For decades, those leading the life-and-death struggle to keep southeast Louisiana from being swallowed by the Gulf of Mexico have had a battle cry: “Put the river back into the marsh.” The thinking is that the river should be allowed to build new land, just as it had done for millennia before flooding was controlled.

But what if pollutants in the river’s fresh water will kill the marsh before those sediments can do good?

Dissenters who posed this question have been treated as outliers, if not obstructionists.

Now a pair of recently released reports gives that question new relevance.

-

A nine-year project in New England showed that fertilizer-based pollutants carried in the Mississippi River led to the collapse of salt marshes dominated by the plant species that is a signature to much of Louisiana’s southeast coast.

-

A review of research on Louisiana’s freshwater diversions by a panel of experts from outside the state concluded they could find no solid evidence the projects improved adjacent wetlands, and even saw evidence that they might hurt wetlands. The study suggested that the state’s Coastal Master Plan, built around large sediment diversions, may be forging ahead blind to the potential dangers in the river water.

The reports provide new ammunition to diversion opponents who argue for other methods of coastal restoration, as well as scientists pushing for more research before river water is released on the wetlands.

But Garret Graves, head of the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority, is having none of it. He dismissed the latest findings as too little, too late to apply to the state’s Master Plan.

With coastal Louisiana facing a death sentence of sea level rise and subsidence, Graves invoked Donald Rumsfeld, arguing the state has to fight with the science it has, not the science it would like to have.*

“Look, if we were on a sustainable posture right now, sure, maybe we could spend a few more years and spend tens or hundreds of millions of dollars trying to perfect the science, but considering where we are in Louisiana, you have to take some risks,” Graves said.

“We are going to screw up sometimes, but the consequences of doing nothing are extraordinary,” he said. “It is simply not an option for us to sit back and wait” on more studies.

Further, Graves said, the land being built at the mouth of the Atchafalaya River with water from the Mississippi shows that diversions work. “That’s a diversion that is working perfectly,” he said, “and we need to replicate it.”

New studies revive old questions

River diversions have long been the great paradox of coastal rebuilding efforts – at once its most important, yet contentious element. Primary opposition has come from fishing interests that could see their target species pushed out of interior bays to the edges of the Gulf. Instead, they support “slurry pipelines,” which use suction dredges to mine sediment from rivers and offshore locations, mix it with water and pump into the sinking basins.

That technique has been used to build as much as 400 acres of land in as little as three months. But while the pipelines are a major component of the Master Plan, coastal authority research concluded that large diversions had two critical advantages: They built land at a much cheaper cost per acre and, once set up, they could continue building land as long as the river flows.

“The land is just wasting away, like it has cancer. And now they got this plan to put more and bigger diversions? They ain’t helping us, they’re killing us.”—Lionel Serigne, operator of a Delacroix Island boat launch and live shrimp business

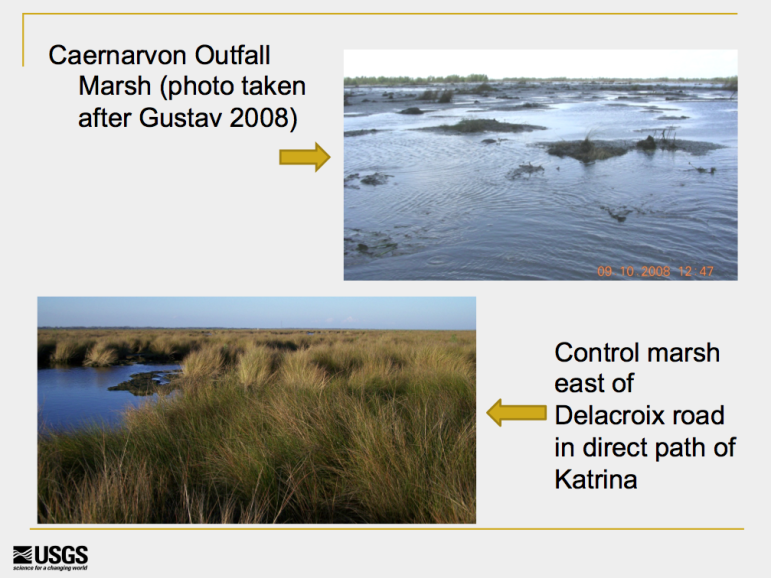

But for some diversion opponents in St. Bernard Parish, the debate over diversions isn’t just about moving their livelihoods southward. For years they’ve complained that the Caernarvon Freshwater Diversion — one of only two in the region — was actually destroying the marsh.

Opened in 1991, Caernarvon was conceived to support oyster fishers in Black Bay who were seeing their harvests decline due to rising salinity levels. It has a maximum capacity of 8,000 cubic feet per second, but its average discharge has been less than 2,000 cubic feet per second, a volume dwarfed by planned diversions that top 50,000 cubic feet per second.

But even at that small flow, fishers, trappers and others making a living off the wetlands claimed the lush blooms of freshwater plants masked a steady erosion of the soil below.

“The land is just wasting away, like it has cancer,” said Lionel Serigne, operator of a Delacroix Island boat launch and live shrimp business for more than 50 years.

“And now they got this plan to put more and bigger diversions? They ain’t helping us, they’re killing us.”

Those impressions were given scientific weight in 2008 when noted LSU coastal scientist Gene Turner published research indicating the river water pouring from Caernarvon stunted root growth of critical marsh plants and accelerated decomposition of the highly organic marsh soil. His work echoed previous studies done in other parts of the world and was followed by more research in coastal Louisiana that reached the same conclusions.

The coastal restoration establishment countered that Caernarvon was a bad analogy because it was designed to move water, not land-building sediment. Further, the state coastal authority’s research showed that the diversions would put so much sediment in the wetlands — along with the water — that they would build land and heal the ecosystem.

And they had another reaction to scientists urging caution on diversions: Southeast Louisiana was running out of time. As the coast continued to collapse, that community made no excuses for its sense of urgency.

New research: Fertilizer from the river weakens marshes

The new papers refocus scientific attention on that debate.

The New England study was led by Linda Deegan, an LSU alumna and now a senior scientist at the Marine Biological Laboratory at Woods Hole, Mass.* Her team meticulously added concentrated nitrogen and phosphorous to tides flowing into an unpolluted coastal salt marsh. The primary plant in that marsh – Spartina cordgrass – also dominates wetlands targeted for some river diversions south of New Orleans.

“When we first started this work, it was thought salt marshes would be able to sequester excess nutrients and neutralize them with little impact on the marsh itself, but that hasn’t proven to be the case.”—John Fleeger, a professor emeritus at Louisiana State University

In the first few years of the project, the nutrients ignited an explosion of growth in leaves and stems, but by the fifth year the edges of the marsh began “literally falling apart,” said team member John Fleeger, a professor emeritus at Louisiana State University. The pollutants weakened the root structure and speeded decomposition of the organic soil. The combination of stunted, weakened roots and less stable soil led to increased erosion from regular tidal currents.

“When we first started this work,” Fleeger said, “it was thought salt marshes would be able to sequester excess nutrients and neutralize them with little impact on the marsh itself, but that hasn’t proven to be the case.”

Graves said Deegan’s research did not mimic conditions found on Louisiana’s coast. Deegan’s study used nutrient loads “double to 600 percent” of those found in the Mississippi, and the tidal cycle in the New England study was more frequent and much stronger than in Louisiana, Graves said.

Fleeger agreed that there are differences between the study area and Louisiana, but he argued that the study has a bearing on Louisiana’s Master Plan because the changes caused in the New England marsh have been recorded in other research around the world.

Do diversions build land? We don’t really know

The second report, a review of published research on the impact of the state’s freshwater diversions, was requested by Graves’ agency. It looked for any conclusions that could be drawn about those diversions, including their ability to build new land, encourage plant growth and stop erosion.

The panel criticized much of the science that has become standard reference material for the state’s coastal plan as sparse, insufficient and inconclusive. One key finding: “Little evidence was available that any Freshwater Diversion in the Louisiana deltaic plan has significantly reversed the rate of marsh degradation and land loss.”

“Look, if we were on a sustainable posture right now, sure, maybe we could spend a few more years and spend tens or hundreds of millions of dollars trying to perfect the science, but considering where we are in Louisiana, you have to take some risks.”—Garret Graves, head of the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority

While the panel saw some evidence of small-scale land-building adjacent to outflows, it noted that some papers also showed that the freshwater diversions actually compromised plant growth, soil building and wetland elevation.

And, most troubling to outside researchers who have reviewed the report, the authors concluded that the Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority may be forging ahead without proper science to guide its decisions.

The authors finished by urging the agency to conduct comprehensive research to test alternative hypotheses on how wetlands respond to nutrient-rich river water.

One editor of the report, Chris Swarzenski of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Louisiana Water Science Center in Baton Rouge, said the team was surprised to discover the state and federal agencies had never undertaken in-depth research to find out how the river water would affect coastal wetlands.

“That’s actually one of the most shocking findings,” he said. “It seems everyone has just taken for granted the slogan ‘Put the river back in the marsh’ as the key to addressing the problem without ever going out in a scientific way to find out what that would do.

“It’s almost inconceivable to me that would happen, but apparently it has.”

That review panel was drawn from researchers outside Louisiana to avoid any claim of bias in a subject that has been hotly debated inside Louisiana coastal research circles for some time, Graves confirmed.

But he dismissed the report as unusable, saying the authors did not follow the state’s mandate.

“It largely didn’t answer some of the key questions the state had posed to the scientists who were putting this together,” Graves said. “Questions like informing us or guiding us on how to design, operate and maintain sediment diversions called for specifically in the Master Plan. This largely looked at the role of freshwater diversions that exist today, and again we don’t have any of those in our Master Plan.”

“It seems everyone has just taken for granted the slogan ‘Put the river back in the marsh’ as the key to addressing the problem without ever going out in a scientific way to find out what that would do.”—Chris Swarzenski, U.S. Geological Survey’s Louisiana Water Science Center

In fact, while the Master Plan 2012 lists only “Sediment Diversions,” critics point out that at least four of the nine move river water into the marsh at the rate of 5,000 cubic feet per second or less, which they contend is not large enough to move large loads of sediment deep into adjoining basins.

The panel’s chairman, John Teal of Woods Hole, replied to Graves’ critique with both fire — and compassion.

He said Graves’ charges were so inaccurate he “could not respond to them in language fit for publication.” But he relented.

“Is he right in those charges? I can respond to his claims with one word: No!” Teal said. “We did exactly what the state asked us to do in every way.”

He provided what he said was a copy of the state’s requests, which supported his point.

“They asked us to look at what had been done on freshwater diversions, and that’s what we did,” he said.

But he also understood Graves’ sense of urgency. “Look, everyone knows the only chance you have down there is to get sediment into the wetlands,” said Teal, who has been involved in Louisiana coastal research for decades.

“I agree with him that you don’t have time left, that you probably should move forward even though the science isn’t complete, mistakes and all. He’s right about that.

“But what [the report]l was saying is that while [the coastal agency] moves forward, they have to conduct research to monitor the results, so that they know what mistakes they make, and what is working.

“We found that wasn’t the case concerning freshwater diversions.”

Graves: Atchafalaya shows that diversions work

Graves insisted the state is aware of the harm that freshwater-only diversions like those at Caernarvon and Davis Pond can do the marsh plants, saying if those federal projects were built today, the state would insist that they be designed to move sediment.

Several times, he came back to one point: “Nature is showing us how to get this done” at the mouth of the Atchafalaya River and at the West Bay Diversion south of Venice.

The Atchafalaya, a distributary of the Mississippi that captures 30 percent of its flow north of Baton Rouge, began building a small delta at the end of the Wax Outlet Canal near its natural mouth after the flood of 1973. Since then it has added about 39 square miles of land thick with healthy, freshwater vegetation.

At West Bay, opened in 2004, land and healthy vegetation began to rise above the water after the 2011 flood.

“To look at the Atchafalaya Basin and to say there is not thriving vegetation there, with the exact same water that is in the Mississippi River, is a fundamentally inaccurate statement,” Graves said.

However, some scientists say the comparison is invalid because the soil on the newly built Wax Lake and West Bay deltas is different from those in the path of many of the planned diversions.

Swarzenski, who studies wetland soils, said the new deltas are comprised primarily of mineral soils, which provide a firmer foundation for plant roots and cannot be broken down by fertilizer compounds.

But the marshes along the leveed Mississippi, blocked from sediments for more than a century, now are highly organic.

“That’s sort of the whole issue,” said Swarzenski. “These organic soils are broken down by the [compounds in the fertilizer pollution] rather quickly. That’s the concern about having river water flood them.”

And that leads to a question that scientists concerned about the diversions say hasn’t been answered: How much sediment can be deposited on these sinking marshes to rebuild new land, without causing more rapid subsidence?

“These are questions some of us believe should have been answered before planning these diversions and should still be answered before we just plow ahead,” Swarzenski said.

“Yes, we know things are desperate and we only have one chance to get this done. All the more reason we make sure we’re doing it right – because if we get it wrong, we won’t have a second chance.”

*Correction: The original version of this story misidentified Donald Rumsfeld and Linda Deegan.