The U.S. Supreme Court ruled Monday 6-3 in Montgomery v. Louisiana that prisoners serving mandatory life sentences without parole for murders they committed as juveniles should have a chance at release via a resentencing hearing.

Attorneys who specialize in juvenile justice called the decision “potentially sweeping” but warned that resentencing hearings were far from a sure path to freedom.

Read about Henry Montgomery’s crime, his trial and the debate over mandatory life sentences for juveniles in our story, published in partnership with the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange.

Though parole boards will now have to review the sentences, they won’t have to give parole, said retired law professor Victor Streib, an internationally renowned expert on the juvenile death penalty and juvenile justice. “And it would be very typical for them not to.”

The ruling means that the 2012 Miller v. Alabama decision — which said that mandatory life without parole sentences for juveniles are unconstitutional on Eighth Amendment grounds — should apply retroactively. Hundreds of prisoners across the country would qualify for a resentencing hearing.

Until today’s ruling, the landmark Miller decision was the latest in a series from the court rooted in the idea that children should be treated differently than adults because they are less culpable for their actions and have the potential to change.

“It’s a step in the same direction we’ve been going,” Streib said. “It follows the same argument that kids are less culpable and aren’t as deserving of punishment as adults — so in a way, this decision would be expected. The only thing that’s unusual is that the court would say that a ruling is not just effective from now on, but that it should apply to all the older sentences.”

”Symbolically, the ruling is interesting … But in fact, whether or not any of these child offenders are paroled is still up to the parole board.”—Victor Streib, expert on the juvenile death penalty

Another attorney who has represented inmates sentenced to death before the U.S. Supreme Court called Monday’s decision “potentially sweeping.”

However, John Mills of Phillips Black, a nonprofit public interest law firm, cautioned that judges can still hand down life without parole at their own discretion.

“That is happening to people in jurisdictions where they’ve received retroactive relief under state law,” Mills said from his San Francisco office. “Their prize for having won that victory is a new, discretionary sentence of life without parole. And that kind of sentence will be available unless and until the U.S. Supreme Court holds that life without parole itself is unconstitutional.”

Mills was one of the authors of a 2015 report that documented the racial and geographical disparities in juveniles sentenced to life, finding that a quarter of life-without-parole terms were handed down in just seven urban counties in the country — including Orleans, Jefferson and East Baton Rouge parishes.

Daniel Macallair, executive director of Center of Juvenile and Criminal Justice, called the decision a humane one. It brings the United States more in line with the rest of the world, he said. The U.S. is the only country in the world that allows juveniles to be sentenced to life without parole.

“It’s the right thing to do,” he said. “The rest of the world has recognized the idea that it’s not a good idea to sentence children to die in prison without any hope of release.”

“It’s great news,” said Henry Montgomery’s cousin Dianne Coleman. She predicted she and her cousin would have a joyful conversation on Sunday, when she makes her regular visit to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

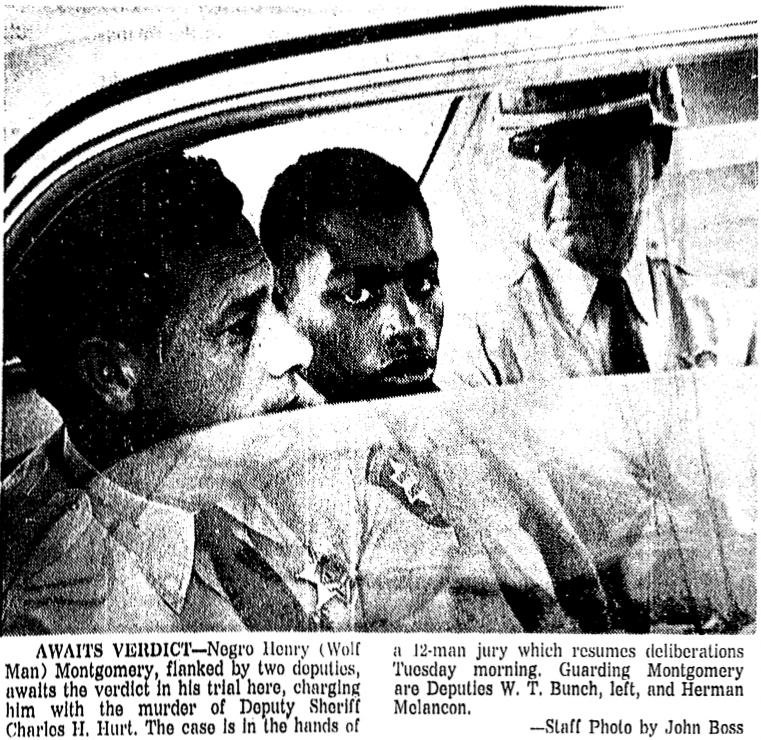

Montgomery has spent decades in prison since he was convicted in the shooting death of sheriff’s deputy Charles Hurt in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1963. He was 17 at the time of the murder.

People with ties to Angola said that they were sure that Montgomery had already heard the news. Norris Henderson, head of the group Citizens for Second Chances, which works on behalf of affected inmates in Louisiana, said that word had spread “like wildfire” to Louisiana’s 300-plus inmates serving life-without-parole sentences for crimes committed when they were under 18.

“By now, everyone in corrections in Louisiana knows,” said Henderson at midday Monday, several hours after the decision was released.

Henderson and other people on the ground in Louisiana spent Monday determining next steps, to see whether the state could establish a blanket parole eligibility for all affected inmates, for instance, to avoid individual re-sentencing hearings in each case. Despite the court victory, many questioned were left unanswered, said Mark Plaisance, one of Montgomery’s lawyers. His hunch was that the case would head back to the district trial court to deal with Montgomery’s previously rejected re-sentencing petition. Last year, the Louisiana Legislature allowed those in Montgomery’s situation to be re-sentenced for life with possibility of parole after serving 35 years, so that was a likely outcome, Plaisance said.

Because of the sheer number of juvenile-life cases in Louisiana, Plaisance predicted that the state’s district courts were about to be “bombarded with petitions.” Each court will have to decide the very basics: how the cases should be prioritized, whether the petitions will be fought and how hard, Plaisance said, noting that the Louisiana Public Defender Board’s budget was already tight.

“Given the board’s financial straits, they are certainly not in a place to fund re-sentencing hearings on 300-plus defendants,” he said. “But it’s got to get done. We have to determine how to do it fairly and adhere to the Constitution, now that we have a ruling.”

As news of the ruling spread, Cindy Sanford, a Pennsylvania prison activist, was anticipating her regular afternoon call with Kenneth Carl Crawford III. He is serving a mandatory life-without-parole sentence for his involvement in a double murder at age 15 in 1999.

She expected she would be the one to tell Crawford, whom she considers a son, about the ruling.

Jody Kent Lavy, director and national coordinator at The Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, said many of those affected by the ruling have been on an emotional rollercoaster since Miller as they waited to hear how their states would respond.

The ruling brings greater clarity and hope to them, but work remains to be done, she said.

“I think the challenge is to ensure that the people who are serving these sentences are given meaningful opportunities to present their cases for resentencing or parole,” she said.

Highly skilled defense teams are needed to present the cases that address the mitigating circumstances the Supreme Court has identified, and parole boards and judges need training on what the court has ruled, Kent Lavy said.

“It’s going to have to be a multifaceted approach to ensure these people have the representation they need and the decision makers who are ultimately deciding their fate have all the information they need and aren’t simply rubber-stamping their sentence,” she said.

Shirley Bradford, whose son Otis Daniels has been serving a life-without-parole term in Georgia since he was 16, called the ruling “a blessing.”

“When you’re imprisoned as a child, you go in as a child,” she said. “You’re not able to go to any classes to rehabilitate yourself. You’re not allowed to take any job training skills, because to them it’s a waste of time and money, because he’s never going get out.”

Daniels pleaded guilty to killing one woman and wounding another during a 1998 robbery in southwest Georgia. Bradford said she was waiting to hear what the chances of her son getting a shot at parole might be.

“If you’ve got a 16-year-old at home you would never consider your child to be an adult, no matter what they’ve done,” she said.

Streib doesn’t predict that the decision would result in large numbers of juveniles being set free.

“Symbolically, the ruling is interesting,” he said. “But in fact, whether or not any of these child offenders are paroled is still up to the parole board.”

“It’s great news,” said Montgomery’s cousin Dianne Coleman. She predicted she and her cousin would have a joyful conversation on Sunday, when she makes her regular visit to the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

Henry Montgomery has spent decades in prison since he was convicted in the shooting death of sheriff’s deputy Charles Hurt in East Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in 1963. He was 17 at the time of the murder.

Nine states have abolished juvenile life without parole in the past six years, while others have added review mechanisms that give inmates a chance to seek a reduction in their sentences.

Steve Reba, an attorney who directs the Appeal for Youth Clinic at Emory Law School’s Barton Child Law and Policy Center, said he is hopeful that the next frontier in juvenile justice will eliminate all mandatory minimum sentencing for juveniles because it eliminates the chance to show how a convicted person’s youth played a role in his decision making.

The Miller decision did leave the door open to life-without-parole terms in cases where a teen is “permanently incorrigible,” but emphasized that those cases would be rare — and the Supreme Court restated that in the Montgomery decision. In his dissent, Justice Antonin Scalia said the majority now makes that “a practical impossibility.”

“And then, in Godfather fashion, the majority makes state legislatures an offer they can’t refuse: Avoid all the utterly impossible nonsense we have prescribed by simply ‘permitting juvenile homicide offenders to be considered for parole,’” Scalia wrote.

Streib stays in touch with some defendants he represented years ago, and he said, “I know they’ll get their hopes up.”

“But in some cases the crimes are so horrible that the parole board is extremely unlikely to grant it.”

A lawyer who argued for the state of Louisiana at the Oct. 13 Supreme Court hearing warned afterward that resentencing hearings, if needed, would impose a significant burden on states.

“It would make the state do a fact-intensive resentencing for thousands of offenders who are nonetheless facing a constitutionally valid sentence,” S. Kyle Duncan said.

Sanford said that in the past she would have opposed this ruling, but that her family’s relationship with Crawford has changed her beliefs.

“We just believe Ken is a perfect example of the change that the child can go through,” she said.

Sanford said she doesn’t want to minimize the pain of the victims’ families. And she knows that the process could be long, and not end in Crawford’s favor.

But she still couldn’t wait to tell him the news.

“Today, we want to think positively,” she said.

This story was published by the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange. Sarah Barr, Amy Linn, Katy Reckdahl and Matt Smith contributed. It was updated Jan. 25, 2016, to include comments from Jody Kent Lavy and Shirley Bradford.

*Correction: The subhead on this story, which appears on the home page and other navigational pages on The Lens, originally stated that Montgomery will get a parole hearing. That’s incorrect; he may get a parole hearing, and he could also be resentenced in district court. (Jan. 26, 2016)