In the past several years, the BP oil spill and diversions carrying water from the Mississippi River have compromised the delicate balance of water and salt needed to sustain oysters off Louisiana’s southeastern coast, researchers have said.

Now, scientists with the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation have identified areas where the water is just salty enough for oysters to flourish.

They say their research can help oystermen shift production away from coastal areas that are depleted after decades of harvesting. And it could help the industry adapt as the state tries to rebuild its coast with massive river diversions that will pour freshwater and sediment into eroding wetlands — which could kill off more oysters.

“Oysters have always been cyclical. We’d have boom years and then lean years. … Now, there’s no recovery.”—John Tesvich, Louisiana Oyster Task Force

“The state is trying to create diversions not to optimize oysters, but to build land,” said John Lopez, director of the foundation’s coastal sustainability program. “You are going to make some areas of the coast too fresh and shift oysters elsewhere.”

Oystermen don’t want to hear it. Instead, they want salinity restored in areas they’ve cultivated for years. They say the situation is so dire, there won’t be enough oysters to sustain the industry if action isn’t taken soon.

“The salinity is so low, they can’t produce,” said Byron Encalade, president of the Louisiana Oystermen Association. “And it’s not just oysters; it’s other small animals. The food chain has been destroyed in the Lake Pontchartrain estuary.”

Oysters like water that’s not too salty, not too fresh

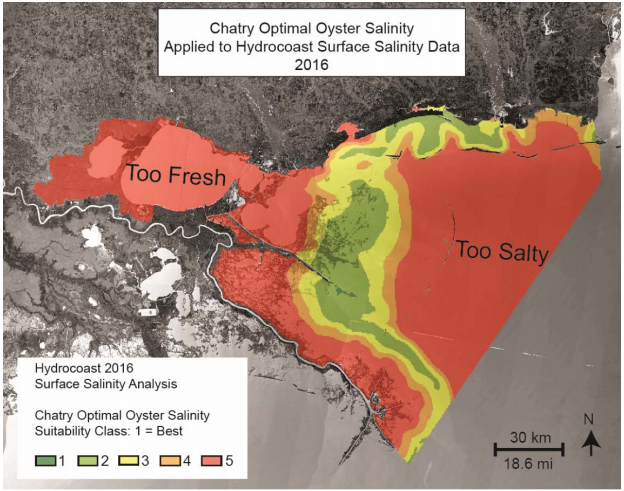

The foundation’s study, released this summer, evaluated known oyster habitats last year in the Pontchartrain Basin, which includes lakes Maurepas, Pontchartrain and Borgne as well as the disintegrating wetlands between them and the Gulf of Mexico.

The Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation has been studying water salinity and its relationship to oyster beds since 2013. The latest report builds on that research.

It evaluated the salinity of different areas and identified areas with low oxygen, known as “dead zones.”

“The state is trying to create diversions not to optimize oysters, but to build land. You are going to make some areas of the coast too fresh and shift oysters elsewhere.”—John Lopez, Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation

By mapping salinity over time and showing where oyster “hot spots” are now, scientists can determine which areas will be best suited for oyster reef restoration in years to come, Lopez said.

Coastal communities that are home to oyster families face a double whammy of global warming and subsidence. The state’s 50-year plan to save those communities — those that can be saved — relies on heavily on freshwater diversions.

Fishermen say the flood of freshwater into bays and lakes will displace some fisheries and kill off oysters.

Based on the locations of restoration projects and his research on salinity levels, Lopez said oystermen should travel away from traditional harvesting areas along the coast south of the Mississippi River Gulf Outlet.

Instead, oystermen would be better off harvesting in the Biloxi Marsh, closer to Bay St. Louis than to the Bird’s Foot Delta, he said.

The study says the eroding Biloxi Marsh would be stabilized by oyster bed development, helping it act as a “speed bump” for tropical storms that threaten the coast.

While oystermen agree that salinity levels are key to locating optimal areas to grow oysters, many disagree with the implications of the report. Among the skeptics are leaders of the Louisiana Oyster Task Force and the oystermen association, both of which represent the oystermen the research is supposed to help.

Encalade said some of the promising areas identified in the research are being harvested. But he criticized the researchers’ premise: that the freshwater making longtime oyster beds inhospitable shouldn’t be reduced.

“You gotta have saltwater marsh. Then you gotta have freshwater marsh. And you gotta have the intermedium.”—Byron Encalade, Louisiana Oystermen Association

The state’s plan to rebuild the coast calls for cutting holes in the levees along the Mississippi River south of New Orleans, which will fill bays with sediment-rich water. Proponents of these diversions say they’re the most cost-effective way to rebuild land.

Oystermen say researchers should instead focus on controlling the amount of freshwater entering those bays. Unless that’s done, they say, no amount of research will help the oystermen who rely on the Pontchartrain Basin, a diverse body of water with fresh, brackish and saltwater pockets.

“You gotta have it all,” said Encalade, who hails from Pointe à la Hache, a fishing village in Plaquemines Parish, and has harvested oysters all his life. “You gotta have saltwater marsh. Then you gotta have freshwater marsh. And you gotta have the intermedium.”

The foundation’s research also showed optimal salinity for oysters in a thin strip of water in the Breton Sound, the Chandeleur Sound, and areas along the Mississippi coast.

Most areas with optimal salinity are north of the now-closed Mississippi River Gulf-Outlet shipping channel. Fewer spots below the channel, often called the MRGO, have the right conditions to support oysters, the study showed.

“The future is north of the MRGO,” Lopez said. “We believe that’s the reality now, and that’s the reality of the future.”

Oyster beds east of the river are suffering

For the last 35 years, Louisiana has produced more oysters than any other state, according to the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation.

In fact, as recently as 2014, the oyster haul exceeded the state’s long-term average by about 2 million pounds, according to a Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries report.

But in recent years, almost all of those oysters have come from privately leased oyster grounds rather than public areas open to anyone with the right fishing license.

John Tesvich, the chair of the Louisiana Oyster Task Force, said that’s worrying because for decades oystermen have relied on a two-pronged supply — public lands and private leases.

“Hundreds of boats from coastal areas would be harvesting oysters on state ground, resulting in employment of thousands of people on public seed grounds,” he said. “They don’t have that supply anymore.”

Those who hold large private leases, where oysters are now concentrated, are doing well, he said. Smaller operators who rely on public areas aren’t.

Oyster industry says river diversions will kill even more oysters

Researchers say there are several reasons for the decay of public and private oyster beds east of the Mississippi River, including destructive mineral extraction practices, hurricanes and pollutants from the BP oil spill. Lopez also cited overharvesting.

Fishing groups also blame freshwater intrusion. They point to Mardi Gras Pass, a breach in the Mississippi River levee south of Pointe à la Hache that funnels river water into Breton Sound.

Lopez has said the pass allows sediment to be carried into the eroding wetlands, where it is dispersed naturally in areas that the state plans to rebuild using a river diversion and a marsh-creation project.

Oyster harvesters say the river water has reduced the salinity of nearby bays, decimating public seed ground. The damage to oyster beds will be more widespread, they say, if the state builds large-scale diversions.

Encalade said oystermen already harvest far from where their families had worked for decades because “there’s simply not enough oysters” left. If they’re forced to go even farther, Encalade said, harvesting will become so expensive and impractical that many will give up.

He also blamed overfishing on diversions.

“There’s overfishing because you done kill off our wildlife, so the boats descend on these little areas like locusts … You hit me in the head and bust my head, now you want to fault me for bleeding on the floor.”—Byron Encalade, Louisiana Oystermen Association

The study notes that the ideal area for oysters has shifted about eight to 10 miles to the southeast. Although researchers didn’t point to a single cause, the study says some of that movement from 2015 to 2016 “may be influenced by the opening of the Bonnet Carré Spillway and riverine flooding within the Pontchartrain Basin.”

The Bonnet Carré Spillway was partially opened in 2016 to carry water from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain in order to keep the river near New Orleans from getting too high.

“There’s overfishing because you done kill off our wildlife, so the boats descend on these little areas like locusts,” Encalade said. “Us overfishing, it’s ridiculous. You hit me in the head and bust my head, now you want to fault me for bleeding on the floor.”

The state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority has been working with the Water Institute of the Gulf to lessen the effect of diversions on fisheries. Scientists think they can optimize them by operating them at times when a relatively small volume of water carries a lot of sediment.

Tesvich and others are have long advocated that the state build land by pumping mud from the river into marshes.

And instead of directing oystermen to work farther offshore, Encalade and Tesvich want to see Mardi Gras Pass closed. That will give the industry a chance to replenish lost oyster seed.

“That’s the only thing that has changed, with the disappearance of oysters altogether in that area,” Tesvich said.

“Oysters have always been cyclical,” he said. “We’d have boom years and then lean years, and would cycle between one and the other … But that’s normal. Now, there’s no recovery.”