As he looked at the amount of money coming to Louisiana from BP’s settlement of the Deepwater Horizon pollution disaster, David Muth shook his head in wonder. He saw tens of millions going to rebuild dolphin populations, hundreds of millions for birds and fish and — best of all — billions for restoring coastal wetlands.

“Those are figures we could only dream about before BP,” said the head of the National Wildlife Federation’s coastal effort here. “Sums like these for the coast are almost unbelievable.

“I mean, we’re talking billions,”

They’re talking as much as $8 billion. And what makes that figure especially pleasing to coastal advocates is that two of their overriding wishes for the final settlement appear to have been realized.

First, federal rules governing the spending ensure most of the money will be used for ecosystem restoration, not economic development. That allays long-held fears the big payday would set off a feeding frenzy among politicians for projects unrelated to the coast.

And second, Louisiana’s cash-strapped Coastal Master Plan — the state’s last, best hope to save its sinking coast — will be the biggest winner, getting at least $4 billion.

BP’s final bill came to $20.8 billion. Nearly $6 billion of that is set aside to address economic damages to cities and states. The remaining $14.9 billion is primarily going to environmental restoration, and the spending is guided by a federal settlement.

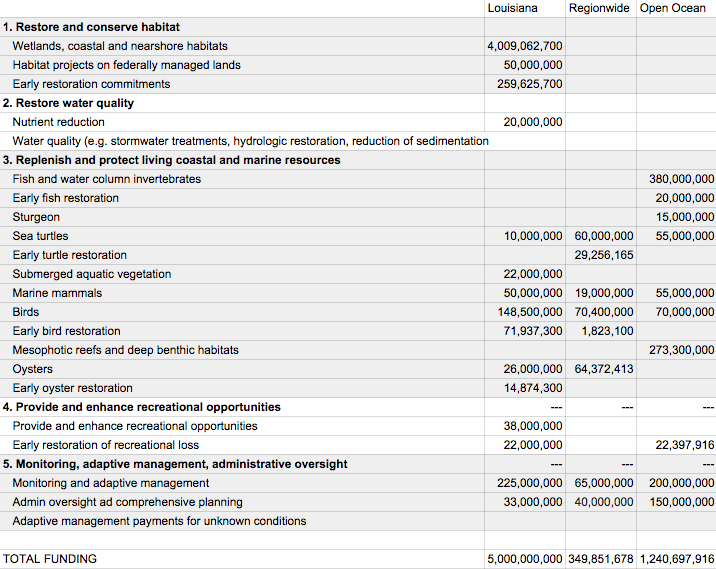

This is how Louisiana’s $8 billion share for coastal damage breaks down and how it will be used.

Natural Resources Damage Assessment: $5 billion

The single largest award to Louisiana from the oil spill is also the best news for the master plan. The Natural Resource Damage Assessment, required by the Oil Pollution Act, is a tabulation of the animals and habitat harmed by the pollution as well compensation to the recreational fishing community for lost fishing days.

The law says these payments can only be used to repair those damages, and the settlement spells out how much money must go to each of the different losses. The rules and oversight in place for spending the funds can be found in Appendix 2 of the settlement.

Here’s how Louisiana must spend its $5 billion award for resource damages.

The coastal master plan is the big winner because $4 billion must be used to “restore and conserve” wetlands, coastal and near-shore habitats in Louisiana — which is a main goal of the plan.

Kyle Graham, head of the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, said projects in the master plan will easily qualify for funding under the settlement.

All projects developed by the states must be cleared by the federal government and then presented for public comment before final approval. The state is only beginning the application processes for most of the spending categories, Graham said, but listed the following master plan projects likely to get some of the funds:

- New Orleans East Land Bridge Marsh Creation

- Lake Borgne Marsh Creation

- Pass-A-Loutre Restoration

- Barataria Basin Ridge and Marsh Creation

- Terrebonne Basin Ridge and Marsh Creation

- Mid Barataria Diversion

- Raccoon Island

- Wine Island

- New Harbor Island

- Queen Bess Island

- Cat Island / mangrove islands

- Rabbit Island

- Freshwater Bayou Shoreline Protection

The Department of Wildlife and Fisheries has already announced plans to use some of the money for a $48 million Louisiana Marine Fisheries Enhancement and Science Center, which will include fish hatcheries, aquaculture research and enhancement, and education and science facilities.

Criminal settlement: $1.3 billion

Louisiana can use this funding only for barrier island restoration or river diversion projects. About $220 million has so far been released to the state for those purposes. That figure likely will jump soon with the recent approval by the state to build the Mid-Barataria and Mid-Breton Sound sediment diversions.

Clean Water Act: $929 million

Environmentalists rejoiced when Congress passed the RESTORE Act because it diverts 80 percent of the BP’s Clean Water Act fines from their normal destination in the federal treasury to restoring damages caused to the Gulf of Mexico. But that acronym stands for Resources and Ecosystems Sustainability, Tourist Opportunities, and Revived Economies of the Gulf Coast States Act. So not all the funds go to habitat.

Still, Graham estimated that the state’s coastal agency will get $929 million for the master plan, and for the operation of its outside research arm, The Water Institute of the Gulf.

Share of general money: some of $1.6 billion

Separate BP settlement money is set aside the restoration of species that either live offshore or swim across state and federal jurisdictions. Project proposals for this $1.6 billion in spending must get approval of the five Gulf states and federal agencies.

“Some open-ocean species might depend on estuarine habitat for a phase of their lives, and that would be inside state waters,” Graham said. “So the restoration plan may decide that addressing that habitat need is part of the recovery process. And that could dovetail with one of our projects in the master plan.”

Louisiana could also get some of $700 million set aside for undiscovered problems, and to supplement projects that change as a result of monitoring.

Payment will be spread out

BP will be allowed to spread the payments over 15 years, with the first payment expected in 2017. The settlement provides some protection for the states and federal government should BP’s empire hit hard financial times. The settlement is with BP Exploration. If that subsidiary fails, BP North America would be responsible. And if that subsidiary also goes under, the British parent company would be responsible.

“The consent decree also states that if at any time a payment is missed, or the responsible subsidiary is sold, then the states and federal government can demand immediate total payment of any balance,” said Mark Davis, an attorney and executive director of the Tulane Institute on Water Resources Policy and Law.

“Of course if they all go down and there’s a bankruptcy, then you wait in line for pennies like all other creditors,” he said. “But that is highly, highly unlikely.”

Coastal funding still short

Though $8 billion is an unprecedented infusion of money for coastal restoration, it’s only a small fraction of what’s needed to finance the coastal master plan. Its advertised cost of $50 billion was in 2010 dollars. But a financial evaluation by Tulane University shows the inflation-adjusted cost will be $91 billion.

Although computer models show the plan could result in the state gaining more land than it is losing by 2060, that would happen only if the projects are completed on schedule. Meeting that deadline, the state said, calls for spending about $1.3 billion a year over 50 years in 2010 dollars.

The Tulane report concludes the state will be $70 billion short of the $91 billion target. Recurring income now amounts to just $110 million a year. In 2017, the Gulf of Mexico Energy Security Act will begin adding about $148 to $178 million per year, depending on the price of oil. And that same year, annual BP payments averaging about $500 million a year will begin for 15 years, pushing the master plan’s annual income to about $800 million.