New Orleans – As activists march across the criminal justice landscape nationwide seeking to alter the system to its core, Louisiana has had its share of scrutiny.

Over several years, the Justice Department has intervened in both the New Orleans police department and jail. Foundations have poured cash into the city to study conditions here. Lawsuits have been filed.

And still, the disparities of wealth and race persist, leaving the jail in New Orleans filled disproportionately with poor black people.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]Only the United States and the Philippines allow cash bail.[/module]

Injustice Watch, an investigative news outlet based in Chicago, has spent the last six months focused on one aspect of this disparity: money bail.

Injustice Watch’s conclusion: Hundreds of thousands of poor, nonviolent men and women here and across the country are jailed before any proof of guilt has been offered, solely because they cannot afford to pay the bail.

Yet ending the bail-to-jail pipeline has proven devilishly difficult.

In Louisiana, New Mexico, Maryland and anywhere legislative efforts are attempted to end cash bail, the bail industry fights back.

Their lobbying machine spins up, letters are written, donations are made, swanky dinners and luxurious events are rolled out, arms are twisted.

And predictably, their efforts work.

Consider:

- In Louisiana, years-ago legislative action inserted bail into the very heart of the criminal justice system. Now bail bondsmen and the state’s elected judges work hand-in-hand to protect the system, raise campaign cash and even work for one another.

- Following the intervention of the bail industry in New Mexico, the actual language of a proposed constitutional amendment approved by voters last month was changed to essentially protect money bail.

- After lobbyists for the bail industry in Maryland spent thousands to wine and dine key legislators at a local yacht club and a steakhouse not far from the state capitol building in Annapolis, proposals to end bail stopped in their tracks. On Oct. 25, Maryland’s Attorney General tried again, and is finding tough opposition.

The pro-bail pressure comes as the nation – shaken by the consequences of mass incarceration and a fault-filled criminal justice system – is evaluating the basic fairness of a bail system that jails the poor before any proof of guilt for no other reason than the accused is indigent. Pending lawsuits on behalf of inmates around the country contend that it violates the Constitution to hold people in custody simply because they are too poor to post the bail that other suspects are able to pay.

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]In late November, two-thirds of those in Cook County jail, where Chicago is located, were being held because they had failed to post the cash bail set for them.[/module]The U.S. Justice Department even told prosecutors across the country that it opposes bail for the poor on constitutional grounds, and a bill was filed in Congress this year to end the system of cash bail.

The argument for bail reform is spurred, too, by jail overcrowding and the costs of incarcerating people awaiting trial on nonviolent charges. In late November, two-thirds of those in Cook County jail, where Chicago is located, were being held because they had failed to post the cash bail set for them.

Some jurisdictions, like New Orleans, would save millions of dollars each year by releasing the accused to await trial outside of jail.

But those efforts face significant obstacles, as Injustice Watch reported recently, and one major roadblock is the bail bond industry.

* * *

The industry’s influence is mighty – for two obvious reasons: Jobs and fear.

Cash bail is common in America. Nationally, a thriving bail industry employs upwards of 30,000 men and women who provide the grease that lubricates the criminal justice system.

Many defendants must put up a “bail bond” in which they pay a certain amount of money to be released from jail as they await trial. If they show up for trial, they get the money back.

[module align=”right” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]Many jurists and prosecutors say they believe bail is the most effective way to keep those accused of crimes from terrorizing the populace while they await processing, or to prevent them from simply fleeing.[/module]Because many people can’t tie up thousands of dollars, they go to a bail bond company. It posts the bail bond for them in exchange for a “premium,” which in New Orleans is 10 percent.

Steeped in traditions of a centuries-old system, many jurists and prosecutors say they believe bail is the most effective way to keep those accused of crimes from terrorizing the populace while they await processing, or to prevent them from simply fleeing.

Add to that mix the bail industry’s regular use of the fear-of-crime card. The result: bail remains entrenched.

Only the United States and the Philippines allow cash bail. And in most of the world, if one were to pay money to win the release of a prisoner, the act would be seen as bribery.

In New Mexico, bail is so commonly used, and the accused are so poor, that upwards of 40 percent of those who sit in pretrial custody would be free if they could come up with $500 or less.

In contrast, Washington, D.C., which all but ended money bail in the early 1990s in exchange for a robust pretrial monitoring system, releases 91 percent of defendants arrested in the District of Columbia on their promise to appear in court. And the city is not the worse for it.

* * *

Nowhere is bond industry as intertwined with the criminal justice system as it is in New Orleans, where more than 2,600 licensed agents and firms thrive in this high-crime city in a high-incarceration state.

Despite much study that shows significant racial and wealth disparities in the arrest and release of those accused in New Orleans, ending money bail to protect the poor hasn’t happened.

“One third of the people in jail are there solely because they cannot pay bail set in an amount intended to allow their release.”—Vera Institute

The court system benefits from high bail by imposing a 1.8-percent fee on each bail set. The money goes to a Judicial Expense Fund that pays for travel, attendance at conferences, coffee and bottled water for judges, and other perks.

According to an ongoing federal lawsuit, one judge said imposing those fees on indigent criminal defendants was reasonable because “the Court’s gotta eat.”

There may be another reason: The federal lawsuit, which was filed in September 2015, contended 13 judges and three criminal justice officials set high bails simply to maximize revenues.

Eight of the defendants have hired Blair L. Boutte’s political consulting firm, B-3 Consulting, to help them win their elections. (Judges, the district attorney, and the sheriff are elected positions in Louisiana.)

Boutte, who is a power in New Orleans, also has been the owner and president of Blair’s Bail Bonds for the last 20 years. His advocacy for the use of bail is well known.

Just how much money Boutte earns from his consulting business with the political and judicial elite of New Orleans is not easy to come by. Campaign filings by Louisiana candidates with the state puts the figure at more than a $1 million in recent years. Several payments were made in 2007, with most coming since 2011.

But the accounting doesn’t include many of the clients that Boutte lists on his company’s website, which range from other politicians in Louisiana to political customers in Massachusetts, Connecticut, and North Carolina, among others.

In September, the New Orleans City Council held a hearing on a bill that would have effectively ended cash bail for petty charges. A vote to move the bill out of committee for a full vote of the council failed, 2-to-2.

One of those voting against the measure was Councilwoman Nadine Ramsey, a Boutte client.

Boutte, who attended the hearing, opposes the ordinance and has said he would mount a challenge if it gets to the full council.

The bill’s sponsor, Susan G. Guidry, said she was disappointed by the vote.

“I am getting input from various parties affected by the ordinance and my intention to bring it back up with some slight amendments,” she said.

Guidry declined to discuss the involvement of Boutte in the matter.

Beyond Ramsey, Boutte’s website lists as clients 22 New Orleans judges in addition to the DA and sheriff.

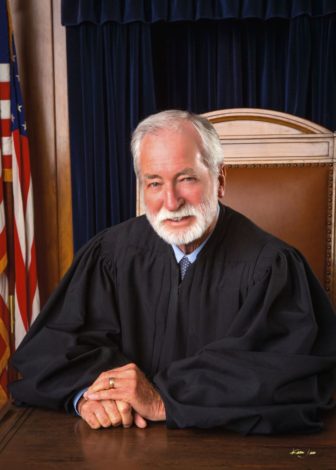

One of them is Magistrate Judge Harry E. Cantrell Jr., whose main job is to set bail in New Orleans.

Cantrell hasn’t taken a public position on cash bail. He has expressed ambivalence about an independent pretrial assessment, saying it is only one of several factors that he would consider when setting bail. He also wants to hear the recommendations of the prosecutor and defense counsel, he said in 2013 when he was first running for the magistrate’s position.

“I have never heard even a murmur of a formal proposal to eliminate money bail or even commercial surety bonding.”—Jon Wool, Vera Institute

Cantrell was known as “the stiffest bond-setter at Magistrate Court” when he was an appointed commissioner, The Advocate reported in 2013.

Ramsey, Cantrell and Boutte did not respond to emailed questions about their positions on bail or their business relationships.

What then is the impact of Louisiana’s staunch support for bail as a way to assure appearances in court?

One assessment by the Vera Institute, which has been studying the New Orleans jail and court system since 2010, looked at everyone detained before trial whose bail was less than $100,000.

How many couldn’t afford the bail?

Vera says: “One third of the people in jail are there solely because they cannot pay bail set in an amount intended to allow their release.”

Vera then studied the danger those detainees posed if they had been released awaiting trial. Using the risk assessments done by pretrial services to guide the setting of bail, Vera found that 44 percent of those detained on felony charges other than murder, rape or armed robbery on May 10, 2016 were evaluated as “low or low-moderate risk.”

Yet, New Orleans jailed them: Accused but not proven guilty.

So will any of this change?

“I have never heard even a murmur of a formal proposal to eliminate money bail or even commercial surety bonding. That’s not surprising, really,” said Jon Wool, director of the Institute’s New Orleans office. “I think Louisiana, and everywhere else, will fundamentally change its bail system, but I am not sure in what ways and what comes first and whether it happens via litigation or legislation.”

* * *

It was a unanimous decision written by New Mexico Chief Justice Charles W. Daniels that kicked off the two-year path to a new constitutional amendment.

Daniels wrote the state Supreme Court’s remarkable 2014 opinion that forced a lower court to void the $250,000 money bail that kept Walter Ernest Brown, who was accused of murder, jailed for 28 months awaiting trial.

Not once during that time were the accusations against Brown, who was 19 at his arrest in 2011, tested by the evidence. He sat jailed, presumed innocent.

Daniels and three fellow justices concluded that Brown, whose IQ is a scant 70, was not a threat to the community, had no interest in running, had petitioned twice to live at home with his parents, and would go back to his job.

Even his stay behind bars was marked by model behavior: he took well to counseling and even got his high school diploma.

Those facts about Brown, though, were ignored by the prosecutors and by the lower court judges. He was jailed simply because he couldn’t afford to pay his bail, which was set so high due to the seriousness of the charge.

And that, Daniels and his court colleagues said, violated New Mexico’s constitution.

In an ironic turn that reflects the vagaries of the all-too-often errant criminal justice system, not long after Brown was freed, prosecutors dropped the case altogether.

In an interview, Daniels put it this way: “The fundamental flaw in our system is using money to distinguish who we let out and who we don’t. It’s totally irrational.”

Matthew Coyte, an Albuquerque lawyer and president of the board of the New Mexico Criminal Defense Lawyers Association, noted that many judges seemed to ignore the 2014 state Supreme Court’s admonition that judges avoid using bail to lock up the poor.

“The fundamental flaw in our system is using money to distinguish who we let out and who we don’t. It’s totally irrational.”—New Mexico Chief Justice Charles W. Daniels

Coyte, whose outspoken advocacy for the accused earned him a Trial Lawyer of the Year award in 2013 from the Public Justice Foundation, laments how the notion of bail has become so “culturally embedded” in the judiciary.

The defense lawyers, along with the ACLU, pushed for a constitutional amendment as the path to reform.

When the amendment was first introduced in December 2015, it said simply: “A person who is not a danger and is otherwise eligible for bail shall not be detained solely because of financial inability to post a money or property bond.”

But that language brought fear to the bail industry, which relies on judges setting cash bail.

Suddenly Clayton, the American Bail Coalition policy director, was negotiating revisions to the proposed amendment. Chief Justice Daniels described what happened as the bail lobbyists “bottled up” the original bill.

New Mexico has a part-time legislature so its two-month session that ended in mid-February was busy. There were spending bills and a number of crime measures, including the bail amendment.

The speaker sent the proposed amendment to committee, where the chairwoman warned there would be no committee vote without compromise.

After two days of intense negotiations by Clayton and three state lobbyists for the industry and Daniels, new language was agreed to. Gone was the original wording.

The changes made things more complex, and more favorable to the New Mexican bail industry.

[module align=”left” width=”half” type=”pull-quote”]In New Mexico, bail is so commonly used, and the accused are so poor, that upwards of 40 percent of those who sit in pretrial custody would be free if they could come up with $500 or less.[/module]What emerged was an amendment that added a new process for evaluating affluence – a motion must be filed with the court seeking exemption from bail – and set a requirement that prosecutors must show that a defendant doesn’t require bail.

The amendment also clearly stated that judges have the power to keep violent persons off the streets – a power judges always have had.

Suddenly, the bill’s key supporters backed away, and the bail industry lined up behind the amendment.

Peter Simonson, executive director of the ACLU of New Mexico, said his group was “locked out” of the negotiations over the amendment. “For our money, it corrupted the language to a degree that we don’t feel confident that it overcomes the problems of the past,” Simonson told Injustice Watch.

So Simonson’s group dropped its backing.

Coyte and the criminal defense lawyers turned against the compromise.

Not surprisingly, the bail industry went from opposing the original amendment to supporting the one its lobbyists helped craft.

Clayton said he believes Daniels wanted the amendment so he could move New Mexico away from money bail, except in the rarest instances.

And that, he believed, would be a death knell to the bail industry.

Meanwhile, Coyte said several judges have told him the amendment will not change their behavior. “They said they would use money bonds as preventative detention in cases they believed merited it, regardless of whether the prosecutor was seeking a dangerous hearing,” he said. “As long as judges believe they are tasked with public safety they will continue to ignore the law in this area.”

* * *

Maryland is a study in contrasts.

The suburbs of Baltimore and Washington, D.C., are among the richest in the nation, teeming with the privileges of the upper class.

At the same time, two pockets of east and west Baltimore are among the nation’s poorest.

And with that poverty comes all the expected dysfunctions, crime among them.

“Jailing people who should otherwise be released because they are unable to pay bail is out of step with state and federal law and with the basic concepts of liberty and justice.”—Maryland Attorney General Brian E. Frosh

In a stunning report on the Baltimore Police Department, the Justice Department recounted the thousands upon thousands of men and women who were processed through the city’s courthouse and into the main lockup – with some 200 each month being arrested without probable cause.

The Justice Department, which found widespread lapses in recordkeeping by police, also estimated that cops may have stopped 412,000 individuals for questioning in 2014 alone.

The riots that swept the city after the death of Freddie Gray in 2015 were evidence of residents’ deep anger over their treatment by local police and criminal justice system.

For decades, the relations between police and the community might charitably be described as strained.

With some regularity over the last 15 years, the advocates of ending money bail in Maryland have tried to do away with the state’s bail system.

These advocates see bail as unfair and unconstitutional, one more way the criminal justice system treats groups inequitably.

So far, efforts to eliminate money bail have fallen flat.

Enter Maryland Attorney General Brian E. Frosh.

On October 25, Frosh asked the state’s administrative court rules committee to make changes that insure that money bail is not used to detain the poor.

His request essentially sidestepped the legislature, which has been influenced by the considerable lobbying power of the bail industry.

“Jailing people who should otherwise be released because they are unable to pay bail is out of step with state and federal law and with the basic concepts of liberty and justice,” Frosh wrote.

State Delegate Kathleen M. Dumais, who is a co-sponsor on a measure that would do what Frosh hopes to accomplish, said the reaction from bail advocates has been immediate and decidedly negative.

She and her colleagues have gotten hundreds of calls since Frosh’s letter was made public in late October. “I received 20 calls today,” Dumais said on November 17.

It’s little wonder.

Once a year for several years, the Maryland Bail Bond Association has spent thousands of dollars to take the entire judiciary committee of the House of Delegates to swanky meals at Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse or the Annapolis Yacht Club.

This year the event cost the association $3,256, the cheapest outlay for the annual event since 2012.

The organizing lobbyist Michael Canning did not respond to emailed questions about the events.

Clayton of the American Bail Coalition, fresh from his work in New Mexico, is now ready to do combat in Maryland.

“We are fighting the Maryland Attorney General’s effort, which is based in part on a letter he received from Eric Holder,” Clayton said.

In March, before he left the Department of Justice, Holder wrote to officials in 50 states urging them to protect the indigent.

“Courts must not employ bail or bond practices that cause indigent defendants to remain incarcerated solely because they cannot afford to pay for their release,” Holder wrote.

Delegate Dumais doesn’t think change will be quick.

Dumais promised to introduce legislation in 2017 to “strengthen, not outlaw” bail.

Just how different any measure might be, however, is at the heart of any debate in Maryland’s future. And it’s likely to be intense.

* * *

As the struggle over fixing bail confronts local officials across the nation, federal action too is possible.

Already, U.S. Rep Ted Lieu, a Democrat whose district encompasses Los Angeles, has introduced what he calls the No Money Bail Act of 2016.

The measure was referred to committee and no action has been taken.

But just introducing the bill was enough to produce hysterics from the bail industry.

“The bail industry is under attack!” the Professional Bail Agents of the United States said in a statement.

“The introduction of [the bill] should serve as a wake-up call for the commercial bail industry,” the group continued. “Our opponents are boldly and unapologetically calling for the elimination of our industry.”

Jim Asher is the Washington Editor for Injustice Watch, an investigative nonprofit news organization based in Chicago. Read more of Injustice Watch’s coverage about bail at http://www.injusticewatch.org.