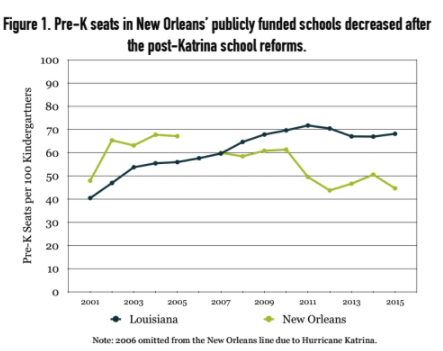

The number of pre-kindergarten seats in New Orleans has dropped substantially since Hurricane Katrina, and researchers think it’s connected to the shift to independent charter schools.

During the school year prior to Hurricane Katrina, there were 67 pre-kindergarten seats for every 100 public-school kindergarten students. Ten years later, according to the study, there were 44 seats per 100, a 34 percent drop.

Meanwhile, the number of pre-kindergarten seats for four-year-olds statewide has risen, according to the study by Tulane University’s Education Research Alliance for New Orleans.

67Pre-kindergarten seats for every 100 kindergartners before Hurricane Katrina44Pre-kindergarten seats for every 100 kindergartners in 2014-15

“The biggest takeaway for me,” said researcher Lindsay Weixler, “is the mismatch between decentralized school governance and an optional program like pre-k.”

Pre-kindergarten has positive effects on students, studies show. But it costs thousands of dollars per student, and charter schools must weigh that against the chance that those students will move to another charter school before they enter testing grades, according to researchers.

Charter schools are publicly funded but privately run. They must meet academic benchmarks, largely based on standardized test scores, in order to stay open.

In New Orleans, just 40 percent of students in a school’s pre-k stayed through third grade, when state testing begins, according to the study.

“The biggest takeaway for me is the mismatch between decentralized school governance and an optional program like pre-k.”—Lindsay Weixler, Education Research Alliance

Weixler, associate director and senior research fellow at the Education Research Alliance, conducted the research along with two others. They wrote that “insufficient incentives are in place for schools to invest their funds in pre-k in this decentralized setting of highly mobile students.”

High student mobility isn’t new in New Orleans, Weixler said. But pre-kindergarten funding usually doesn’t cover the entire cost of the program, making it a risky investment for independent charter organizations that can’t rely on a school district’s central office to help pay for it.

School system used to manage pre-kindergarten programs

Before the storm, pre-kindergarten seats in the city were managed by the Orleans Parish School Board.

Researchers spoke with employees who worked there at that time.

“They were making a very intentional decision to use their Title I funds to operate the program,” Weixler said, referring to federal funding dedicated to low-income students. “Once they lose control over the schools, they can no longer do that.”

After Katrina, the state Recovery School District took control of the city’s schools, many of which were failing. In the years since, it has turned them over to charter organizations or closed them.

Several schools overseen by the local school board became charters in the 2005-06 school year so they could repair their buildings themselves and reopen faster.

Now, all but four of New Orleans’ 86 public schools are charters.

Charter schools collect state and local funding for every student in kindergarten and above. The state provides per-pupil funding for pre-kindergarten, but only for low-income students.

The study estimates that schools spent between $3,120 and $6,920 per pre-k student — on top of the state’s subsidy of $4,580 for the 2014-15 academic year.

$4,580State funding for each low-income pre-kindergarten studentUp to $6,920More spent by schools for each pre-k student

Nearly all school leaders who talked to researchers believe in the value of pre-kindergarten, Weixler said. But some couldn’t make it work logistically or financially.

Some schools have taken on the challenge by offering tuition-based pre-kindergarten alongside state-funded seats. New Orleans College Prep launched an early learning center this year, estimating it would run a deficit until it breaks even after five years.

Other schools seek special-education students in pre-k, for which they receive more state funding.

In a decentralized district, researchers wrote, a school is likely to invest in programs that directly benefit it. If students can transfer easily, that takes away the incentive to invest.

Their research indicates that “decentralization without offsetting financial incentives can lead to reduced investments in programs that advance the broader social goals of public education.”

Charter schools weigh the costs and benefits of pre-k

Crescent City Schools offers pre-kindergarten at each of its three schools.

Akili Academy of New Orleans has 20 seats, Harriet Tubman Charter School has 50, and Paul Habans Charter School has 60.

“The funding is an issue,” said Chief Operating Officer Chris Hines. “It’s significantly less for a pre-kindergarten kid than a K-12 kid.”

Schools received $9,158 for each elementary and high school student in 2014-15, compared to $4,580 for pre-kindergarten. Funding for kindergarten students and up comes from state and local sources, while pre-kindergarten dollars come just from the state.

“We’re hoping it makes family life a little easier for our families. And we’re hoping kids are learning foundational skills in our program, both academic and social skills.”—Chris Hines, Crescent City Schools

Hines estimates Crescent City Schools spends at least $1,000 more than the state provides for each pre-kindergarten student. That includes direct costs, like teachers’ salaries and supplies, but doesn’t include operating costs like transportation or facility expenses.

“We’re able to fund it because we operate fairly large schools,” Hines said.

School leaders that offered pre-kindergarten expected future returns in enrollment and academics, according to the study. They told researchers it would help with kindergarten readiness and lead to higher test scores.

They also thought it would make the school more attractive to parents.

“We’re hoping it makes family life a little easier for our families,” Hines said. “And we’re hoping kids are learning foundational skills in our program, both academic and social skills.”

Prior research has shown school leaders respond to competition by spending more on marketing and offering services such as advanced courses, extracurriculars and child care.

Two-thirds of pre-kindergarten students remained at their school for kindergarten, researchers found. But only 40 percent stayed through third grade. That’s when students take the first standardized tests that largely determine a school’s rating.

New system has some centralized services

Hines said there’s more work in accounting for pre-kindergarten funding, too. In a traditional school district, those tasks could be handled by administrators in the central office.

“There’s more paperwork and data you’re reporting,” Hines said. “I think that might be another reason why there are fewer seats.”

The Education Research Alliance has found charter schools spend more on administration than they would have if the city’s school system had not been transformed into one dominated by charters. That’s largely due to the loss of economies of scale.

Some centralized oversight has been added during the transformation to charters.

Most schools in the city participate in a centralized enrollment lottery, called OneApp. An expulsion board was created to prevent schools from pushing students out for frivolous reasons.

Researchers think something similar may be necessary for pre-kindergarten programs.

“If policymakers want to increase school-based pre-k seats,” they wrote, “more centralized oversight might be necessary in this case as well.”