued subsidence of a mud-starved coastal plain.

The projections show that by 2050, the combined forces could raise Gulf surges as much as four meters (13.1 feet) above current land elevations in the metro area. By the end of the century the entire coastal zone — all the way to the northern shorelines of Lakes Pontchartrain and Maurepas — would be vulnerable.

Granted, forecasting subsidence rates is very difficult, given the dynamic nature of land movement on the dying deltas that buffer most of the region from surge.

Compaction in some areas is expected eventually to slow subsidence, but no one is certain whether that mitigating dynamic will kick in before the end of the century, said Joshua Kent, of LSU’s Center for Geoinfomatics, whose team was tasked with developing a worst-case scenario.

Kent said the team’s model is based on subsidence rates recorded through 1997.

“The purpose of the exercise was to project how much of each parish would be susceptible to flooding from storm surge as we continue to subside while sea level rises; so we could only use the rates we had,” Kent said. “But even at slower rates [of subsidence] this is still a critical issue going forward.”

The slides show that the highest rates of sinking afflict communities protected by levees, New Orleans among them.

Once levees are raised on deltas, the land inside begins to drain, causing them to subside more rapidly than surrounding wetlands. This leads to compaction, triggering more rapid decomposition of some soil types.