When we were kids, our parents took us to Florida for our summer vacation. We stayed at the Silver Beach Motel in Destin. The two-story cinderblock building had a shuffleboard court, a pool with a slide, and access to miles and miles of sugar-white sand beaches. “The Redneck Riviera,” as it was affectionately known, was a narrow strip of paradise on the Gulf Coast.

In the 1970’s, Interstate 10 was completed, making it much easier to reach “The Luckiest Fishing Village in America.” Soon, seaside motels were replaced by towering high-rises. Miniature golf, water parks, an Alvin’s Island souvenir shop and the Hog’s Breath Saloon all moved in. Our little slice of paradise had become a tourist trap.

To avoid the crowds, we moved farther down the beach, along Highway 30 A.

In the 1980’s, developer Robert Davis and architect Andrés Duany designed the planned community of Seaside, Florida. Built as an alternative to suburban sprawl and the unregulated congestion of places like Fort Walton Beach and Panama City, it became the poster child for New Urbanism. It had quaint little houses on narrow, shady streets, a defined town center with a mix of residential and commercial buildings, and plenty of green, common spaces. From the beach and the post office, to schools and restaurants, everything was within walking distance. It was an idyllic community in an idyllic setting, so much so that it was used as the backdrop for “The Truman Show,” a Jim Carrey film set in a fake, “perfect” town.

With Seaside’s success, copycat developments sprang up like sea oats along 30-A. They included Watercolor, Alys Beach, Seacrest and Rosemary Beach.

This past summer, our family revisited its old stomping grounds for the first time in many years. We rented a home in Seagrove Beach, a Seaside clone just down the road from the original. The fine quartz sand still squeaked beneath our feet, and the water along the Emerald Coast was still, well, emerald green.

We are worried that the proverbial goose that laid the golden egg has its neck on the chopping block.

After a couple of days roasting on the beach, we ventured over to Seaside. There was a long traffic jam leading into town, and we couldn’t find a place to park. Piles of bikes littered the communal lawn and day trippers from the surrounding communities packed the sidewalks and shops. Many of the quaint little houses, now second or third homes of wealthy residents from Atlanta, Houston and New Orleans, were rented out via VRBO or Airbnb. We felt like we were being trampled by Stepford wives. The idyllic planned community dreamed up by Davis and Duany had become a victim of its own success. It was Milton’s Paradise Lost.

“Maybe we can go even farther down the beach,” I suggested to my wife. “I hear Apalachicola is nice. Or we can come back in the winter – with the snowbirds from Canada.”

When I got back home, I spoke to a friend of mine, Richard Gibbs. He had been the town architect for Seaside and Rosemary Beach. “It was my job,” he said, “to protect the quality and integrity of the original plan. I was sort of like the HDLC here,” he said, referring to New Orleans’ Historic Districts Landmark Commission. “I reviewed and approved home designs and made sure people used the right materials. Some of our ideas actually came from New Orleans.”

“So, what happened to that original plan?” I asked.

“You can control a number of things with building codes and zoning restrictions,” he said, “but you can’t control why people come. Seaside quickly became a vacation destination — a lot like the Quarter today.”

“There were also conflicts between developers and residents,” he added. “One wanted to maximize profits, while the other was more concerned about quality of life. As you imagine, money often wins out in the end.”

“Yes,” I said, “I can imagine…”

New Urbanism is not really all that new. It’s actually old urbanism rediscovered. Some of the best examples can be found in the colonial cities of Latin America. From Casco Viejo in Panama City, Panama, to the old walled section of Cartagena in Colombia, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods with a defined town center have been around for centuries. Who knows, these centros históricos may have been the inspiration for Duany’s Seaside dream. Or maybe he stole the idea from our own Vieux Carré?

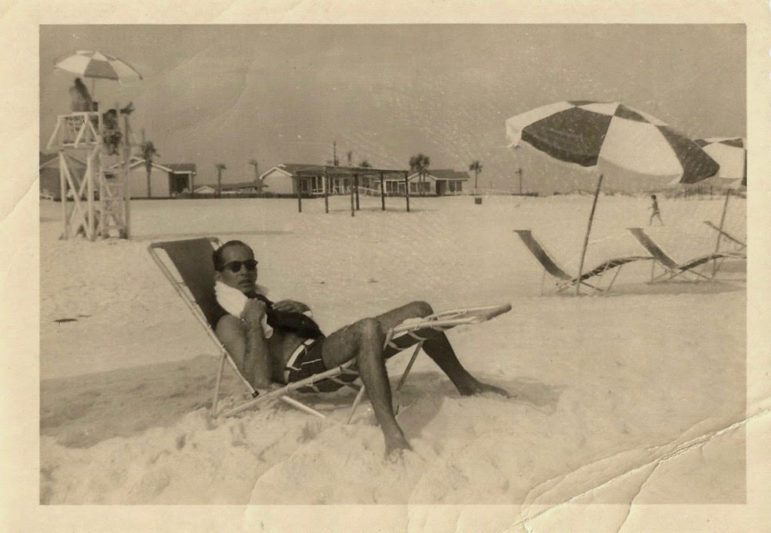

My parents met in the French Quarter in the 1950s. My mom lived with her parents on Bienville Street and my dad rented a studio apartment in the Pontalba. He ran an art school on Chartres Street and had a gallery on Royal. They made groceries at Matassa’s, shopped at Maison Blanche, met for drinks at the Napoleon House, had dinner at Marti’s, Kolb’s, or Antoine’s, and went to church on Sunday at the St. Louis Cathedral.

“Where the hell did you park?” I asked my dad the other day. “Parking in the Quarter is a &%$@ nightmare!”

“On the street,” he said. “I could always find a good spot down Pirate Alley.”

“But what about all the tourists?” I asked.

“There weren’t that many,” he said. “The Quarter was a real neighborhood back then.”

Today, that’s hardly the case. The Vieux Carré has lost much of its New Urbanist appeal. Bourbon Street is basically Disneyland for Drunks, many residential homes are now owned by absentee investors and celebrities, and cruise ships and tour buses flood the broken streets with people from the Midwest wearing Bermuda shorts and flip-flops. Supposedly there is a higher ratio of tourists to residents in the French Quarter than there is in Venice, Italy! Like Seaside, it’s a bit disconcerting. It is New Urbanism run amok — another paradise lost.

I live just downriver in the historic Bywater neighborhood. Like the Quarter and other old faubourgs, it has many of the characteristics of New Urbanism. (Andrés Duany actually built a few shoddy Seaside-like houses here after the storm.) Because of this, and because it sits on the relatively high and dry “Sliver by the River” (or the “Isle of Denial,” depending on your perspective), it has become increasingly popular post-Katrina.

Trendy restaurants, galleries and shops are popping up like cypress knees. Fancy condominiums and short-term rentals are spreading like kudzu. There is a “poshtel” (posh hostel) in the works, and there are plans for a cruise ship terminal.

Property values are increasing, but many residents, including us, are nervous. We are worried that the proverbial goose that laid the golden egg has its neck on the chopping block.

Several of our neighbors have already moved farther “down the beach.” They bought houses in Holy Cross and Arabi. Strangely, they have become urban pioneers — in the suburbs.

Folwell Dunbar is an educator and artist. He has lived in the Bywater for 18 years, but is considering moving. He can be reached (for now) at fldunbar@icloud.com

The opinion section is a community forum. Views expressed are not necessarily those of The Lens or its staff. To propose an idea for a column, contact Lens founder Karen Gadbois.