The new $14.5 billion levee system encircling New Orleans includes some of the latest engineering advances and has been deemed the city’s best ever.

But, as expected, the delta it sits on is sinking so fast that most of the levees will have to be raised over the next 10 years to keep the area qualified for federal flood insurance.

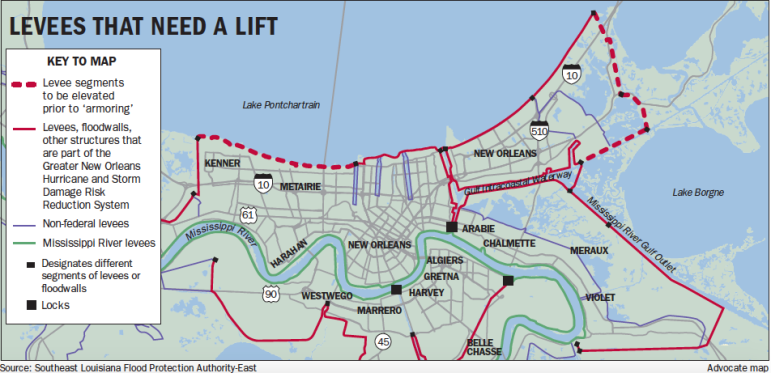

That process began Wednesday, when the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East’s coastal advisory committee presented a list of levee sections that it recommended lifting in the near future.

The full board approved that resolution Thursday and decided to start planning exactly how it will raise the levees.

Lifting these levee sections would cost up to an estimated $37 million, with up to $17 million spent lifting the all of the levee sections along the Lake Pontchartrain shoreline in Jefferson Parish. This portion could cost as little as $10 million if it is determined that the additional height would not require stability berms.

The other $20 million would go toward levee lifts in eastern New Orleans.

None of the levee sections is now below the heights required to meet the system’s standard of protecting against the 100-year storm – a storm with a 1 percent chance of happening every year – but the sections could be below these heights as soon as next year. The early start is a cost-saving measure.

The Army Corps of Engineers is preparing to spend about $34 million to armor the protected side of the levees with synthetic matting and new turf, a job that will reduce the risk of levee collapse from overtopping during storms larger than the 100-year level. Raising a levee section after that job is done would mean removing and then replacing the matting and turf at local expense, which is why the committee recommends lifting the levee sections before armoring them.

Armoring the levees now and lifting them later would make the levees stronger sooner, but the levees would be just as weak when it comes time to remove the armor during the lifting process.

“Do you take the risk today, or do you take the risk two years from now or three years from now or five years from now?” asked Bob Turner, regional director of the levee authority. “If you’re going to raise the levee, there’s going to be a time when you’re not going to have armor on it, and that risk is going to be there no matter when you do it.”

Waiting to lift the levee sections until after the corps adds the armor would make this situation even more dangerous. During the two or three years required to armor the levees, they will have sunk to even lower levels. When it came time to strip the armor and lift the levees, they would be both weak and short.

Since the flood authority knows it will need to raise most of the system before the next 10-year FEMA certification for flood insurance in 2025, it hopes to save the cost of re-armoring the levees by raising them now high enough to offset expected subsidence.

“This is something we’ve been planning to do as soon as the corps committed to the armoring,” said Stephen Estopinal, president of the flood authority. “It’s just taken us a little longer to get all the ducks in a row.”

Those ducks included reaching agreement among the corps, the levee authority and the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority over just what sections needed to be lifted and how high. Although engineers know the area is sinking at one of the fastest rates of any large coastal landscape on the planet, the rate of subsidence is not uniform across the region, or year to year.

The corps developed estimates for subsidence on every section of the system, but the complex nature of the delta soils makes that a best-guess process. For example two sections have already had to be raised even before they were turned over to the flood authority.

That uncertainty weighed on the decision of how to proceed with these early, cost-saving lifts, Turner said.

“We want to give priority to the sections we know are already subsiding at a faster rate, to keep them from falling behind design requirements,” he said.

The authority knows there will be no such savings for the future lifts that will be necessary.

“If you live here, you know we’ll always be sinking, so there will be other lifts required in the future,” Estopinal said. “When those come around, we’ll have to rip out that armoring and pay to replace it.

“It’s all part of the cost of living here.”

This story was updated to reflect the board’s vote on Thursday to move forward with engineering plans. (May 21, 2015)