The mouth of the Mississippi River should be moved north to Port Sulphur or English Turn and communities south of those points eventually will have to be abandoned if other parts of southeast Louisiana are to have a future into the next century.

Those were among the more startling recommendations proposed by the winning teams of coastal engineering and sustainability experts from around the world who took part in Changing Course, a design competition sponsored by Louisiana that kicked off in 2013.

Key features of the plans would represent dramatic departures from the state’s up-and-running Coastal Master Plan, a $50-billion, 50-year vision that has received generally high praise from the scientific community. Experts said their recommended changes should be taken seriously because subsidence and sea level rise will make many existing communities indefensible in the coming decades.

“We want to stress this isn’t something anyone is saying needs to be done soon, but it is something we think will be necessary in the future – so we need to start planning for it now,” said Jeff Carney, director of the LSU Coastal Sustainability Studio.

“This is going to happen. So the choice is, do we get out in front of it over the next 50 years and manage the process, or wait for it to happen to us – wait for the next big storm to wipe out communities, erase the shipping channel in the lower river and throw commerce into chaos?

“The leadership of the state needs to begin discussing these realities openly with residents now.”

Participants were charged with designing long-term plans that could ensure the presence of sustainable coastal wetlands into the next century while also maintaining or improving river commerce and flood protection. The state hoped the global reach of the competition would provide new ideas from the rapidly evolving fields of coastal engineering and science, even as it moves forward with the Master Plan. Twenty-three groups responded, and the three finalists were awarded $300,000 each to refine their presentations. Funding came from a group of philanthropic foundations and Shell Oil.

Although state officials didn’t commit to adopting any of the suggestions, the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers – the major partners in the Master Plan – were on the competition’s leadership committee.

However, Kyle Graham, executive director of the coastal authority, said his agency is investigating some of the specific land-building ideas and computer models that came out of the competition.

The winning plans came from the teams of Baird & Associates, Moffatt & Nichol, and Studio Misi-Ziibi. They included review and participation from the shipping, fishing, and energy industries.

The Baird Team would move the mouth of the river to English Turn and retain the current navigation channel as a deeper slack-water entry to the port. Like the other plans this would also abandon communities along the lower river over several generations.

Like the Master Plan, the winning designs focus on reconnecting the sinking, crumbling coastal wetlands to the freshwater and sediment in the Mississippi River.

However, the Changing Course participants worked with key advantages over the architects of the Master Plan: They were given a 100-year time frame instead of 50, and they were unencumbered by the budget realities, public-review processes and political approval required by state actions. Those points gave them the freedom to let science and engineering guide their decisions.

The three top designs reached consensus on several things:

- The future delta and coastal wetlands along the lower river will be dramatically smaller than today’s because the river doesn’t carry enough sediment to offset the combination of subsidence and projected sea-level rise. As one team member put it: “We won’t have enough mud to fill the deepening holes.”

- The required changes are so vast, expensive and socially disruptive they must take place over several generations.

- The rates of sinking and sea level rise mean communities downriver must eventually be abandoned. The state should begin educating residents now so they can begin discussions on how and when relocations will take place.

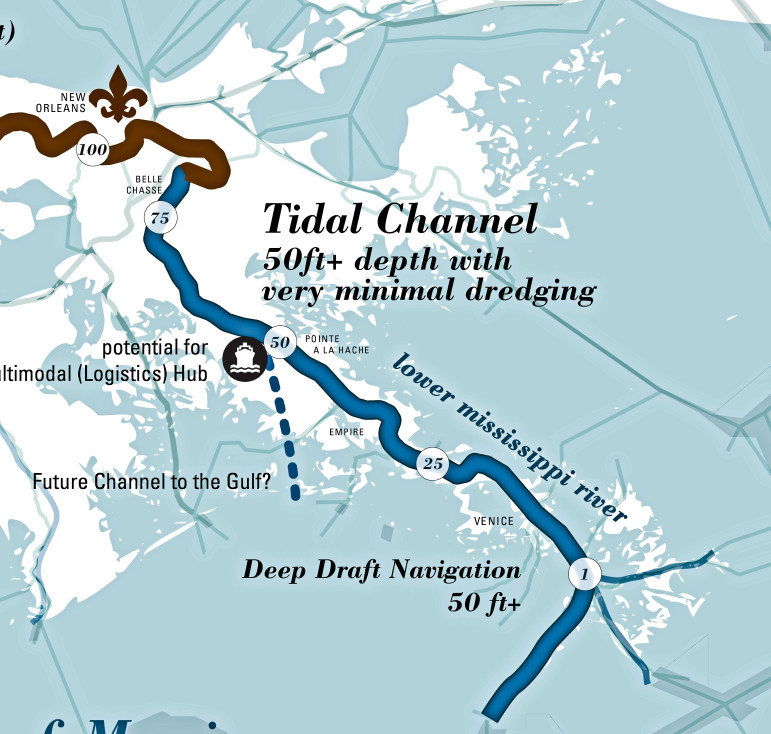

- Moving the mouth of the river north accomplishes several important goals. Sediment that now spreads out across the lower delta’s sinking basins and the nearshore Gulf with little benefit to the coast could be trapped and used for land building. Ships would have a shorter, quicker journey to port facilities. And the threat of river floods would be reduced because there would be a larger outlet closer to the city. The new channel would be dredged to the 50-foot depth soon to be necessary if the port is to remain competitive when the enlargement of the Panama Canal is completed.

- Diversions being considered for the lower river should be cancelled, and new diversions should be planned north of the city. The new locations would be more efficient land builders because they still have enough wetlands that can trap sediment and will be in areas with less subsidence.

- The coastal fishing industry cannot avoid dramatic relocation because major diversions are the only way to build and maintain enough wetlands habitat to supply its target species. Each of the plans hopes to rebuild basins on a schedule that would always result in enough estuarine habitat in some areas for viable fisheries on shrimp, crabs, oysters and fish such as speckled trout and redfish.

Each of the plans include a host of other strategies to build barrier islands, oyster reefs and other natural features to aid in rebuilding and maintaining wetlands.

Effort at saving lower delta futile, designers agree

Some of the suggestions in the plans are not new. In fact, the master plan issued in 2012 stated that realignment of the lower river was “the best of any individual restoration project type” for building land. It recommended further analysis of that idea. Moving the mouth of the river northward would require building structures to redirect the current at that spot. That would cut off most of sediment supply to the rapidly subsiding lower delta.

Some coastal experts have long maintained the master plan has not given enough weight to the impacts on the lower river of subsidence – as much as 5 feet a century for the bird’s foot delta – and sea level rise. In a 2009 paper, LSU researchers Harry Roberts and Michael Blum concluded there is not enough sediment in the river to prevent “significant drowning” of the area. They suggested moving diversions upriver of New Orleans.

Roberts, who was on the Baird team, said a review of the latest research by the teams strengthened those convictions.

“All three of the teams came to the same conclusions that the retreat of the coast and subsidence has outstripped our resources to solve the problem on the lower river,” he said. “I think everybody now realizes we’ve reached the point where you have to use the river’s resources in a big way to combat this – that anything else you do is kind of piecemeal and won’t last.”

Roberts said the final plans also concurred with his 2009 assessment that spending valuable sediment resources trying to build land on the lower delta would be a futile effort.

“Any new wetlands you build down there will eventually be isolated from the rest of the coast by subsidence and sea level rise,” he said. “By moving diversions north, we’ll be building wetlands in areas with less subsidence and that we can defend in the future against sea level rise.”

Rather than criticize the master plan, team members said their visions expanded on ideas and results already evident in what the current plan hopes to accomplish.

For example, even with its claim to build more land in aggregate than the state loses by 2060, the Master Plan forecasts a smaller coast and delta. It also has no plans to save the bird’s foot delta.

But the design teams go much farther than the Master Plan in making the case for dramatic changes in the river’s lower channel, in the use of diversions and the need to relocate communities.

The Baird team would move the mouth of the river to English Turn – within sight of New Orleans — then maintain the existing shipping lanes through Southeast Pass.

The Moffatt-Nichol and Studio Misi-Ziibi groups would move the mouth to Port Sulphur and West Pointe a la Hache, respectively. They would dredge new shipping channels either west into Barataria Bay or east into Breton Sound.

Each would result in the communities in lower Plaquemines Parish being connected to the rest of the state by bridges or ferryboats – and then only as long as those landscapes remained above the rising Gulf.

Team members said the engineering and design work for the plans was the easy part, and the toughest jobs would be finding the political will even to begin the discussions their solutions should provoke.

Steve Cochran, the Environmental Defense Fund’s director of the Mississippi River Delta Restoration coalition, which also helped manage the competition, said any chance at sustainability for the region would involve having discussions about these major changes coming from the communities involved — not being handed down by governments.

“There’s been some incredible thinking coming out of the process, but the real value will be if we can have people take a look at what the future holds, and say, ‘OK, this is what we need to start thinking about. This is where we want to be in the future, and this is how we’re going to get there.’ ”