Practitioners of the Vodou religion hope – pray even – for fair treatment from anyone: journalists, the anthros, ethnos, socios, religious scholars, and practitioners of other faiths.

When I saw a trailer for CNN’s “Believer with Reza Aslan” that previewed an episode on Haitian Vodou, I watched with a mixture of trepidation and hope. The host, Reza Aslan, seemed sincere and I wanted to believe that he would approach the subject with respect and honor.

Enough of the media’s exploitation and sensationalizing of Vodou as a satanic cult, when, as an initiated priestess of the religion, I know it be a beautiful religion of healing, hope and survival.

I was a little concerned that our host was a white American Muslim , rather than an actual Haitian Vodou practitioner. But then, as a white, vegan, Jewish-American practitioner myself, who am I to judge? It might be that the things of this world can only be seen clearly through the eyes of an outsider.

Vodou arose, in Saint Domingue, as Haiti was known before its successful slave revolution, through the conflicted encounter of African traditional religions, European Catholicism, Native American beliefs and masonic mysteries and magic. While a hybrid of all these different beliefs and traditions, Vodou’s African roots reach down into the oldest religious traditions on earth. It travelled on the backs of slaves brought forcibly to the New World, and it helped them endure the horrors that lay ahead. Nevertheless, Vodou to this day has some of the worst PR on earth. It is feared; it is wildly misunderstood.

Was TV about to deliver more of the same?

The Vodou episode’s sensationalized emphasis on a “battle over Haiti’s soul”did not bode well. But the host seemed capable of an open-minded, even-handed exploration of the conflict between Haiti’s two most polarized religions: Vodou and evangelical Christianity.

The show opened up with this conflict. But after spending a good bit of time on footage of massive evangelical revival meetings and intelligent commentary on the roots of the conflict, it did not flesh out the richness and beauty of the Vodou tradition in anything like equivalent detail. Some members of my Vodou society were aggravated that CNN would assume the right to debate whether Vodou is demonic, given that they would never raise such a question about Christianity or any other bona fide world religion.

No matter how long or how hard people have tried to root out Vodou, it manages to endure because it is not TV, it’s real.

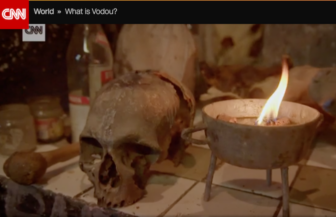

Yes, like any powerful system of belief, Vodou can be used for good or evil. But why was it that the camera focused on a skull with crossed bones on an altar with no explanation of its significance or what it was doing there? There was strangely little mention of the quite gloriously beautiful art in the rest of the Vodou temple or what any of that signified. Perhaps producers just couldn’t figure out how to pack Vodou’s rich and complex story into one episode of a prime-time TV show in search of ratings.

There were technical errors as well. For instance, why was a goat sacrificed to Ogou? Ogou, the warrior spirit, likes red rooster. Gede, the spirit who rules over death, sex and regeneration likes goat. My cynical guess is that a goat sacrifice made more dramatic footage than a chicken sacrifice. Again, ratings rule.

And why were there so few congregants at the Vodou ceremony that was filmed? Was the ceremony staged for the host and the camera crew, only pretending to be a real ceremony held by the community in service to the spirit? On the “Believer” website I came across a short video of the cameraman surrounded by women dressed in red, hamming it up for the camera. Whatever their relationship to Vodou, sure seemed like these people were more involved in stagecraft than religion.

It was also surprising to hear the oungan – the Vodou priest – refer to the spirit, Simbi, as an extremely negative force. Simbi is a serpent, but also a healer, who is notoriously shy, and a psychopomp — one who guides the soul of the departed through the afterlife.

While there are turbulent, fiery, revolutionary or magical spirits in Vodou — in addition to the gentle, benevolent ones — none are seen as evil. They are all aspects of God’s life force and all are sacred. I wondered whether this Vodou priest had been influenced by Christianity’s dualistic view that a thing is either good or evil and there is nothing in between. An essential key to health in Vodou’s world view is that power comes from balance, not from rooting out what we may judge as “negative.”

Those were my quibbles. But the show made many positive points that resonated with me:

- The lwa, the Vodou spirits, are ancestral and natural intermediaries. They speak to our humanity and help us to respect and appreciate the sacredness of our world around us.

- There is an invisible world of tremendous power and potential within the visible world. The two worlds are not in opposition but reflect and inform one another. Vodou ceremonies are a technology for reaching into the Invisible and drawing out power.

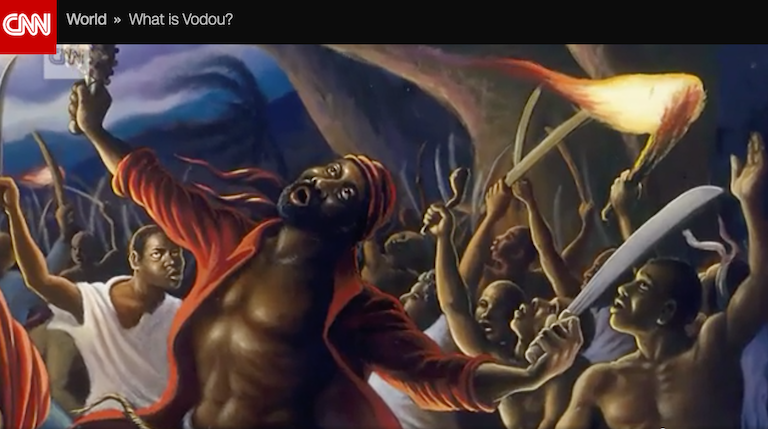

- No wonder the slaves found sustenance in Vodou and no wonder the colonists were terrified of this unseen power. It helped the slaves endure the unendurable. It kept their souls intact and their spines unbroken.

A campaign was undertaken to denigrate Vodou in order to undermine the access to power that it afforded the slaves. In our times, Christian sects and especially evangelicals continue trying to suppress Vodou and steal this source of power and pride from practitioners, an act of cultural theft.

The late Max Beauvoir, the ati or titular head of Haitian Vodou, told me that evangelical Christians were in charge of dispensing relief supplies after the 2010 earthquakes in Haiti. But in order to receive the aid, the victims of disaster had to renounce Vodou and accept Jesus Christ as their lord and savior. Convert, or go hungry and homeless.

Max also told me that evangelical preachers incited violence among Haitians by claiming the earthquakes were God’s punishment for Vodou’s supposedly demonic practices. Sound familiar? New Orleans was treated to some of that by Christian fundamentalists who argued that Hurricane Katrina was the lord’s vengeance for our godlessness.

There are no words to express the perversity of the white Midwestern preacher in the TV episode who claimed that American slaves attained their freedom the “right way” because they waited to be emancipated by their owners, while the Haitian slaves were evil because they sold their souls to the devil in order to defeat Napoleon and achieve revolution.

The Vodou faithful say, “Of course Napoleon had to lose. He didn’t realize he was fighting spirits and not men.” It is not evil to free yourself from bondage, it’s an assertion of power and a realization of selfhood. It is not Vodou that is evil, it’s the institution of slavery that is evil.

Requiring religious conversion from beneficiaries of your charity is all too reminiscent of Napoleon’s Code Noir, which mandated the conversion of slaves to Christianity. The colonists perfumed the stench of slavery by telling themselves they were saving souls. Now the stench is not of slavery but of its close kin, colonialism, that enforced conversion is meant to purge.

Aslan voices many of these same conclusions during his brief encounter with Vodou in Haiti. He seems genuinely moved by his experiences and conveys to his audience that Vodou is not evil, but is experienced as a blessing.

While some of the Vodou episode of “Believer” may be staged or otherwise faked, at its best the show encourages people to open their minds to a maligned religion. No matter how long or how hard people have tried to root out Vodou, it manages to endure because it is not TV, it’s real.

Initiated in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, in 1995, Sallie Ann Glassman is high priestess of the New Orleans based Vodou society, La Source Ancienne Ounfo. She is an artist and the owner of the Island of Salvation Botanica and founding co-chairman of The New Orleans Healing Center, at 2372 St. Claude Ave.

The opinion section is a community forum. Views expressed are not necessarily those of The Lens or its staff. To propose an idea for a column, contact Lens founder Karen Gadbois.