The Jefferson Parish District Attorney’s Office acknowledged Thursday that it, too, has sent fake subpoenas to reluctant witnesses to get them to talk to prosecutors. The practice will stop immediately, the office said in a written statement.

The admission comes a day after the Orleans Parish DA’s office abruptly announced it would end the practice after The Lens informed the office that it was about to publish a story reporting that legal experts said the practice is unethical, if not illegal.

Criticism of the practice in New Orleans mounted Thursday. Two City Council members said the fake subpoenas, as well as other aggressive tactics by the DA’s office, probably have eroded the public’s faith in the criminal justice system.

“No wonder people in our community don’t trust our criminal justice system,” Councilwoman Susan Guidry said at a meeting.

“No wonder people in our community don’t trust our criminal justice system.”—Councilwoman Susan Guidry

State law requires prosecutors to ask a judge to issue a subpoena if they want to interview a witness in private, typically while they’re still investigating a case.

Instead, prosecutors in Jefferson and Orleans parishes simply sent out their own notices ordering people to come in for questioning.

The Lens has found three cases in New Orleans in which witnesses got the notices. In two of them, people with ties to the defendant received them days before the trial.

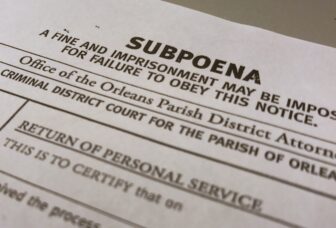

The fake subpoenas sent out by Orleans prosecutors cited state law and declared, “A FINE AND IMPRISONMENT MAY BE IMPOSED FOR FAILURE TO OBEY THIS NOTICE.”

That’s not true. The notices had no legal authority because they weren’t approved by a judge.

Have you received one of these fake subpoenas? We want to talk to you. Email editor@thelensnola.org, or call or text 504-229-2346.

Defense lawyers and legal experts said the subpoenas violated state law and rules of conduct for lawyers, which requires them to be truthful when dealing with victims and witnesses.

“There’s no question this is improper,” said Pace University law professor Bennett Gershman, a former prosecutor in New York City and an expert in prosecutorial misconduct.

The lawyer for two people who got the notices from Orleans Parish prosecutors said he thinks they may be a type of forgery.

The documents don’t include a judge’s name or signature. But Louisiana’s law on forgery includes “to alter, make, complete, execute, or authenticate any writing so that it purports … to be the act of another who did not authorize that act.”

In the course of reporting on fake subpoenas in Orleans Parish, The Lens contacted Jefferson Parish District Attorney Paul Connick’s office to find out if its prosecutors sent them out as well.

As it turned out, they had.

“Our findings revealed that ‘D.A subpoenas’ have been delivered to reluctant witnesses directly from this office and without going through the court.”—Jefferson Parish District Attorney’s Office

“Prompted by a recent press inquiry, our office initiated a review to determine whether all Jefferson Parish District Attorney’s Office personnel were acting in full compliance” with the Code of Criminal Procedure, the statement read.

“Our findings revealed that ‘D.A subpoenas’ have been delivered to reluctant witnesses directly from this office and without going through the court process.”

“The District Attorney has directed all employees to discontinue any practice that is not in compliance” with state law, it said.

The statement included two redacted examples of what the office sent out. Both are labeled “subpoena” and look like official court documents. One says the recipient is “ordered” to meet with prosecutors. The other says “requested.”

Neither threatens jail or fines like the one from Orleans Parish prosecutors.

The statement from the Jefferson Parish DA didn’t say how often the notices were used. A representative of the Orleans Parish DA told The Lens he didn’t know. Because they were sent without any notice to opposing counsel or a judge, they aren’t included in official court records.

Council members: Fake subpoenas contribute to distrust of law enforcement

The Orleans DA’s use of fake subpoenas came up at a council committee meeting Thursday, during a presentation from Court Watch NOLA on its 2016 report on Criminal District Court.

That report found a number of instances in which the District Attorney had obtained arrest warrants for victims of crimes — including rape and domestic violence — because they wouldn’t cooperate with prosecutors.

“We continue to see this where these victims, these witnesses, these defendants … are being coerced by our district attorney,” Guidry said.

Guidry, a lawyer, said she had looked at an example of a fake subpoena in a news story. “It looks for all the world like a valid subpoena,” she said.

Councilman Jason Williams agreed, noting that the New Orleans Police Department often has trouble getting witnesses to cooperate in investigations.

“The chief says he can’t close cases because people don’t want to participate with the criminal justice system. This is why,” said Williams, a defense attorney.

In defending the practice to The Lens, Orleans Parish Assistant District Attorney Chris Bowman said it’s the other way around — the office resorted to the official-looking “notices,” as he called them, because people would ignore a letter.

“Maybe in some places if you send a letter on the DA’s letterhead that says, ‘You need to come in and talk to us,’ … that is sufficient. It isn’t here,” he said. “That is why that looks as formal as it does.”

Simone Levine, Court Watch’s executive director, said she has observed the distrust of law enforcement that Williams referred to. She previously worked as the deputy police monitor for the Office of the Independent Police Monitor.

She said she frequently saw witnesses at homicide scenes refuse to talk to detectives because they didn’t trust the police.

Levine said reports like hers are meant to bring transparency to these practices, “but it’s really only transparency for one sector of the community. Another sector of the community has always known this to be the case.”

“I understand the public safety aspect of wanting, with all your being, to get a witness to come forward. But it has to be done legally.”—City Councilwoman Susan Guidry

Guidry said the DA’s office has a very difficult job, but that doesn’t justify skirting ethical rules or legal procedures.

“I understand the public safety aspect of wanting, with all your being, to get a witness to come forward. But it has to be done legally,” she said.

Cannizzaro is independently elected, not a city government employee. But his office gets part of its budget from the city. The city cut its allocation to the DA by about $600,000 this year, a source of tension between Cannizzaro and city government.

New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu declined to comment on the practice.

In an interview with WWL-TV, Cannizzarro said, “It was improper for us, it was incorrect for us to label those notices as a subpoena … I take responsibility for that.”

Local, national outcry

Tim Morris, a columnist for NOLA.com/The Times-Picayune, made a similar point as Guidry in a column published Thursday.

“Sympathizing with hard-working assistant district attorneys trying to track down witnesses and information against all sort of obstacles, it’s still crucial that the government follow its own laws and rules,” he wrote.

New Orleans Advocate columnist Stephanie Grace wrote that Cannizzaro’s office used the subpoenas to “blatantly bully witnesses in criminal cases.”

Cannizzaro also got flak from Radley Balko, an opinion writer for The Washington Post. On Twitter, he wrote, “More appalling conduct from one of the worst DAs in the country.” That type of sentiment was not uncommon on social media.

Cannizzaro’s office has not responded to requests for comment since The Lens published its story Wednesday.