By Karen Gadbois, The Lens staff writer |

It’s a 19th century house significant enough to have attracted a state Historic Building Recovery Grant of $45,000. And that was on top of $135,000 in Road Home money, plus another $20,000 grant from the Arab emirate of Qatar.

But today, with only minimal work to show for all that money, the Greek revival house at 2013 Dumaine Street has been slapped with a city demolition order, and Treme neighbors wonder if ongoing removal of old brick, timbers and architectural detail might lead the structure to collapse even before the bulldozers show up. The dismantling continues in defiance of a stop-work order slapped on the property.

The chain of events leading to the likely demise of yet another architectural gem is a tangled tale of botched rehabilitation efforts and seemingly little follow-up on how government grants for recovery and preservation are spent.

As early as 1946, l’Hote Townhouse – to give the residence its proper name – was identified in a city inspection report as “out of plumb 2 feet,” meaning the structure was starting to tip over. And the need for further remediation was noted in 2000 when the house was designated a landmark.

Efforts to save it intensified in early 2003. Owner Rod Lindauer, a local artist, occupied a small portion of the upstairs with his wife as they set about rehabbing a house that was falling down around them.

Termites had invaded the side of the house built of wood, but a wall of solid brick was structurally sound, Lindauer recalls.

Overwhelmed by the scope of the work, in 2004 the Lindauers sold the place to New York real estate investor Coy LaSister for $55,000.

Katrina likely worsened the subsidence that was tipping the house, Lindauer said, but on his visits to the place after selling it, he saw no sign that repairs were under way.

Neighbor Will Germain got the same impression. Now and then LaSister would come by and hang potted plants but, so far as Germain could tell, the new owner never spent a night in the house. To Germain it looked like an open-and-shut case of “demolition by neglect.”

Messages seeking comment from LaSister were intercepted by a brother who said he is ill and in a nursing home.

The definitive study of the area’s housing stock, “New Orleans Architecture: Fauborg Treme and the Bayou Road,” describes the circa 1860 residence as a two-story Greek revival townhouse with significant iron work, the “major decorative element” on an otherwise “extremely restrained” façade.

After Hurricane Katrina, LaSister applied for and received funding to stabilize and renovate the property.

The $45,000 Historic Building Recovery Grant was awarded in March 2007. Work began but records on file with the state are spotty and in some instances were submitted past deadline or seek reimbursement for ineligible expenses, such as scaffolding, according to documents obtained by The Lens through a public records request to the state.

According to the contract LaSister submitted to the state, the work was being done by TH Montano General Contractors LLC, with a “principal place of business” on St. Claude Avenue.

Louisiana’s Secretary of State website shows no listing for TH Montano General Contractors in New Orleans, though there is a TH Montano Construction in Baton Rouge.

Lisa Batiste Swilley owner of the Baton Rouge business denies doing work on the Dumaine Street property but acknowledged that she has done work in the past with Tracy Williams, who eventually bought out LaSister and is now the owner of the beleaguered mansion along with David Taffet, her business partner on several real estate projects.

The New Orleans property assessor’s website lists Taffet’s home outside Philadelphia as the mailing address for Dumaine 2013-2017 LLC. The Secretary of State’s website calls Williams the LLC’s manager.

According to a letter written by Coy LaSister’s brother, Knox LaSister, an extension for the historic preservation grant was requested and approved, pushing the completion deadline back to December 2008.

In the letter submitted to the state, Knox LaSister said the contractor was “overwhelmed by the scope of the work” and subsequently fired.

LaSister went on to explain to state officials that a new contractor had been identified as well as additional funds from The Road Home and the Qatar Foundation’s $20,000 grant, which was to redo the roof. LaSister then requested a further deadline extension, to May 2009.

In February 2009 LaSister was awarded the Road Home grant of $135,000. But in April 2009, the state partially withdrew the historic preservation grant. LaSister was forced to return $11,150 but was permitted to retain $7,000 as reimbursement for some early site-prep work. The rest of the $45,000 had not been spent.

In May 2009 LaSister sold the property and, by covenant written into the title, the obligations to rebuild the house with the grants received passed to the new owner, 2013-17 Dumaine LLC.

Williams, who owns numerous properties in the area, says she believes an earlier permit for repairs, issued in July 2011, is all she needs to continue the work; the city disagrees. On March 22, inspectors declared the house in imminent danger of collapse and issued a demolition permit.

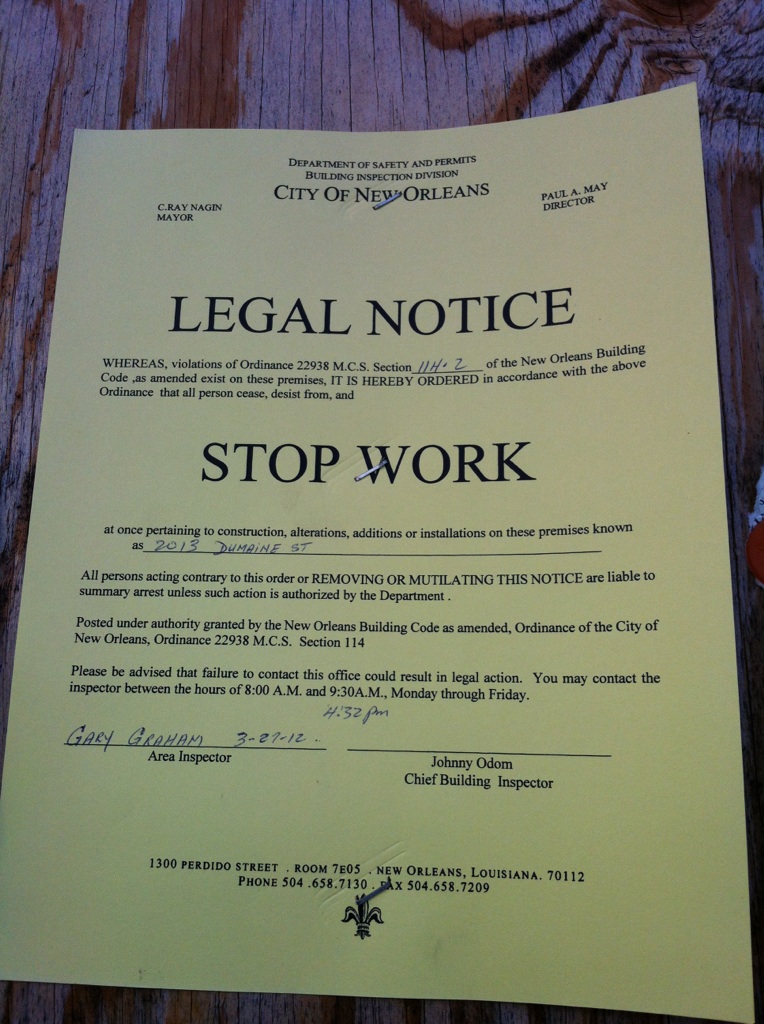

Four days later, the city issued a stop-work order.

According to neighbor Will Germain, workers have been on site in recent days hauling away the bricks, in defiance of the stop-work order.

Williams contends the brick is being removed only temporarily and will be returned to the site as part of the restoration she plans.

Christina Stephens, communications director with the state Office of Community Development, the agency overseeing Road Home grants, declined to speak about individual cases but made clear that an owner who buys a property that has been awarded rehabilitation grants is responsible for completing the work.

“The new owner who accepted the covenants would be bound by the same timeframe for rebuilding and re-occupancy,” she said.

In the case of this property the deadline was February 2012, Stephens said.

She added that LaSister’s eligibility for hurricane recovery grants hinged on his being the owner/occupant of the property when Katrina struck, not just someone who came around from time to time to hang potted plants, as neighbors allege.

“If we suspect that this was not the case and the program had been misled by the applicant, certainly we would investigate the situation for potential fraud,” Stephens said.

Germain assumes the 150-year-old house is doomed. As he watched a laborer hauling off a wheelbarrow of ancient brick recently, his only question was whether removal of structural materials will cause the building to collapse even before the city demolition order can be executed.