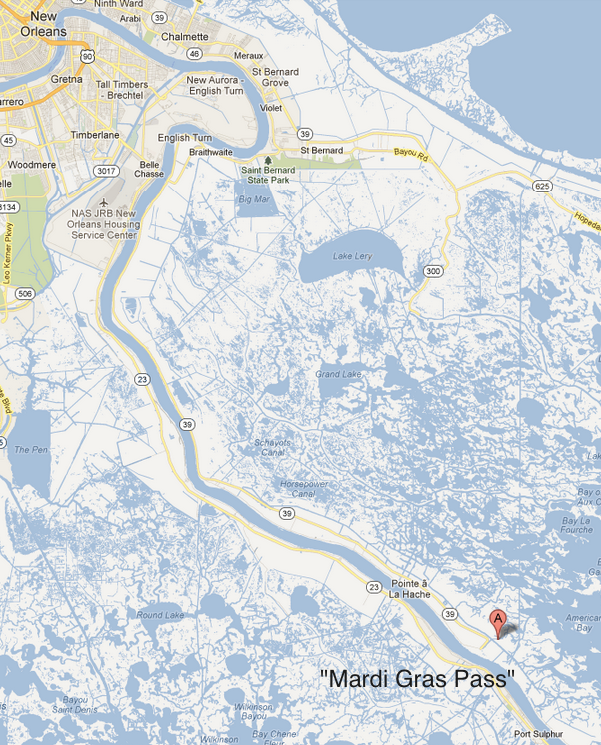

Thirty-five miles south of New Orleans, the silt-laden Mississippi River intermittently rolls through a 150-foot gap that started opening on the river’s east bank during the Mardi Gras 2011 flood. The café-au-lait water rushes noisily through the channel it carved across an adjacent shell roadbed, then sweeps eastward toward marshes spreading to the horizon.

To John Lopez of the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation, it’s a miracle in the making, a coastal restoration project at zero cost to taxpayers. “Mardi Gras Pass,” as he’s dubbed it, reconnects the Mississippi to a landscape that’s been starving and sinking since levees blocked the river’s annual sediment delivery almost 80 years ago.

To Robin McGuire, a vice-president of Dallas-based Sundown Energy, it’s a costly business interruption that has severed road access to a nearby oil and gas field his company had enjoyed for six years.

And to the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, which supports closing the new pass at least temporarily — even though its mission is to restore the coast vanishing wetlands — it’s a perfect example of why its job is never as simple as it seems.

“Putting the river back into the marsh is a central theme of the state’s Master Plan – something we will be spending billions to achieve,” Lopez argues, alluding to the state’s $50 billion, 40-year strategy for battling rising Gulf waters.

“Here we have a diversion that has been given to us by the river — for free,” Lopez continues. “Why would we want to turn down that gift? How can anyone be against that?”

That’s a question that will be asked more frequently as the state moves forward with its Master Plan for the coast. The answer is almost always complicated.

It’s well nigh impossible to find anyone opposed to the idea of “coastal restoration.” Storms like Katrina, Gustav and Isaac have shown individuals as well as powerful industries the value of the marshes and swamps that once stood between them and the Gulf.

But when “restore” means turning things back to the way they once were, problems can arise.

That’s because Louisiana’s coast is hardly a wilderness. For more than 100 years its wetlands have been a tidal seafood factory and an oil and gas field where varied interests made comfortable, sometimes huge, livings harvesting its bounty. And as those industries helped push a healthy ecosystem to the brink of collapse — turning nearly 2,000 square miles of wetlands to open water — they protected their profit margins by adapting to those changing conditions.

So restoring some locations to the conditions that prevailed even 60 years ago can mean extra expense, displacement or going out of business.

The best known conflicts have involved oystermen, shrimpers and some sports fishing guides, groups that have fought river diversions. Why? Because an influx of fresh river water pushes out the targeted saltwater species that conveniently have crept closer and closer to the mainland over the years.

For its part, the shipping industry worries about changes in the depth of the river and the positioning of sand bars as diversions alter river currents.

Developers hoping to build a giant new coal terminal near Myrtle Grove find themselves in the path of a congressionally approved diversion.

And oilmen like McGuire, who say they support the rebuilding of shrinking wetlands, can suddenly face new expenses and controversy — as is now happening at Mardi Gras Pass.

McGuire’s company, Sundown, purchased what is known as the Potash Field in 2002, and for the next three years accessed the facility the way its previous owners did, by boat along what is known as the Back Levee Canal. But after Hurricane Katrina struck, Sundown says it bought the right-of-way to the abandoned shell road and started using it to clean up an oil spill and rebuild its facility.

The road extends about four miles south from the end of Louisiana Highway 39 just south of Pointe a la Hache, the endpoint of the federal Mississippi River Levee on the east bank. It crosses the Bohemia Spillway, built in 1926 to bleed volume from the Mississippi when high water threatened New Orleans.*

Bohemia’s value and active operation ended in the early 1930s after the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers built the much larger Bonnet Carre Spillway upriver from New Orleans. However, the river has continued to flow intermittently over Bohemia’s natural bank and into adjacent wetlands, creating Mardi Gras Pass.

That’s one reason the wetlands habitat in the Bohemia flow path are much healthier than others in the area, Lopez said, showing visitors the mixed hardwood forests that extend a good quarter mile from the river bank before giving way to miles of marsh filled with tall grass and cane.

“That’s one reason Mardi Gras Pass excites us. This is the perfect laboratory to study the effects of a diversion.” — John Lopez, Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation

And that convinces the lake foundation and several other organizations, as well as the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East*, that Mardi Gras Pass should stay open.

“The plant community is more diverse and healthier here, and there’s a greater elevation because of the help this area gets when the water and sediment is flowing through Bohemia,” Lopez said.

“That’s one reason Mardi Gras Pass excites us. This is the perfect laboratory to study the effects of a diversion. And it’s been set up for us by the river, at no cost to the state.”

It hasn’t been cost-free for Sundown.

McGuire estimates accessing the site by road is about $12,000 a month cheaper than using boats, as well as being faster and more convenient.

No one seemed to notice or mind that benefit until his company filed a permit to close the newly opened crevasse and rebuild the collapsed road bed, using two 72-inch culverts to allow some flow into Bohemia when the river overtops the bank, typically during the spring.

Coastal advocacy groups objected, pointing to studies by the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation showing that the culverts would restrict flow by as much as 80 percent.

“Our study shows that at the high water like we had in 2011, the flow through Mardi Gras Pass could be as much as 5,000 cubic feet per second,” Lopez said.

Using projections for other state-planned diversions, Lopez said his group estimates the natural and wild Mardi Gras Pass could build 1,000 acres of new land over fifty years.*

The lake foundation rallied support from a long list of coastal groups, as well as the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, urging the state Department of Natural Resources to reject Sundown’s permit request, and calling for a pubic hearing, now set for 6 p.m. March 20 at the Belle Chasse Auditorium, 8398 La. 23.

Sundown can’t be accused of refusing to cooperate. At the suggestion of the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, it amended its original plan from two culverts to four. And when coastal groups suggested a bridge over the opening instead of a road, Sundown pledged $325,000 toward the cost, which the lake foundation estimates would be about $2 million.

Lopez points out that $2 million is far less than the $200 million or so the state might spend for the Lower Breton Sound Diversion, planned a little more than a mile south of Bohemia. The state estimates that the diversion would sluice water into the marsh at a rate of 50,000 cubic feet per second and build 9,000 acres in five years.

“Mardi Gras Pass could end up meaning the Lower Breton Sound project could be smaller, and cost less money,” Lopez said.

But just as Mardi Gras Pass supporters were beginning to think a “win-win” had been found, the coastal restoration authority threw cold water on the compromise.

Once again, it turns out coastal restoration isn’t as simple as it sounds.

“We expect to have more diversion capacity than excess water available in most years. Hence, the investment of that resource needs to be properly managed.” — coastal restoration czar Garret Graves.

Letting the river go wild, as many coastal advocates have been urging for years, is no longer feasible, said Garret Graves, head of the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority. The Mississippi may be the third-longest river on the planet, but claims on its water — and a sediment load that has been greatly reduced by upstream dams — now must be carefully rationed, even as much of Louisiana’s southeast coast faces its life-or-death crisis.

“The ‘water budget’ of the Mississippi River is limited,” Graves wrote in email exchanges. “There is a certain amount that is needed for navigation, managing the saltwater wedge and other issues. The water that is in excess to those core needs is what we have to use for our diversions.

“We expect to have more diversion capacity than excess water available in most years. Hence, the investment of that resource needs to be properly managed. The diversions need to be operated in concert as part of a larger diversion strategy. We likely will not be able to afford to use water outside of the controlled structures in most years.“

Those increased water demands helped guide the authority’s selection process for tentative large-scale sediment diversions, Graves said. Other factors included the amount and type of available sediments and the timing of those availabilities, given the river’s courses and currents.

And when the authority’s engineers looked at Mardi Gras Pass, they recommended Sundown’s closure/culvert route while they studied its future, because the financial risks of letting it go wild were too high if it needed to be closed later, Graves said.

“We are on board with the proposed approach [closing and culverts] because it buys us time to develop a long-term solution,” Graves said. “The culverts are not a long-term solution, but they do prevent the area from further eroding.

“If we later determine that Bohemia is not the right alignment, we would be spending tens of millions of dollars filling the growing hole created by the uncontrolled diversion.”

And that can be expensive, Graves cautioned. “The lesson learned from West Bay [a controversial uncontrolled diversion south of Venice,] is that you don’t do uncontrolled diversions.” Graves estimated the cost of closing the West Bay at $30 million to $50 million, “depending on how you calculate.”

Graves added, “Our efforts will be focused on investing our ‘water capital’ to ensure the largest return on that investment or the biggest ‘bang for our buck.’ ”

To Lopez and others, Graves’ thinking runs counter to the state’s more urgent priority: building as much land as possible as quickly as possible.

“However long Mardi Gras Pass remains closed, we’ll be losing the opportunity to build land and improve wetlands in the Bohemia area,” Lopez said.

For Tim Doody, president of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, which believes its job is aided by the addition of wetlands, the decision is clear.

“To approve this roadway to seal off the river from the marsh yet again, makes us look like we say one thing but do another,” he wrote in a letter to the Department of Natural Resources, noting that his agency, the state and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers all embrace the idea of reconnecting the river to the marsh.

Graves said his office has heard the complaints.

“We’ve received some concerns from the environmental community on this approach and plan to engage these folks to see if there is something that we’re missing,” he said by email. “We’re certainly open-minded on this. If the opening of the crevasse provides a good opportunity, we want to take advantage.”

The decision will be made subsequent to the March 20 hearing. But as with most issues in Louisiana’s coastal restoration struggle, the differences of opinion aren’t likely to end there.

*Corrections: The Bohemia Spillway was created in 1926; the story originally said 1927. Further, Lopez said the natural opening in the river could create 1,000 acres of land in 50 years, not five years, as the story first read. The name of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority – East was misstated in the original version.