State law says the public is entitled to observe how government bodies make decisions. But board members of Lusher Charter School privately discussed how to respond to a teachers’ union drive, using a boardwide email group. And they set up several private meetings that appear to have circumvented the Open Meetings Law.

Teachers at Lusher Charter School were gathering signatures to form a union, an effort that pitted colleagues, parents and board members against one another.

In early April, organizers asked the school’s board of directors to recognize the union at its next meeting — the first step toward negotiating a contract.

Board president Blaine LeCesne acted quickly. He organized two meetings with board members and union organizers.

Meetings like this must be open to the public if a quorum, or majority, of the board or one of its committees attend. The Louisiana Attorney General’s Office has advised that the public should be notified of a meeting if all board members are invited.

LeCesne had another idea. “If at any point we reach quorum level, one or two of us may have to step outside,” he wrote in an email to the rest of the board.

That’s the definition of a “walking quorum,” and it’s illegal.

It’s one of several instances in which Lusher board members appear to have violated the state law that requires public bodies to conduct business in the open.

The evidence is in black and white — thousands of pages of emails among board members over about five weeks. The emails, released to The Lens in response to public records requests, show extensive, boardwide discussion of public policy, all held in private:

- How should the board respond to the union drive?

- How should they phrase a key resolution?

- Who on the board supported the union, and who was against it?

At times, Lusher board members indicated that they knew they shouldn’t discuss these matters over email as a group. Time and again, however, they went ahead and had discussions that, according to the Open Meetings Law, should have taken place in public.

Lusher union drive investigationEmails reveal board’s struggle to guide Lusher Charter during spring union driveRead the emails

There is already “a lot of bitterness, distrust, suspicion, accusations on the Lusher campus,” wrote board member Chunlin Leonhard to the rest of the board before it met to consider the union’s request. “Our failure to face the issue, have an open and honest debate, and provide guidance on this issue will make us look weak as a board and damage our legitimacy.”

Like this one, many of the discussions occurred on an email group called “Lusher Board Only.” Its existence, and the frequent discussions that have taken place there, raise questions about whether Lusher board members have systematically violated the Louisiana Open Meetings Law.

There’s nothing wrong with board members passing along information by email, said Adam Marshall, an attorney with the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press, a Washington, D.C., organization that advocates for freedom of information.

But if they use email to discuss matters, “and then only the outcome of that deliberation is presented publicly, I think that violates the spirit of the law, if not the letter of the law.”

The emails show that what board members said about the union in public was just a portion of their discussion.

At a public meeting on April 23, they engaged in a spirited debate about whether a union would strengthen or damage the heart of the school. They voted 6-5 not to recognize the union.

Five days later, the board convened to pass a resolution promising to remain neutral in the upcoming union election. This time, the conversation lasted as long as a TV commercial break. All six board members there voted for the resolution.

“You’re supposed to see the deliberations. It’s not the Open Decisions Act. … It’s the Open Meetings Law.”—Adam Marshall, open-government expert

When The Lens asked how they had come to an agreement, three board members said they had heard one another out at the earlier meeting.

Board Secretary Rachel Wisdom said they had run the resolution by their lawyer, but “we haven’t been deliberating behind the scenes. Nobody expressed their views about whether they were going to agree like in an email chain or anything like that.”

Their emails show otherwise.

In the days before the April 28 meeting, board members emailed versions of the resolution back and forth among the group and discussed whether they’d support it. The final version included a new paragraph saying administrators could share views that could help teachers make a “sound and fully informed decision.”

Wisdom stood by her characterization that the board didn’t deliberate outside a public meeting.

“To me, deliberation is when you’re going to vote on something,” she said. “It’s when something is proposed for a vote. And we voted at the meeting.”

Wisdom said she doesn’t believe “it’s the intent of the Open Meetings Law to have a public body draft a resolution at a meeting. But maybe I’m wrong; I’m just not really an open meeting expert.”

But the drafting of the resolution isn’t the issue; it’s the discussion and revision.

“You’re supposed to see the deliberations,” said Marshall, the open-meetings expert. “It’s not the Open Decisions Act. … It’s the Open Meetings Law.”

“To me, deliberation is when you’re going to vote on something … And we voted at the meeting.”—Lusher board Secretary Rachel Wisdom

That law states that public business must “be performed in an open and public manner” and that citizens should be aware of “the deliberations and decisions that go into the making of public policy.” It requires public bodies to notify the public that they are planning to meet, to publish agendas describing what they’ll deal with, and to keep a record of what they discuss and decide.

The law applies to governmental boards and commissions that set public policy and spend taxpayer dollars, such as city councils and school boards, including charter school boards.

There are some exceptions. Public bodies can close a portion of a meeting for what’s called an executive session. There they can privately discuss strategy for a lawsuit or collective bargaining, for instance.

But those private meetings between the board and the pro-union teachers weren’t negotiating sessions. LeCesne told board members that he planned to have “a higher level policy conversation” about what the teachers wanted.

“The effort to make sure we complied with [the law] is now being misconstrued and misinterpreted.”—Lusher board President Blaine LeCesne

He told The Lens he was trying to follow the law, not avoid it. He would have canceled a meeting, he said, if a quorum of board members had shown up.

“These are good people on the board who have the best interest of the school at heart. They are doing this without compensation,” he said. “The effort to make sure we complied with [the law] is now being misconstrued and misinterpreted.”

Despite his efforts, the April 12 meeting between board members and union organizers appears to have violated the public meetings law anyway. A quorum of the board’s Executive Committee was there. That means the public should have been notified beforehand and it should have been held in the open.

Here are three ways that the Lusher board shut the public out of their discussions regarding the teachers’ union.

Board met privately with union organizers, opponents

The board held four private meetings: with union supporters on April 12 and 13, and with opponents on April 18 and 20.

Individual members of a public body can discuss business without notifying the public and holding an official meeting — as long as a majority of the body or a committee isn’t there and they’re not trying to circumvent the law.

“If at any point we reach quorum level, one or two of us may have to step outside.”—Blaine LeCesne, in an email to board members

However, the Louisiana Attorney General’s Office has recommended that public bodies notify the public of a meeting if all members are invited, as they were in these cases.

If a quorum of a public body were to show up, the Attorney General’s Office has said, it would have to be conducted according to the Open Meetings Law.

“At no time during any of these meetings was anything close to a quorum ever realized,” LeCesne said.

Actually, five members of the full board — one shy of a quorum — were there.

Three of them are on the five-member Executive Committee, which is empowered to take action on behalf of the full board.

Four board members, less than a quorum, attended the second meeting on April 13; a fifth participated by phone, according to sources who were there and asked to remain unnamed.

The Attorney General’s Office has advised that a public body could run afoul of the Open Meetings Law if a public official acts “in a manner specifically intended to avoid an actual quorum, and the effect of his or her actions provide an identical result to what would occur if an actual quorum did discuss the issue.”

The Orleans Parish School Board issued the charter for Lusher. Its agreement requires the school to follow the Open Meetings Law. Through a spokesman, superintendent Henderson Lewis Jr. declined an interview.

James Brown, the primary attorney for Lusher, said due to attorney-client privilege he couldn’t comment on whether he had advised the board on open meetings.

“Perhaps we could, again, have two meetings – so as not to have a quorum present?”—Board member Kiki Huston, in an email to board members

After other faculty members learned of the board’s meetings with pro-union staffers, a teacher requested that opponents get a chance to make their case.

Board member Kiki Huston emailed the group, “Perhaps we could, again, have two meetings – so as not to have a quorum present?”

Huston told The Lens by email that they held the small meetings because “we did not want to violate open meetings laws.”

She said the “purpose for those meetings was to listen, not ever discuss board business.” That’s not a distinction in the Open Meetings Law. It applies when a public body meets to “receive information” about something under its power.

5Board members attended the first meeting with union organizers6Would have been a quorum of the full board, requiring an open meeting

At a public board meeting on April 16, some people in the audience asked when the board would hear their concerns. Huston said the board had met with teachers twice.

“It’s not for everybody to come speak,” Huston said, according to Uptown Messenger. She didn’t mention the two meetings to be held in the coming days.

Chris Reade, the father of a rising fourth-grader at Lusher, said board members told parents that they would meet with them, but they didn’t. If the teacher meetings had been open to the public, he or his wife probably would have attended one of them.

These meetings apparently influenced board members. After meeting with union opponents, Wisdom and Huston argued that the board should delay the upcoming vote.

“The ONLY thing the non-union side is asking for, is for us to slow down the process,” Huston wrote.

That, too, became a topic of private debate, with LeCesne contending that delaying a decision would amount to a rejection of the union.

Emails show debate about whether board should ignore union petition

Board members were faced with a decision. Would they vote on the union’s request for recognition? Or would they just ignore it?

Failing to address the request would have the same effect as voting against it. And if they delayed, advised attorney Mag Bickford, the union could simply ask a federal agency to call an election.

The board was set to consider the union’s request on April 23. As the date approached, board members engaged in a heated debate by email about delaying the vote. Those discussions signaled their position on the union, which could be a problem under the Open Meetings Law.

11People were on the Lusher board at the time9Sent emails discussing how they should respond to the union’s petition

Board Vice President Paul Barron said they should stay out of it and let the teachers decide in a schoolwide election — an approach favored by union opponents. “Since I prefer an election, I would like to avoid a rancorous discussion, particularly because it will result in comments that will be unfair to the administration,” he wrote to the entire board.

Richard Cortizas, a board member and the former lead attorney for the city of New Orleans, agreed. “Frankly,” he wrote, “one could reasonably argue that our responsibility as a board is not to accept a petition based on the information or lack thereof received.”

Barron declined to comment for this story; Cortizas and Bickford didn’t respond.

“Contentious public meetings come with the territory of being on a public Board. … Indeed, the rancor will increase exponentially when we are perceived as running from our responsibilities.”—Blaine LeCesne, in an email to board members

Others said the board should hold the meeting as planned.

Besides, LeCesne argued, “Contentious public meetings come with the territory of being on a public Board. … Indeed, the rancor will increase exponentially when we are perceived as running from our responsibilities.”

Wisdom pressed the issue. “By my count, there are 5 board members who want to call [off] this meeting so as to have more time to get information and assess it, and to allow our community to do so too. I ask that our requests be heeded.”

The Open Meetings Law doesn’t address the use of email among members of a public body, but the Attorney General’s Office has advised that it’s inappropriate to use email to circumvent the purpose of the law to find out how others would vote on something.

The office said a judge would probably consider whether the communication “encourages further discussion or whether it merely seems to be passing along information, as well as the number of individuals from a public body involved in the email chain.”

All 11 board members received these emails, and at least nine participated in the discussion.

“The ONLY thing the non-union side is asking for, is for us to slow down the process.”—Kiki Huston, in an email to board members

“If these deliberations and communications are taking place in secret, then that participatory aspect of our democracy is being undermined,” said Marshall, the open-meetings expert. “And that’s a huge problem.”

LeCesne told the group it would be easy enough to deal with their concerns: Just vote at the meeting to table it.

“But that vote has to be made in an open meeting,” he wrote, “and will trigger the same substantive discussion on the UTL [United Teachers of Lusher] petition that some are seeking to avoid by not meeting.”

Their emails left little doubt about how most board members would vote when they met in public.

The five members who said by email that they wanted to hold the meeting voted to recognize the union. Of the six people who voted against the union, at least four of them had argued to postpone a decision or not vote at all.

Board discussed key resolution out of public view

Five days after the board voted against the union, they met again. One of the board members walked in with a resolution pledging that the board would remain neutral.

Wisdom read it aloud. It stated that the administration could share “information and views” to inform the teachers’ decision, but there was to be no intimidation. (Federal law already prohibits such intimidation.)

“We haven’t been deliberating behind the scenes. Nobody expressed their views about whether they were going to agree like in an email chain or anything like that.”—Rachel Wisdom

Wisdom told the audience that the board was not “gagging” the administration. “We want a fair process,” she said. “I think everybody here agrees with that. I just wanted the people sitting out there to understand our intention, as I understand it.”

After brief comments from LeCesne and Leonhard, the six members there unanimously approved the resolution.

That agreement was reached over the course of an email conversation in which board members shared drafts with the entire board and administrators.

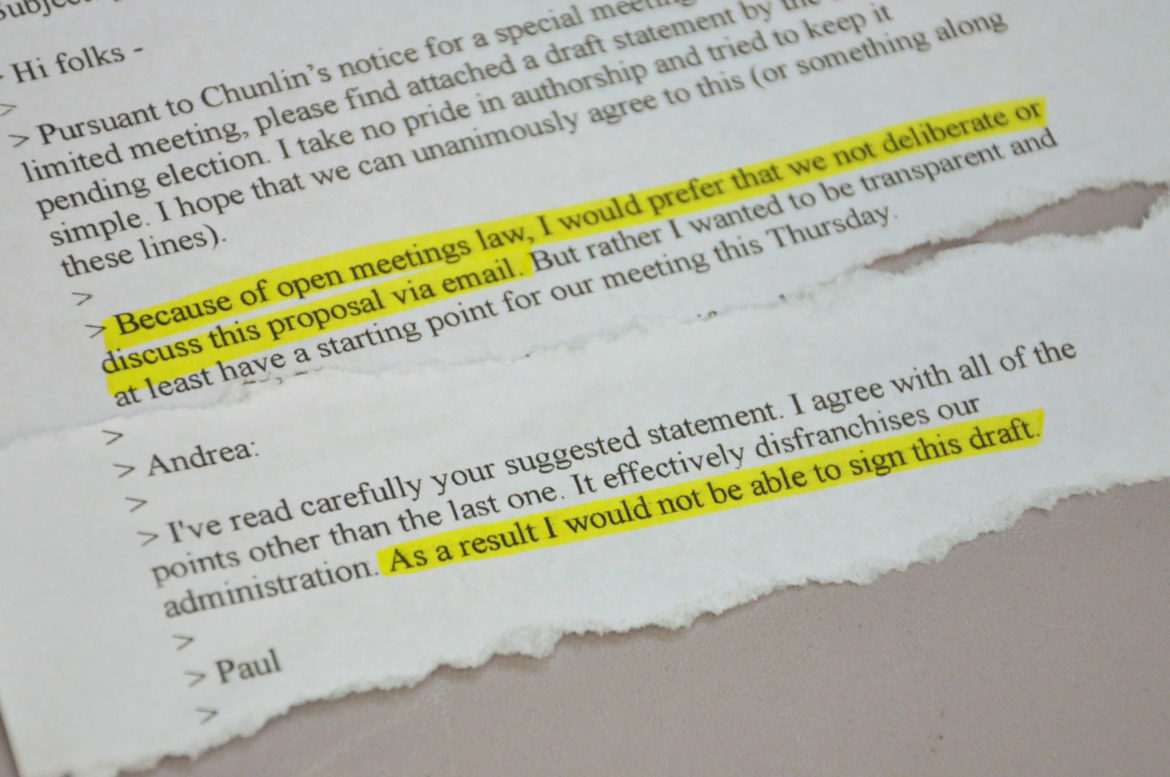

Three days before the meeting, board member Andrea Armstrong drafted a statement from the board and sent it to an email group called “Lusher Board and Administrators.” “Because of open meetings law, I would prefer that we not deliberate or discuss this proposal via email,” she wrote.

Nevertheless, Barron responded that he wouldn’t sign it because one part “effectively disenfranchises our administration.”

Board member Reuben Teague asked why and volunteered that he would sign it.

Then Leonhard sent the board and administrators a draft, noting that she, too, wanted to delay any discussion until the public meeting in order to comply with the law.

If a series of conversations “effectively stifles any further discussion of the issue at a public meeting by the public body, this could raise concerns under the Open Meetings Law.”—Louisiana Attorney General’s Office

However, Wisdom sent an email to the group offering an amendment. Leonhard responded to say she accepted it, adding, “Please note that I did not copy anyone else on this email because I don’t want to engage in a discussion of this by email.”

Wisdom forwarded Leonhard’s acceptance to three other members: Alysia Loshbaugh, Cortizas and Barron. “I still need Richard to object to protect us,” Wisdom wrote, “but this is a very good sign.”

Cortizas did exactly that, sending an email to the board and administrators group saying the resolution was unnecessary because it merely affirmed the board’s vote and what the law requires.

About 15 minutes later, Wisdom emailed Leonhard, the board and administrators, stating she had “an idea how to address Richard’s objections and suggestion.”

The next day, Wisdom suggested another change: She wanted to make it clear that the administrators could express opinions about the union. That language isn’t in Leonhard’s draft, but it’s in the final resolution.

None of this discussion occurred in public. Barron wasn’t even at the meeting where the resolution was approved.

3 of 11Board members offered drafts of the resolution3 moreOffered input

One day later, the Lusher administration sent an email to teachers warning them the union would hamper communication and create an adversarial atmosphere.

“If they’re drafting this whole thing [the resolution] online,” said Marshall, the open-meetings expert, “without the ability of the public to see this happen or to provide comments, then it’s all just kind of taking place behind the curtain.”

Regular visitors to the New Orleans City Council occasionally see council members object to something in an ordinance and offer an amendment. Told that, Wisdom responded, “I don’t know if that’s correct. I don’t go to City Council meetings. Other than this, I’ve never done anything that’s remotely governmental.”

The board’s actions appear to violate the Open Meetings Law in a couple different ways.

The law prohibits the use of “electronic communication to engage in any secret balloting” to learn how members would vote, according to the state Attorney General’s Office.

It also has warned against forwarding emails to members of the board, like Wisdom did.

Individuals or groups of less than a quorum can email about public business, the agency said in a 2012 letter regarding the Mandeville City Council. But there could be a problem if those emails are forwarded to others, “which could result in an e-mail chain reflecting a quorum of council members’ opinions on a matter which will ultimately come before a vote.”

“If they’re drafting this whole thing online … then it’s all just kind of taking place behind the curtain.”—Adam Marshall, open-government expert

Such exchanges could amount to an electronic version of an illegal “walking quorum.” That refers to a practice in which members of a public body rotate through a meeting room so they all have input, but a quorum isn’t present at any time.

If a series of conversations “effectively stifles any further discussion of the issue at a public meeting by the public body, this could raise concerns under the Open Meetings Law,” the agency advised.

All 11 board members received the messages and drafts. Besides the three board members who wrote drafts, at least three board members offered input.

Three spoke at the public meeting.

Caroline Roemer Shirley, the head of the Louisiana Association of Public Charter Schools, said she couldn’t comment on whether the Lusher board broke the law.

“I don’t think it’s OK for governing bodies to intentionally try to avoid public conversations,” she said. “Charters are to follow public meeting law, and when in doubt should ask if it is how they would want other public bodies to conduct business.”

Robert Scott, president of the Public Affairs Research Council of Louisiana, said boards like Lusher’s need to think about how their actions appear.

“You want to make sure you’re conveying the appearance that you’re a transparent board,” he said. “That’s important to build confidence and trust to the public that you’re serving.”