If you’re developing one of the largest river management projects in the world — an initiative with social, economic and political challenges — where do you look for help?

Well, everywhere.

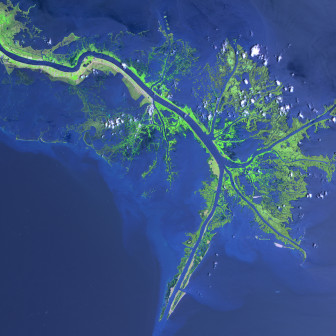

That’s the idea behind the Changing Course competition – a call made to the world in September from Louisiana offering $400,000 for ideas about how to maximize the Mississippi River’s ability to rebuild the wetlands south of New Orleans, while also meeting “the needs of navigation, flood protection and coastal industries and communities.”

Twenty-one teams with members from 23 states and seven countries responded by November. That group has now been pared to a semifinal group of eight.

By April, two to four teams will receive funding to fully develop ideas that could be included in the 2017 version of the state’s Master Plan for the Coast.

So why is Louisiana looking for ideas when it already has a 50-year, $50 billion blueprint to achieve the same goals as those outlined in the competition?

Steve Cochran of the Environmental Defense Fund, which is helping manage the process, says the answer is simple: Picking the best brains in the world is never a bad idea.

“The competition isn’t saying the ideas in the plan aren’t good ones,” he said. “These competitions are used when you have a project of this significance because everyone agrees, the more eyes you have on a challenge, the better the result.”

The goal is to spur ideas that have “the engineering and design quality” as well as the involvement of stakeholders, such as the shipping and fishing industries and coastal residents.

The competition is a public-private effort developed by a 17-member leadership team that includes representatives from the state, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, university and private sector researchers, and stakeholder groups.

“Other parts of the world are facing the same problems we’re challenged with here – including sea level rise – so we’re hoping this exercise will also showcase the expertise we have on addressing those problems.”—Steve Cochran, Environmental Defense Fund

The applications and designs are being reviewed by a 12-member technical team, which is working with the leadership team.

The competitors will have access to technical data already collected by the state and the corps, and they can consult with a stakeholder team.

Cochran said the leadership team has not been surprised by the enthusiastic interest from some of the world’s top engineering firms. Louisiana’s problems on its southeast coast are similar to those being experienced on deltas across the planet.

“Part of the attraction was that in this case, Louisiana is ahead of the rest of the world with the Master Plan,” he said. “If this is the sort of work they do, then this is where they want to be. They want to be part of this design initiative to demonstrate their capacity to think about solving these kinds of problems, which will be an advantage in competitions going forward.”

Cochran said organizers hope the competition will provide a boost for the state’s technology industry.

“Other parts of the world are facing the same problems we’re challenged with here – including sea-level rise – so we’re hoping this exercise will also showcase the expertise we have on addressing those problems,” he said. “By showing the world what we can do — by making plans concrete, we’ll be able to market that expertise and have an economic payback in the future.”

Entering the competition involves financial risk because the teams must bear all the costs of their proposals. Only the finalists receive a part of the $400,000 to develop their ideas.

Cochran said funding comes from the Rockefeller Foundation, Blue Moon Fund, the Kresge Foundation and the Selley Foundation, which is administered by the Greater New Orleans Foundation.*

Teams advancing to semifinal round

*Correction: This post originally stated that one of the funders of the competition was the Rockefeller Family Fund, but it’s the Rockefeller Foundation. It also omitted the Kresge Foundation. (Dec. 12, 2013)