And so, Gen. Robert E. Lee has been toppled from his shaft and hauled away like an empty float after a Mardi Gras parade. The fourth and most prominent of the “Confederate monuments” is history.

No doubt the statues will crop up again some day, in what one hopes is a more appropriate setting — a museum of some sort, perhaps a museum of slavery. And maybe the pedestals where they stood will eventually get new tenants, more up-to-date heroes. But for the moment, maybe for a good long while, I’d propose that we leave the four sites just as they are: statue-less, partly reduced to rubble, like the base of the Beauregard statue at the entrance to City Park.

Why leave the empty pedestals in place? Because the fight to remove the monuments has been as significant as any episode in the politics that has swirled around these things during the century-plus since they were erected. No less than the Civil War itself, the fight to remove the monuments is now part of our “heritage,” to use a word popular with folks who were rabidly opposed to bringing them down. It is a chapter in our municipal history.

If we need to put up plaques contextualizing the empty pedestals, so be it. “Contextualizing” will be recognized as another word popular with the pro-monument crowd — as though a little more ‘splaining would have made monuments to white supremacy in a 21st-century American city less obnoxious allocations of public space.

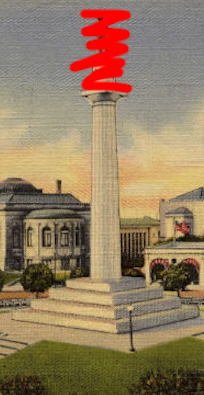

Until Lee came down and New Orleans got its first close-up of the tiny figure atop the towering pedestal, it was impossible to see, other than by drone, what an embarrassingly artless manikin had been erected to venerate him.

Lee stood over Lee Circle — still called “Tivoli Circle” on city plats — playing two roles: He was a relic of the 15 months during which New Orleans was under Confederate rule. More potently, he was an omen of the much longer period of legalized racism that followed Reconstruction and began to fall apart with desegregation 80 years later.

Why Lee? Even a more inspired rendering would beg the same question. Why such a prominent monument to a 15-month interlude in New Orleans’ long history? Why not a monument to the Union soldiers who camped at Tivoli Circle, the ones who liberated a city where Lee never fought? (Just kidding.) Why not a monument to the millennia during which Native Americans held sway over this same turf?

Tired of politics? OK. How about topping that pedestal with a really fabulous, geo-specific icon — a gator or pelican or a cockroach, perhaps in the spirit of the Louise Bourgeois spider in the Besthoff Sculpture Garden at City Park. Art lovers would flock to see it from around the world. A cop-out? All right, let’s cut to the very heart of Southern history and build a brutalist monument that shows an enslaved black man throwing off his chains.

Just as the preservationists feared, New Orleans was not the same place Friday evening that it had been the day before.

When it comes to city monuments and other acts of public veneration, we have choices to make, and we better make them wisely. Because history always tells at least as much about the present as the past. It also tells a lot about the historian.

I’ll put my cards on the table. As the Duck Dynasts among you will have figured out by now, the author of this column is not a good ole boy. Slaveholders don’t lurk in the branches of my family tree. I’ve lived here for a quarter century but will always be an interloper from up North, a carpetbagger. (Hey! How about a monument to carpetbaggers?) My people made misery and money running copper mines in Cuba and converting the young men of China, where my mother was born, into agents of the American imperium.

My great-great-grandfather didn’t own slaves. He inveighed loudly and eloquently against slavery from his pulpit in Litchfield, Connecticut, in those days a town of significance to more than just rich New Yorkers looking for stylish weekend homes.

He scolded the men of his congregation. He said they should be ashamed of their cold feet, their fear that going to war to save the Union might jeopardize profits from the triangular trade in sugar, rum, coffee and captive Africans. He exhorted their sons to enlist in the fight against secession and slavery and then risked his own life by venturing to the Virginia battlefront to bring spiritual comfort to Union soldiers who had answered his call to arms. Other kin of mine died on the battlefield fighting the rebels.

In guiding the iteration of our history now enshrined in statue-less pedestals, Mayor Mitch Landrieu upheld personal beliefs and a political family’s multi-generational opposition to racial barriers. He was wise to secure majority support from the City Council.

There was no referendum; some had argued for one. I think we can be grateful that they failed. Democracy has its own logic, and sometimes the distancing mechanism embodied in representative government — as opposed to governance by plebiscite — is exactly what’s needed.

If you think the run-up to removing the monuments was racialized and ugly, try to imagine what the past couple of years would have been like if we had spent them in the teeth of a referendum fight funded by the likes of Frank Stewart. And now try to imagine if, one way or another, the pro-monument crowd had managed to prevail in the retention of shrines to white supremacy in a city with a majority black population.

Just as the preservationists feared, New Orleans was not the same place Friday evening that it had been the day before. There was a change in the air, a welcome one. It was like a weight had been lifted off the city after more than a century in the shadow of clumsy monuments to a military fiasco and the legalized Jim Crow racism imposed by whites suddenly scared of their former slaves.

If common sense prevails, the people of New Orleans will make sure the Lost Cause crowd fulfills its glorious heritage and loses once again.

The feeling of liberation was nowhere more beautifully expressed than in media images of beaming young black men trying to shake hands with the camo pants and battle flag crowd, the folk who had jeered and menaced them. Some of the wannabe Johnny Rebs even got pulled into awkward embraces by the victors.

The tables had turned. Blacks were showing whites — allies and foes alike — a cross-racial graciousness that can be modeled only by people who have known oppression, not just opposed it. Black New Orleans, the parts of it not too downtrodden to feel the change, radiated ebullience. It was as if African-Americans had finally taken title to a city in which they have been a demographic majority for a couple of generations.

Of course there will be relapses into racial foolishness.

No doubt New Orleans-based writers of liberal persuasions will continue to hunch over their laptops and confide to the world our dirty little secret: that racism still lurks beneath the Big Easy veneer — as if racism were any more persistent in New Orleans than in Boston or Chicago or Baltimore or New York.

No doubt the diehards will raise a clamor one day to resuscitate the mothballed statues. If common sense prevails, the people of New Orleans will make sure the Lost Cause crowd fulfills its glorious heritage, as losers yet again.

Symbols are important, but maybe it’s time to move beyond this particular batch of them and focus on a more urgent and difficult agenda: overcoming structural inequities apparent not just at a traffic circle, a neutral ground and at the entrance to a public park, but all across the city’s economy and criminal justice infrastructure.

Meanwhile, get out your cameras, your folding lawn chairs, your ice chests and join me at Lee Circle in contemplation of that empty pedestal. It speaks eloquently of a moment in our history, a moment — maybe no more than that — when “heritage” lost its hold on hate.

Jed Horne’s book “Desire Street” dealt with a Louisiana death-row case. He was awarded a Pulitzer Prize as part of the team covering Hurricane Katrina for The Times-Picayune.

Views expressed in the Opinion section are not necessarily those of The Lens or its staff. To propose an idea for a column, contact Lens founder Karen Gadbois.