Is this another piece whining about how New Orleans is changing for the worse? Is this another burst of weepy “ain’t dere no more” nostalgia?

Yes.

It’s also about the French Quarter: ground zero of New Orleans history and, at least until recently, ground zero in debates over gentrification and the changing character of the city. Today the gentrification debates focus more on neighborhoods downriver from the Quarter, areas which still contain many people who fled the Quarter as the rents got too high. Where will they (we) go now?

The transformation of the city’s oldest neighborhood into a retirement community for the rich and boring is now too far along to stop, but that’s no reason not to cry at the autopsy. “Ain’t dere no more” nostalgia is a genre deeply rooted in New Orleans letters, and it’s never been stanched before by a lack of practical applicability. Sobbing at the funeral won’t bring back the dead, but people do it anyway.

The choice has never been between change or remaining the same. As the saying goes, change is the only constant in urban life. But changes are agreed upon — or not — by people (or, to be more honest, people with money.) The rest of us get to whine.

Lots of little changes add up to total change, and there have been more than a few little changes this year affecting the Quarter. It’s now light years removed from the Quarter I knew growing up.

The smoking ban is one of these changes, I suppose; it definitely changes the ambience of the Quarter’s many bars. But some changes are more sensible than others, and some are arrived at almost democratically. The smoking ban had the support of many New Orleanians, including employees of the affected establishments.

Getting rid of the Confederate monuments is another change that many New Orleanians see the sense in, and I’m one of them. But the main criterion for my decision on whether a change is good or not is economic, and neither the smoking ban nor the removal of Confederate monuments makes the city more expensive, thus driving away its historically low-paid inhabitants.

The genius of New Orleans culture was its accommodation of joie de vivre not just for the rich — for whom the entire country is a playground — but for natives of limited means as well. It might sound hard to believe today, but the French Quarter was cheap to live in until very recently.

Movies are the amber in which we can glimpse the old Vieux Carré. Elia Kazan’s “Panic in the Streets” gives us a look at the place in 1950. Walter Hill’s “Hard Times” shows us the fairly rundown Royal Street of 1975 — remarkably, the film was set in the 1930s, and the structures didn’t look much different 40 years later. Even Clint Eastwood’s “Tightrope,” released in 1984, shows us a functioning farmers’ market and the condemned husk of the old Jax Brewery, before its renovation anchored the new era of a cleaned-up, more expensive Decatur Street.

One of the great ironies is that the Quarter had a lot more families and children when it was far more sleazy. This past week, the Louisiana Office of Alcohol and Tobacco Control revoked the liquor licenses of five bars in the upper Quarter because of suspected drug dealing and prostitution. Who are they protecting?

Back when families lived in the Quarter, prostitutes were a part of the cityscape, particularly along Iberville and upper Decatur. To be honest, as a kid I was a little freaked out by the aggressive street walkers, many of whom were transsexuals.

And the ruins of Jax Brewery were decidedly a hazard, which of course did not stop us from playing in the darkened interior on the way home from school. One day I narrowly missed falling three stories into one of the giant holes left when they removed the brewing tanks. That same day, by coincidence, we were accosted at Jax by heavily armed police. They told us the place was a haven for interstate felons who hopped trains all over the Mississippi valley and came there to hide out.

This is the big dilemma when arguing about gentrification. I’d like to live in a neighborhood where prostitution is more discreet (in bars or brothels rather than on the street) and where condemned structures don’t threaten to collapse on passers-by or cause the deaths of naturally adventurous children. But can I afford it?

Everything before the 1980s brass band revival is viewed with the vague fear that it’s probably a bunch of racist Southern stuff, and we’d best not go there.

We have a nice new amenity in my neighborhood today, the Crescent Park on the riverfront. It’s wonderful to have a formerly closed space open to the public. It’s free, of course, being a public park. But as Daniel Wolff argued in this space a couple of years ago, public parks are actually something you don’t want. Why? Because they attract the wrong element — people with money, who will then see to it that only other people with money will ever be able to live anywhere near the fabulous new park.

Crime is another thing we’d all like to see less of. Or is it? Many older native New Orleanians mutter the cynical hope that good old New Orleans bad guys will eventually scare off the well-heeled newcomers. I believe the dream of a low-crime city — the phenomenon we glimpsed for a handful of months after Hurricane Katrina — might actually be possible. But again I’m afraid I won’t be able to afford it.

The French Quarter is leading the way. In last month’s vote, Quarter residents approved a quarter-cent hike in sales taxes to pay for a more permanent presence of state troopers — just in the Quarter. Frankly, I’d prefer more city cops to troopers; the staties seem to excel mainly at busting prostitutes and roughing up local musicians like Shamarr Allen. But as in other neighborhoods that have agreed to higher property taxes to pay for beefed-up neighborhood patrols, there’s a built-in inequity.

Accepting a higher cost of living in exchange for more police protection is very different from a broad federal or state tax hike that finances improved public services for everyone. The special assessments move well-heeled neighborhoods closer to the suburban dream of a gated community, a barrier that may enhance the safety — and prestige — of those inside, but that relegates the rest of us to the no-man’s land that used to be called middle-class America.

So the Quarter will be a bit safer and a bit more expensive. It will also continue to be less diverse, in terms of race, income, and stage of life. The kids are mostly gone by now, hanging by a thread at the only remaining elementary school in the Quarter, my alma mater, McDonogh 15. Rumors have swirled for years that the School Board will sell the site to real estate developers, and today those rumors seem truer than ever, with the lease of the latest tenant — KIPP New Orleans — drawing to its close.

You used to see old folks in their wheelchairs in the 1200 block of Dauphine Street, across from the kids romping in the wading pool of Cabrini Park, adorned as it was with Bruce Brice’s mural of multi-colored French Quarter children at play. The mural is gone, the wading pool is gone, though a fancy new playground set has replaced the basketball courts. (I guess younger kids are less scary than older ones). And now the old folks are gone, too.

They’d been on the block since Reconstruction. The Maison Hospitaliere was initially built to house indigent Civil War widows, but it continued as a nursing home until 2006. Now it’s been partially razed, partially gut-rehabbed, to make room for million-dollar condos — 10 of them. “We’re confident the market is there,” said the developer, “whether it’s people who are going to make this their permanent home or a second residence.”

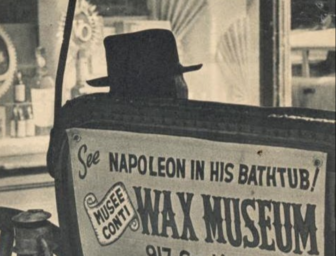

More condos are coming to Conti Street as well, at a site that’s going to go down as one of the most painful “ain’t dere no more” losses. The Musée Conti wax museum, the delight of a couple of generations of Quarterites, will close its doors forever at the end of January. They’ve already sold the building; architects are drafting the condo plans.

The Wax Museum, open since the 1960s, was a unique New Orleans attraction in a number of ways. Many tourist destinations have wax museums, but the star of the Musée Conti was New Orleans history, not the latest Hollywood sensation. The exhibits showcased the spectacular and the creepy, as well as the merely odd scenes from the history of the city. They conveyed the aura of New Orleans as an exceptional place with a special sense of its own mythic identity: Ursuline nuns, Jean Lafitte, Marie Laveau, Madame LaLaurie, Storyville, the 1891 lynching of the Italians at the Parish Prison.

In the cool, darkened halls, the series of three-dimensional scenes, with their life-like wax protagonists, unfolded at whatever pace you wanted to walk. The place was too quiet, and required too much interpretation on the part of the viewer, to compete with 3-D Imax explosions at the World War II Museum or the Aquarium. And many of the historical episodes foregrounded in the museum were dark, even terrifying. Maybe that lack of sugarcoating was too much for today’s parents and school administrators to ever get comfortable with.

You could argue that the framing of the city’s history was technologically as dated as, well, a waxworks. But the charm lay in it being so lovingly presented. The museum was a visual version of a common New Orleans literary genre which we might call “mythography.” It’s a tradition at least as old as Charles Gayarré’s multi-tome antebellum “History of Louisiana,” in which the author acknowledged a bias toward “poetry and romance” rather than “the scrutinizing, unimpassioned, and austere judgment of the historian.” Other hoppers of ore from the same lode include Henry Castellanos’ “New Orleans as it Was” (1895), Grace King’s “New Orleans: the Place and the People” (1921), Lyle Saxon’s “Fabulous New Orleans” (1928) and Robert Tallant’s “The Romantic New Orleanians” (1950). These are very subjective, unscientific histories in which fact is tinged with the magic of myth.

New Orleanians still like to think of the city as a rare and rebellious place that swims against the swift currents of the American mainstream. But the exceptionalist strain in contemporary culture has lost touch with the moody romanticism in which it is rooted. Today’s version is often a one-note obsession with music and the lifestyles associated with it, cuisine, of course, and parading included. Everything before the 1980s brass band revival is viewed with the vague fear that it’s probably a bunch of racist Southern stuff, and we’d best not go there. And of course academia is no friend to more mythical approaches to history, since they’re not scientific and often serve dubious political purposes.

The wax museum was a great reminder that, while every city has a history, a city with its own mythology really is something special. If it were being replaced with anything besides high-priced condos, I would be less despondent, but it’s hard to avoid the symbolism in this particular change: a commemoration, however flawed, of the myths that form our collective identity is being bulldozed so that more retirees from Dallas can enjoy the sanitized ambience of a neighborhood that New Orleanians used to live in.

C.W. Cannon’s latest book is “Katrina Means Cleansing,” a young-adult novel

about Hurricane Katrina. He teaches “New Orleans Myths and Legends” and

other courses at Loyola University.