At almost any time, the sky over a New Orleans neighborhood can quickly change from blue to black as a storm moves in, unleashing window-rattling thunder and dense sheets of rain. In 20 minutes, the deluge can swamp streets, with water rising over lawns and inching toward front doors.

But 30 minutes after the last drop falls, the city’s huge pumping stations can have those streets dry again, the only evidence of the downpour being the steam rising from concrete, baking again under the sub-tropical sun.

Locals may celebrate that efficiency, but Roelof Stuurman, a visiting Dutch groundwater specialist, shakes his head in disgust when he thinks of that rapid and regular wet-to-dry cycle in New Orleans.

“You spend your money trying to get every last drop of water out of your city, when you should be trying to keep some of it in,” Stuurman said. “You have this serious problem, and no one is in charge of it – instead you’re making it worse.”

“That’s what we’ve been doing by fighting water instead of trying to live with it. We’ve been hurting ourselves.”—David Waggoner, co-author of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan

That problem is subsidence – the steady, costly and dangerous sinking of the city caused by the drying of the delta soils it rests on. It turns out New Orleans, known for its epic battles to keep water outside of its levees, is also threatened by keeping too little water in.

A city that prides itself on embracing contradiction is now waking up to this one: The levees and pumping stations it has spent nearly 300 years perfecting to guard against external threats have also been the catalysts allowing an unseen enemy below to savage its budgets and cloud its future.

“When we settled here, the land under us was like a sponge that contained a lot of water,” said David Waggoner, an architect and co-author of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, which aims to change the city’s relationship with water. “And what happens to a sponge when you dry it out? It shrinks.

“That’s what we’ve been doing by fighting water instead of trying to live with it. We’ve been hurting ourselves.”

The evidence is seen across the city

The wounds are visible everywhere: roller-coaster streets pocked with tire-eating potholes; homes tilted and twisted like subjects in Michalopoulos paintings; fractured driveways and sidewalks; lawns that no longer reach front steps, and a drainage system with piling-supported main lines that can be higher than the neighborhoods they are suppose to keep dry.

Yet an even more troubling future is written on elevation maps of the city. Half of the metro area has already been pulled below sea level, and it continues to sink even as the seas rise at a record pace due to global warming.

Sixty-one percent of metro-area residents now live lower than the surface of the lakes and wetlands pushing against the levees, according to Tulane University geographer Richard Campanella, and that number is only going to increase in the years ahead.

Many residents understand the price of protecting the area from hurricanes – a new $14.5 billion levee system and soaring flood-insurance rates – but few understand how the sinking land adds to the their daily cost of living as well as the region’s future viability.

Figures in the Urban Water Plan and estimates from city and state officials show a staggering subsidence bill over the next 50 years:

-

$2 billion in structural damage to homes and buildings. That’s $41 million a year.

-

As much as $1.5 billion lifting and re-armoring sinking levees so they remain certified for subsidized flood insurance.

-

$8 billion in flood damage due to rainfall, or $160 million a year.

-

Street replacement rates that are six times the national average: it costs $7 million a mile in New Orleans compared to $1.7 million in other urban areas. The extra cost is the amount of subsurface work required due to subsidence, according to the city’s Department of Public Works.

-

Much of the more than $24 million the city spends annually on sewer and water line repairs is related to subsidence.

An uneven foundation for the city

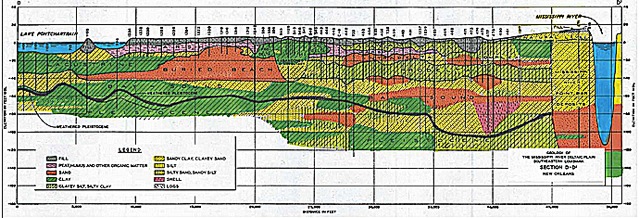

The underlying reason for those costs is made clear by an image Stuurman is holding. It shows a cross-section of the earth beneath New Orleans displaying different soil types in different colors. It looks like a Jackson Pollack painting. Colors start and stop, rise and fall in no discernible order. The chaos covers every inch of the 150 feet between the city’s streets and the first hard rock.

“You’ve got highly organic material like marshes, then clays, then beach sands — and in some places a mixture of all those,” said Bill Gwyn, a local engineer who has worked in these soils for decades. “So there really isn’t any average you can go with over distance.

“It is very complicated and challenging.”

It’s all the result of the region’s geologic history. The Mississippi River built this delta with annual floods over thousands of years, each of which may have carried different materials. Later, deeper floods might have covered surface features that grew on the delta. That produced the wild weave of different soil layers beneath the metro area.

So the sinking and expansion can vary from one end of a street to the other, from month to month.

Most of that movement is controlled by the water table – the amount of moisture in the soils. The higher the water table, the slower the rate of subsidence.

Originally, the water table under New Orleans stayed high thanks to an almost annual soaking from Mississippi River floods. But when levees were raised to protect the city from those floods, the water table started dropping and the soils began to drain, dry and sink. That problem was magnified when development spread blankets of concrete and asphalt across the landscape, reducing the ability of rainfall to recharge the water table.

New Orleanians live in a city that gets an average of 60 inches of rain a year, yet they know the area’s rare droughts can cause expensive problems as well: sink holes develop in streets, houses begin to list like leaking ships, cracks spider across walls, and doors start sticking in their jambs as homes begin to move with the ground beneath them.

But for a population living in a bowl, fear of flooding from frequent torrential rains was always the greater concern, and higher priority. The result is a vast storm-water drainage system featuring some 1,300 miles of subsurface pipes leading water to a series of deep outfall canals linked to 23 pumping stations which rank among the largest in the world.

And they’re always working.

“Some of those lines just continuously drain water from the soils beneath the area and into the canals, even when there is no rain,” Waggoner said. “So there is this constant tapping into the water table.”

Can a pumping system be too efficient?

In fact, that move-it-out-quickly drainage system is now recognized as a contributing factor to more flooding, not less. Speeding great volumes water to the canals can quickly overwhelm the capacity of those huge pumps to stay ahead of torrential rains.

And as the land continued to sink due to the draining of the water table, the flooding threat became worse in some sections of the city because they are now below sea level. Because the drainage system depends on gravity to move water to the pumping stations, the canals and the major pipes leading to them are supported by pilings to prevent them from sinking below the level of the pumps. But some of the streets and homes around those lines are not on pilings, and they have sunk below the system designed to keep them dry.

That’s one reason some of the city’s major roads — such as Nashville and Napoleon avenues – seemed to be on ridges several feet above the above the homes around them. They have been built on top of huge drainage culverts that rest on pilings.

“I know this sounds counter-intuitive to a lot of people but the drier we get, the more vulnerable we become to flooding and a whole list of other damages,” Waggoner said. “We need to consider water as our friend.”

To the surprise of many, a city best known for resisting change is beginning to wrap its arms around the new idea that it must embrace water as an ally, rather than fighting it like an enemy. Providing more space for this friend to live inside the levees will help maintain the water table, and will mean less of it invading homes during heavy rain events.

That acknowledgement began to turn into citizen action in 2013 with the release of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, which was funded by state and federal grants. Developed by Waggoner’s firm in collaboration with water management experts from the Netherlands and around the world, the plan presents a $9 billion vision of how the Crescent City can turn its age-old enemy into a friend by raising the water table to help reduce subsidence.

It proposes doing that not only by keeping water inside the levees, but actually showing it off.

The 82 miles of open drainage canals that form concrete scars across the cityscape when empty would become manicured bayous lined with recreation paths and holding water 24/7. Empty lots left by Katrina that now collect only weeds and debris would become rain gardens – temporary reservoirs that can reduce the speed and amount of storm water rushing toward the pumps during heavy downpours.

“We’re talking about a really difficult juggling act – keeping enough water in to meet those goals, but making sure we don’t have flooding.”— Joe Becker, Sewage & Water Board

But the change would be more than skin deep. Streets and parking lots would be surfaced with materials that allow water to seep into the soils below. Homes and buildings would have rain barrels that trap runoff from roof gutters then let it out slowly over time. New development would require stormwater management plans to account for their impacts on the system.

All of those features would be linked to the overriding goal of maintaining the critical element in fighting subsidence — the water table. A system of water table monitors would be established across the metro area, giving officials the ability to determine how much water can be held in each rain event. New Orleans might join cities such as Galveston, which created a Subsidence District to regulate activities which could affect their sinking lands.

Advocates of the plan say New Orleans could be become the Amsterdam of North America, a city living with water, not against it. Indeed, the plan makes such economic and engineering sense traditional opponents of dramatic change — government agencies and the business community — have signed on.

Yet all agree this won’t be easy, or happen quickly. There’s the big problem of finding $9 billion.

And the goal of re-plumbing the metro area to raise the water table while ensuring homes remain dry isn’t just a huge engineering challenge. It will also try the confidence of residents.

“We’re all for green infrastructure and the (water) plan, and we’re trying to implement this as we move forward wherever we can,” said Joe Becker, general superintendent of the Sewage & Water Board of New Orleans. “But we’re talking about a really difficult juggling act – keeping enough water in to meet those goals, but making sure we don’t have flooding.

“I can tell you this: I’ve never had anyone call to complain that the streets drained too quickly.”

Could you add a pop-out higher definition version of the subsidence illustration?

Yes, the water table is lowered in part because of leaky drain and sewerage pipes that allow water in. But we also have leaky water pipes that spill water into the ground througout the city. I wonder which is greater? The water leaking in or the water leaking out?

The picture of the half-seen woman at Canal and Jeff Davis makes me wonder if the resulting poor visibility there due to subsidence was a contributing factor in the death of the cyclist there this morning. There are multiple ways that poor water management impacts public health and safety.

This is last paper edition of the old SCS, now NRCS, soil survey of Orleans Parish. They’re a branch in the US Dept of Agriculture. The URL goes to the whole survey. I just pulled out one page covering the Allemands soil under most of the urban part of the parish.

http://www.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_MANUSCRIPTS/louisiana/LA071/0/orleans.pdf

Anybody see anything in this soil survey which suggests this type of soil change is reversible? Especially by adding or retaining water?

If the image does not appear, I tried to post page 12, PDF 22 of 100.

As best I can tell, it appears to be only soil borings. I, too, would like a larger, readable image but to get subsidence you’d need elevations over time. There’s a bunch of geology studies about Orleans Parish. If interest develops I’ll post a few references.