Operation REACH, Inc., the troubled education nonprofit, failed to properly account for nearly $900,000 in grant money received over three years, some of which may have been misspent, according to an audit by the federal agency that awarded the cash.

The New Orleans-based nonprofit’s questionable spending was “unsupported by required documentation and/or incurred improperly,” according to the Inspector General’s Office of the Corporation for National and Community Service, one of Operation REACH’s main funders.

The nonprofit’s poor financial management and improper recordkeeping were “so alarming,” in the view of federal auditors, that they sent a warning to the Corporation for National and Community Service before the audit was complete. The corporation then froze Operation REACH’s grants, and at least one state branch of the federal agency terminated its grants.

Operation REACH has earned acclaim over its 13-year history with programs offering tutoring, mentoring and college counseling for children and teens. The organization also served as a conduit for hundreds of AmeriCorps employees who worked for 36 partner organizations.

The Corporation for National and Community Service is the parent organization for AmeriCorps.

The audit comes nearly six months after a Lens investigation revealed that thousands of dollars from the nonprofit’s coffers were spent at restaurants, vacation destinations and apparel stores. In that article, former employees raised concerns about what they called extravagant spending by founder and Chief Executive Officer Kyshun Webster.

In July, Webster went public with a document from the inspector general’s office announcing that its initial investigation was closed. At that time, Vincent Mulloy, general counsel for the inspector general, declined to comment on findings from the initial investigation, citing privacy concerns and law enforcement’s involvement in the case.

The audit includes Webster’s responses to the findings and explanations of his spending.

Webster declined to be interviewed by phone for this story, though he answered questions from The Lens by email.

He wrote that neither he nor the organization did anything wrong. He cut the financial ties to AmeriCorps, he reiterated. The inspector general disputes that contention.

“It is important to note that there were no findings of criminal wrong-doing or fiscal misconduct in this audit,” Webster wrote.

Payroll records missing

The audit centered on improper payroll records and insufficient documentation to back up expenses, said Stuart Axenfield, assistant inspector general for audits with the federal agency.

“The bulk of the questioned costs were just the complete lack of support,” Axenfield said in an interview. “They are required to keep timesheets to show that they worked on our grants. We have no evidence that these people worked on our grants.”

Axenfield referred to laws that require federal grantees to closely track costs of fulfilling program objectives. Without proper timesheets and detailed descriptions of what employees were doing, a grantee can’t prove it spent the money properly.

The Corporation for National and Community Service has funded Operation REACH for at least the past three years. The nearly $900,000 in question is a portion of $2.5 million that AmeriCorps gave the nonprofit from June 2008 to September 2011, money that was intended to advance programs at Operation REACH offices in Louisiana, Georgia and Alabama.

Time line in dispute

In a March interview, Webster said he severed financial ties with AmeriCorps because it was slow to reimburse him for expenses and because “politically uncertain times in Congress” made it a shaky source of future financing. A spokeswoman for the Corporation for National and Community Service rebutted Webster’s claim, saying that the agency suspended payments to Operation REACH after finding “irregularities.”

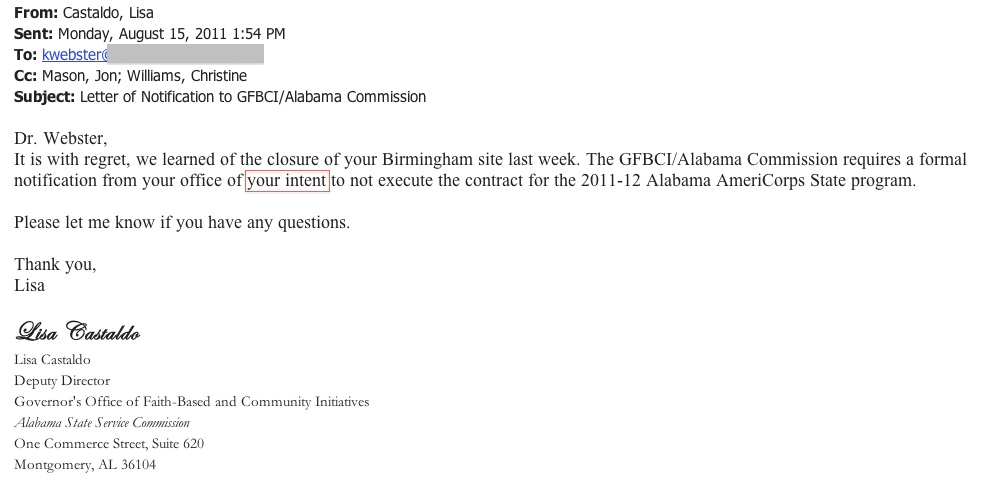

A time line included in the audit confirms that the agency’s Georgia office withdrew its grants, and grant agreements with Operation REACH offices in Alabama and Louisiana were not renewed after coming to an end in September 2011. Webster provided emails in July, written last year, that he said proves that he declined to take further funding from the Corporation’s Alabama office after deciding to end Operation REACH activities in that state. He did not provide information regarding the end of his relationship with the Louisiana office.

Key findings detailed

Here are the major findings from the audit, released Aug. 28:

- Operation REACH spent $349,469 of federal grant money on unallowed and improperly documented items. The organization also failed to provide supporting documentation for in-kind contributions that Operation REACH used to match a portion of the federal grants.

- Auditors said the organization failed to provide proper timesheets for its employees and for AmeriCorps employees, throwing into question $369,279 in government funding.

- The organization couldn’t account for $121,521 in service fees it received from its 36 partner organizations that Operation REACH used to match a portion of the federal grants.

- The organization failed to perform criminal background checks and provide other eligibility documents for at least 21 AmeriCorps employees, resulting in AmeriCorps employee ineligibility and putting $31,529 in question.

- Finally, the organization tasked at least one AmeriCorps employee with a job that didn’t fall in line with job descriptions. The improper work included caring for children in the organization’s for-profit daycare, The Knowledge Garden. The improprieties put the cost of that employee’s compensation – $15,047 – in question.

In total, the Office of the Inspector General determined that Operation REACH couldn’t properly account for $886,845. Auditors recommended that the corporation disallow and recoup $538,035 in federal money, and it recommended that Operation REACH provide supporting documentation for $121,521 in partner organization service fees. It also recommended that the federal agency analyze $227,289 in questioned match costs.

The corporation has until Feb. 28 to review the auditor’s recommendations and make its decision, and no later than Aug. 28, 2013 to complete any corrective actions required of Operation REACH.

Samantha Jo Warfield, a corporation spokeswoman, said Thursday that it will ask Operation REACH to properly document expenses.

“We will work with the inspector general to determine the most appropriate way to continue to hold Operation REACH accountable,” she said.

The nonprofit’s response

Operation REACH’s response, signed by Webster, agreed that its payroll practices included improper documentation. He urged the corporation to work with Operation REACH to obtain affidavits of work performed from each employee in question. He disagreed with all other findings.

In an email to The Lens, Webster did not respond to questions about the central finding: that $350,000 was spent on improper purchases.

He said the organization would be working with the government to resolve the issues auditors raised. He stressed that the findings are one step in a “process.”

“We cannot predict the outcome of negotiating any of the questioned costs. Despite any questioned technical rules of execution, Operation REACH, to the best of its ability, stood up to serve tens of thousands of children and youth serving organizations across the region post Hurricanes Katrina and Rita,” he wrote.

He also noted that the final decision on how to resolve any audit findings is the national agency’s decision, not the inspector general’s.

Inappropriate expenditures noted

Axenfield said that in examining the corporation’s expenses, auditors found seemingly inappropriate expenditures such as those discovered by The Lens in its examination of Operation REACH bank statements in March: resort visits, restaurant charges, and other expenses hard to square with the nonprofit’s mission.

“But we couldn’t see if those were charged to our grants,” Axenfield said. He noted that Operation REACH could have been paying for such expenses out of its own revenues, or with cash it received from other donors. The major issue, he said, was the lack of documentation to prove that the nonprofit spent taxpayer dollars on what it said it would and matched the amount it agreed to.

In his response to the audit, Webster parried Axenfield’s criticisms by saying that the inspector general could have contacted Operation REACH’s partner organizations to get the needed information. Webster asked for more time to get that information himself.

Operation REACH was required by AmeriCorps to match 24 percent of each grant awarded, Webster said in an exchange with The Lens. That 24 percent could be matched in actual dollars or through in-kind donations, such as office space used for the nonprofit’s programs, or time spent working on those programs. The organization outsourced much of the match to partners where it had placed AmeriCorps employees.

The problem, auditors said, was a lack of due diligence by Operation REACH in acquainting itself with federal grant laws. Federal grantees are required to track all supporting documentation for in-kind costs, including in-kind match costs. Supporting documentation for in-kind costs can include determining the fair market value of rented space or written confirmation of the salary of an employee tasked to work on that program. That information was lacking, Axenfield said.

Webster also disputed the finding that the organization improperly spent its partners’ match dollars, known as service fees. He said improper documentation resulted from administrative errors that could be remedied with more time.

Auditors said Webster had had multiple opportunities during and after the audit to provide the federal agency with all the documentation it needed.

“By failing to demonstrate how it included the AmeriCorps members’ service fees to expand the programs, [Operation REACH] may have benefited by receiving funds [to] which it was not entitled,” the report reads.

Auditors also said that the nonprofit consistently failed to follow proper procedures. Moreover, providing adequate supporting documentation was the responsibility of Operation REACH, not its partner agencies.

Regarding the failure to do required background checks, Webster blamed the national agency for not coordinating that process with the FBI’s fingerprint check program. He did not respond to the auditor’s contention that none of the organization’s AmeriCorps employees had high school diplomas on file, as required.

Although not directly funded by the Corporation, Operation REACH’s daycare, The Knowledge Garden, was recently recommended for revocation of its license by state child welfare officials. Here, too, the issue is a failure to perform employee background checks.

Finally, in his response to the auditors’ claim that an AmeriCorps employee was improperly assigned to work in Operation REACH’s daycare facility, Webster said those job descriptions were created to meet Operation REACH’s organizational needs and were approved by the Corporation.

The organization’s overall response was headed by a disclaimer that assigned responsibility for the AmeriCorps program to former chief compliance officer Nicole Payne-Jack, who questioned Webster’s spending before leaving the organization.

Payne-Jack told The Lens that she did her job to the best of her ability, within the limits of her authority. She said Webster’s effort to pass the buck doesn’t hold up, given that as CEO, he has final authority over spending.

“I don’t understand how he could even make a disclaimer on how I had control over those things, because I never had control of the finances,” Jack said.

“Programmatically, I could train my employees on how to run a background check, but if we didn’t have the money to run those background checks, or if we didn’t have access to the money, then how could you be compliant?”

In his email to The Lens, Webster said that Payne-Jack “was given all rights and executive privilege to control these finances and had a credit card that could be used exclusively for expenses related to the program.”

In the same paragraph, however, he wrote that Operation REACH believes Payne-Jack “did her job to the best of her ability and with limiting constraints from [AmeriCorps]. Given her diligence with managing the grant since its [inception], some of the OIG’s findings caught [us] by surprise.”