The story told about religion these days is one of fear and fighting. This election cycle is filled with talk about deportations and bombing campaigns. Presidential candidates are even casting suspicion on religious communities as anodyne as the Seventh Day Adventists. W.E.B. Dubois said, “The problem of the 20th century is the problem of the color line.” The problem of the 21st century may be the problem of faith lines.

How can people of different faiths — and of no faith — come together to resist conflict and violence and instead create understanding and peace? One hopeful harbinger is the interfaith movement, a very recent phenomenon. Throughout recorded history, there have been religiously tolerant civilizations encompassing disparate peoples and beliefs. The modern interfaith movement, however, marks the first time that the world religions themselves have actively sought to understand each other and work together, to varying degrees.

That was the spirit animating a community potluck dinner I recently attended at the New Orleans Healing Center on St. Claude Avenue in the Marigny neighborhood. The dinner exemplified a kind of positive counter-narrative, with people sharing food and bonhomie along with their religious views and stories. It was open to all, and no invitation list could have rivaled what walked through the door that evening.

The guests were an “only in New Orleans” slice of the world, including a Vodou priestess, Southern Baptist seminarians, self-described “nons” (ranging from atheists and agnostics to people who embrace spirituality but reject organized religion), a Comanche shaman, visitors from Israel, Garden District ladies, Bywater hipsters, a Spiritual Church bishop, a young man from Connecticut who had just bicycled across Asia and a score of assorted others.

… media tend to sensationalize violence as religious when there are complex social and economic drivers behind it as well.

The tone of the conversation was indeed tolerant and peaceful but went far deeper than “I’m okay, you’re okay” affirmations. We listened to difficult personal stories, about families unable to accept religious conversions and annual set-tos at holiday time. But we also heard an encouraging account of how a conservative Christian family was able to embrace their son’s non-religious partner on the basis of powerful shared experiences, despite divergent beliefs. The Comanche shaman echoed that anecdote, saying that experience is just as important as belief. She emphasized the importance of finding and sharing our stories.

One of the Baptist seminarians spoke movingly of tolerance as the innate nature of religion. As a Bible-believing Christian, he could not affirm other theologies as paths to salvation, but he felt compelled to put love first. Sallie Ann Glassman, Vodou priestess and co-founder of the Healing Center, talked about her birth family, which included not only atheists but also Kabbalists (Jewish mystics). She remarked that religion is a natural calling for her since she understands everything to be sacred.

Dinner conversation eventually turned from the personal to the political. A young Israeli held the media accountable for fomenting religious violence. The bicyclist concurred, saying that in the course of his travels he learned how much of what he had heard or read was wrong. The dinner guests generally agreed that the story the media tells about religion is overwhelmingly one of conflict: Islam and terrorism, of course. Buddhists versus Hindus (maybe the 25-year Sri Lankan civil war did not make headlines here, but it did elsewhere). Christian extremism, the more extreme the better. The Westboro Baptist Church, comprised of a few dozen members, gets more ink for trampling the American flag and picketing soldiers’ funerals than the other 33 million Baptists in this country who operate charities, hospitals, universities and the like.

Moreover, media tend to sensationalize violence as religious when there are complex social and economic drivers behind it as well. Our political rhetoric around faith grows increasingly ugly, and we are being embroiled in religion-implicated warfare in more and more locales.

The conflicts are real, of course. As noted by Pres Kabacoff, co-founder of the Center with Glassman, we live in a broken world. The media narrative, however, emphasizes conflict while neglecting the myriad social goods that people of faith deliver every day and everywhere to help mend that broken world.

Interfaith venues can be as distant as the Vatican in Rome or Al-Azhar University in Cairo, where clergy and scholars meet for formal dialogue, or as close as the streets of New Orleans. After Hurricane Katrina, faith communities did much of the frontline response work here while the government sector floundered, and a significant part of that work was done on an interfaith basis. Churches partnered with Buddhist temples to deliver emergency health care. Mosques and synagogues collaborated to house evacuees and get kids back in school. The list goes on, and the interfaith action here continues to go forward around our most critical and difficult community issues.

The Isaiah Institute of New Orleans grew directly from the faith-based response to the storm. Beginning with African-American pastors and churches in Central City and the Lower 9, it now includes over 60 congregations of different faiths across the metropolitan area. Joe Givens, executive director of Isaiah, led the charge for the NOLA Interfaith Peace Initiative, a visionary plan to coalesce a wide range of religious communities in resisting and resolving street violence. Each of the scores of signed-on congregations would adopt the streets around it and work intensively with neighborhood youth.

Funding for the initiative was derailed by political machinations, but, happily, Isaiah’s initiative was not defeated. Instead it has been creatively transformed. Icons for Peace, a young people’s coalition sponsored by Isaiah, is now using its youth-culture expertise to organize street peacemaking via basketball, social media campaigns, spoken word and rap.

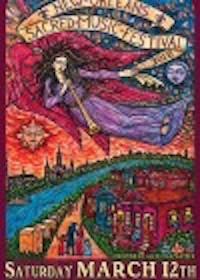

The dinner concluded with an invitation to those present and to everyone across the city to attend the day-long New Orleans Sacred Music Festival on Saturday, March 12. The festival celebrates the music and art of the world’s religions and cultures, especially as represented in our local community, but also including Tibetan monks creating a sand mandala, a Hindu fire sacrifice, Moroccan Malhoun music, a Vodou ceremony and lots more. For the first time in its five-year run, the fest is free of charge, thanks to the Jazz & Heritage Foundation and other sponsors. It will kick off at 10 a.m. with a silent walk from St. Roch Cemetery to the Healing Center led by the Icons for Peace.

Erik Schwarz is managing partner of Interfaith Works, a nonprofit based in New Orleans which is supporting the festival. Schwarz is also co-director of Civic Mix in Washington, D.C. Previously he worked at the InterFaith Conference, the National Cathedral and Episcopal Church House in Washington. In his deep past, Erik ran an art-services company in New York City and worked offshore in the Gulf.