Twenty months after the mass shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, some would say little has changed when it comes to guns in America.

Others would say everything has.

Flurries of gun-related legislation and renewed national attention on the topic have not been enough to change federal gun laws. The National Rifle Association, still the most powerful entity in the war over guns in America, no longer has a monopoly on the debate.

A resurgence of the gun control movement is challenging the status quo, while groups to the right of the NRA are also growing. Nonprofit organizations on each side are battling like they haven’t in years, all trying to shape the country’s politics and win over the American people.

But in spite of the evolving landscape, no progress in either direction is certain.

The gun control movement was nearly $285 million behind the gun rights movement in 2012 revenue raised, before Sandy Hook. Today, it is playing catch-up to the money, membership and political savvy of its opponents as the NRA works to maintain its dominance.

“For the first time ever, there is a grassroots group that is going toe-to-toe with the gun lobby. That’s never been the case before.”—Shannon Watts, Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America

Over the course of this year, News21 reporters, videographers and photojournalists traveled across the country to assess the state of the gun debate, its evolution and emerging issues.

With new groups, a revamped strategy, more money and unprecedented collaboration, the gun control movement has made headway. Organizations like Everytown for Gun Safety, the group backed by former New York City Mayor Michael Bloomberg, say they are moving the needle.

“Now, for the first time in our country’s history, there is a well-financed and formidable force positioned to take on the Washington gun lobby,” said Shannon Watts, founder of gun control group Moms Demand Action for Gun Sense in America, speaking at an Everytown event on Capitol Hill in May.

Whether that is possible remains to be seen.

The NRA is strong financially. Its budget has consistently hovered well above $200 million in revenue in recent years and it has cultivated a highly organized grassroots base for more than a century.

As the gun control movement organized in the wake of Sandy Hook, the gun rights movement’s membership boomed. Groups more conservative than the NRA, like the National Association for Gun Rights, are growing. State legislatures across the country passed laws expanding gun rights. The NRA has focused on broadening its appeal.

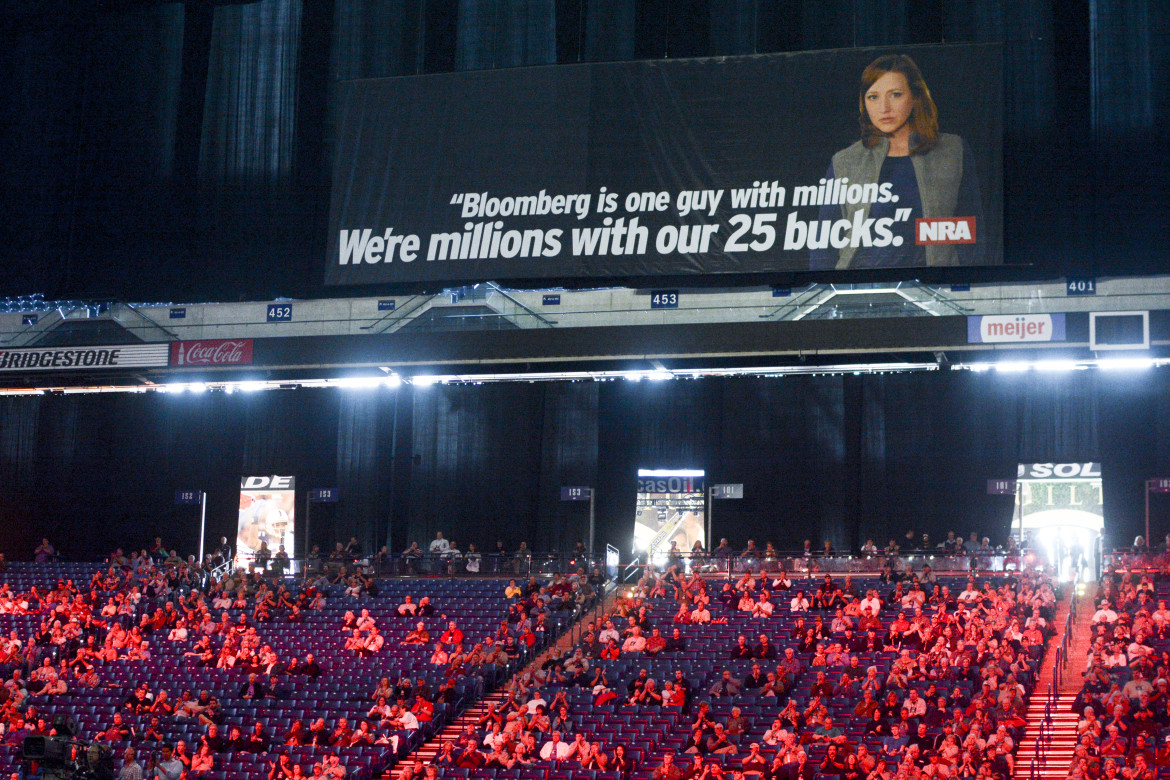

The NRA frequently targets Bloomberg, who donated $50 million to Everytown in April, though the amount is a quarter of what the NRA raises each year.

“Mr. Bloomberg, you’re an arrogant hypocrite,” said NRA Institute for Legislative Action Executive Director Chris Cox at the organization’s annual convention in April. “Stay out of our homes, stay out of our refrigerators and stay the hell out of our gun cabinets.”

“When the person’s a member of the NRA, most people know what that is. It speaks volumes of how they stand on issues, and it’s respected or hated by almost everybody.”—Brad Leeser, member of the NRA and Gun Owners of America

With its near-mythical presence as a political lobby, the NRA is still the best-positioned player in the debate by far, bringing in and spending hundreds of millions of dollars on its broad range of programs. Though its grip on Congress has loosened somewhat, it still isn’t letting major federal legislation through or relinquishing its influence on state politics.

An amendment expanding background checks came to a vote in the Senate in April 2013, something gun control advocates saw as a victory. It didn’t get enough votes to pass.

The NRA began as a firearms education organization and sportsmen’s club in 1871 and didn’t become involved in politics until the 1970s. When it did, however, it had a built-in base of support. It has worked to build strong ties with members of Congress to back its lobbying and political efforts. Today, the NRA says it has 5 million members.

Around the same time the NRA entered politics, the group that would eventually become the Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence was founded. It attained a high profile following the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan, in which Reagan press secretary James Brady was shot and partially paralyzed.

Its advocacy work in the ’80s and ’90s culminated in the passage of the Brady Act — which mandated federal background checks on people buying firearms — and the now-expired assault-weapons ban, both signed by President Bill Clinton in 1994.

About this projectThis week The Lens is publishing stories about the battle over gun rights and regulations around the country. These stories are part of a project produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 program.For the complete project “GUN WARS: The Struggle Over Rights and Regulation in America,” visit gunwars.news21.com

In 1999, the Columbine High School shooting led to a resurgence of gun control advocacy. Like today’s movement, it had a billionaire benefactor in Monster.com’s Andrew J. McKelvey and a mother-led group, the Million Mom March. After a handful of state legislative victories, the movement fizzled.

This was the landscape when a spate of recent prominent mass shootings began: Virginia Tech in 2007; Tucson, Arizona, in 2011, in which then-Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, D-Ariz., was shot; the Aurora, Colorado, movie theater shooting in 2012; and then, Newtown.

The Sandy Hook shooting touched off for the gun control side what Everytown Director of Strategy and Partnerships Brina Milikowsky called a “once-in-a-generation moment of great transformation.”

The day after the shooting, Watts founded Moms Demand Action; a few weeks later, on the second anniversary of the Tucson shooting, Giffords and her husband, Mark Kelly, started Americans for Responsible Solutions.

In December 2013, Moms Demand Action formed a partnership with Mayors Against Illegal Guns, a group founded in 2006 by Bloomberg and former Boston Mayor Thomas Menino. In April, Everytown became an umbrella organization for the two other groups. Today, Everytown says it has 2 million members.

“Twenty years ago, Brady was the only game in town. And now there’s unprecedented resources and attention being focused on this issue, so we’re not a voice alone in the wilderness anymore,” said Dan Gross, president of the Brady Campaign.

In fact, there is a profusion of gun control groups, including many on the state level.

November’s congressional elections — the first major election since Sandy Hook — could provide a barometer for the political gun wars.

Some groups, like Moms Demand Action and the Brady Campaign, say they can now compete with the gun lobby. Others, like Giffords’ ARS, say they want to match the NRA but are still too new to have a comparable budget.

With new strategies, groups like the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, founded in 1974, think they will “be a force for decades to come,” said Ladd Everitt, the group’s director of communications.

$301 millionRaised by the top six gun rights groups in 2012$16 millionRaised by the top six gun control groups that year

But tax filings show the top six national gun rights groups brought in close to $301 million in revenue in 2012, while six major national gun control nonprofits raised just more than $16 million.

The dollars are hard to track. The most recent tax filings available are from 2012, so they don’t reflect any changes that have occurred since Newtown, including Bloomberg’s $50 million donation to Everytown. Nonprofits are not required to disclose information about their donors.

Because Everytown, Moms Demand Action and Americans for Responsible Solutions are so new, their tax forms are not available yet.

$18 millionRaised by the NRA PAC in first six months of 2014$17.5 millionRaised by Americans for Responsible Solutions PAC

However, when it comes to campaign spending, the political action committees on the two sides are neck-and-neck for 2014.

As of June 30, the NRA PAC had just more than $18 million in receipts and the ARS PAC had almost $17.5 million. ARS had spent nearly $8.5 million; the NRA had spent nearly $2.7 million, according to filings with the Federal Election Commission.

With some groups’ finances remaining a mystery, the numbers are inconclusive. In spite of their claims, gun control groups’ ability to compete financially remains questionable.

“We don’t have as much evidence as people sometimes think we do that you can sort of throw money at your cause and get your way,” said Matt Grossmann, a political science professor at Michigan State University. “In fact, that hardly ever works, especially for advocacy groups.”

Much of the NRA’s power is found in its passionate and faithful membership base.

“Their members are very highly trained in grassroots campaigning, so because of the emotional connection to guns, they are easily activated, and that is certainly a plus on their side,” said Karen Callaghan, a political science professor at Texas Southern University who is writing a book on the NRA.

Their members are loyal and, often, lifelong. For many, the organization offers a mark of identity.

“When the person’s a member of the NRA, most people know what that is. It speaks volumes of how they stand on issues, and it’s respected or hated by almost everybody,” said Brad Leeser, 58, a member of the NRA and Gun Owners of America in Moorhead, Minnesota.

Gun rights voters tend to be single-issue voters, meaning they prioritize gun rights over all other issues. Gun control supporters, on the other hand, tend to be less driven by the one issue.

“People on the other side of the debate, it’s a more diffused group, and so I think they’re disempowered for that reason,” said Kathy Kiely, managing editor of the Sunlight Foundation, a nonpartisan open-government nonprofit.

In July, the NRA started its 2014 “Trigger the Vote” campaign, an effort to get pro-gun voters to register before the November election. When Everytown was founded, it launched a “gun-sense voter” campaign, which aims to get “voters to consider gun-violence prevention as a number-one issue that they vote on,” said Jennifer Hoppe, program director for Moms Demand Action.

“The NRA and the gun lobby have done an amazing job over the last 30 years … changing hearts and minds at every level up to the Supreme Court,” said Shaun Dakin, a volunteer who works with organizations including Moms Demand Action and the Brady Campaign. “Now the gun-violence-prevention movement has figured that out … Washington, D.C., will change when the culture changes and when they see people actually voting based on any particular issue.”

Building a grassroots effort is part of the gun control movement’s attempt to attract supporters and compete with the NRA.

That was Watts’ goal in founding Moms Demand Action, which the Indiana mother of five modeled after Mothers Against Drunk Driving. It became a leading grassroots gun control organization and now has chapters in all 50 states.

“For the first time ever, there is a grassroots group that is going toe-to-toe with the gun lobby. That’s never been the case before,” Watts said in an interview in May.

Moms Demand Action’s strategy includes calling legislators, holding rallies — like a June march across the Brooklyn Bridge — and putting pressure on corporations and politicians through social media.

This type of organization is seen in the movement as a whole. The groups have begun to collaborate to move closer to a united front similar to that of the NRA membership base.

Each group plays a specific role, though almost all of them focus on political advocacy at the federal and state levels. The major national groups have a weekly conference call to discuss priorities and plans. Combined, the groups’ strategy covers legislation tracking, legal work, data collection and research, gun-safety education, work with survivors and more.

“There’s never been a point in history … where this movement’s been more unified,” Everitt, of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, said. “There’s a lot of mutual respect in our movement and even love.”

The newcomer groups are joined by more established organizations like the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, the National Gun Victims Action Council, the Brady Campaign and Brady Center.

There is no clear leader in the movement. Once the most powerful, the Brady Campaign sees itself as a gathering point for others now, but collaboration, not star power, is the key, Gross, president of the Brady Campaign, said.

Everytown, the newest player, has perhaps the biggest presence in the news and is the largest of the advocacy groups. Milikowsky says the group leads in research, investigation and thought, but it doesn’t view itself as the leader.

“The only way we’re going to overcome the corporate gun lobby, the only way we’re going to change deeply entrenched social norms, is not to be about any one organization but be about the American public,” Gross said.

Among the gun rights groups, the NRA overshadows other organizations, but many groups want better collaboration.

“We work together when possible, but we don’t always communicate as well as we probably should,” said Alan Gottlieb, chairman of the Citizens Committee for the Right to Keep and Bear Arms and the founder of the Second Amendment Foundation.

“There’s never been a point in history … where this movement’s been more unified.”—Ladd Everitt, Coalition to Stop Gun Violence

Luke Wagner, a grassroots activist who is now the board president of the Colorado Second Amendment Association, said he works to develop ties with other gun rights groups.

“We don’t have to be intrinsically tied to one another. We don’t have to take instructions from one another. But we do have to be able to talk to one another and at least be sure we’re all on the same page,” Wagner said.

Though some groups want more collaboration, gun rights organizations positioning themselves as alternatives to the NRA have grown financially in recent years.

Groups like Gun Owners of America, which opposes all gun control measures unequivocally, and the National Association for Gun Rights, a newcomer that is blatantly anti-NRA, are trying to challenge the older organization.

NAGR’s revenue grew 16 times from 2009 to 2012, an increase unparalleled by fellow gun rights organizations. Gun Owners of America’s revenue grew from about $1.8 million in 2011 to $2.4 million in 2012.

“The NRA has taken gun owners’ money and more importantly, their trust and used it to support those who have a horrible record when it comes to gun rights,” according to one NAGR press release. The group did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

In May, the NRA called the tactics of another gun rights group, Open Carry Texas, “downright weird.” After protest from the group, which carries long guns in public to protest the Texas ban on the open carry of handguns, the NRA pulled the release from its website and replaced it with a message of unity.

The NRA did not respond to requests for comment.

For advocates like Nicki Kenyon, a writer for Jews for the Preservation of Firearm Ownership and a former editor of an NRA magazine, the gun rights movement’s theme is unity of mission, if not unity in tactics.

“We may go about it in different ways. We may disagree on the tactics. But overall, we are an inclusive and we are a cohesive group of people whose only purpose is to protect our rights and freedoms,” she said.

But these groups are still small players compared to the NRA.

“The NRA is seen as the voice of gun owners. It doesn’t necessarily need much help,” said Grossmann, the Michigan State University professor.

Modern gun rights advocacy experienced a turning point after the Supreme Court ruled in District of Columbia v. Heller in 2008 that the right to bear arms is an individual right, not limited to those serving in a militia.

The decision overturned handgun bans on state and local levels, and groups like the Second Amendment Foundation followed it with their own lawsuits to reverse gun control measures in major cities like Chicago.

It brought a new sense of security to gun rights advocates.

“It’s having a huge impact, and the other side will … deny it or try to spin it a certain way, but they know they’re losing,” said Philip Watson, director of special projects for the Second Amendment Foundation.

After Heller, the NRA began opening up to new demographics, said Callaghan, the Texas Southern University political science professor.

In the last few years, it has launched social media campaigns aimed at millennials, women and minorities. It recently debuted a show on its website hosted by a young black gun enthusiast and has six social media accounts aimed just at women.

Both sides of the debate want to reframe the conversation to use less loaded language and portray their stances as common sense.

Last year in Colorado, voters recalled some legislators who passed a package of gun control laws. The campaign was led by a citizen movement called the Basic Freedom Defense Fund.The NRA eventually joined the campaign, but it was spearheaded by the grassroots activists, something that often happens at the state level.

Americans for Responsible Solutions is one of the groups trying to depoliticize the debate. Giffords and her husband, both gun owners, hoped to establish a presence that would counterbalance the NRA while welcoming gun owners, said Mark Prentice, the group’s press secretary.

“It’s about staking a place in the kind of moderate, reasonable middle where most people are on this issue,” Prentice said.

But what is described as common sense for one side is not common sense for the other.

For example, many gun rights advocates portray “stand your ground” laws, which allow people to use deadly force in self-defense instead of retreating, as common sense; gun control groups oppose it. Gun control groups say expanding background checks is common sense; gun rights groups disagree.

Mental health may be the one area that has the potential to be a meeting ground.

The NRA has supported mental health legislation in the past, like the 2007 law meant to improve state reporting to the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS), which includes the reporting of mental health records. The Brady Campaign also worked to pass that bill.

In May, a combination mental health and domestic violence bill was introduced in the House by Democratic Reps. Mike Thompson of California and Elizabeth Esty of Connecticut, whose district includes Newtown. It is still in committee.

In the same month, an amendment to increase funding for NICS by $19.5 million in 2015 passed the House, but the Senate has not taken it up. The amendment’s passage was seen as a victory by the gun control movement – its single federal legislative success since Newtown – but NICS funding will not actually increase unless the bill passes the Senate.

The gun control movement also wants legislation addressing domestic abuse and background checks. Advocates still hope for expanded background checks that would include sales online and at gun shows. A bill like that failed in Congress last year.

Rep. Carolyn McCarthy, D-N.Y., whose husband was killed in a commuter train shooting in 1993, has been a vocal gun control advocate in Congress since the 1990s.

“So many members in the House and the Senate started to stand up and speak, so there’s so many more voices out there today than there was even 10 years ago,” McCarthy said at a February Moms Demand Action news conference on Capitol Hill.

“We went through at least a decade, if not more, where we were not political enough, where PACs we once had that were raising money … folded. We didn’t have a financial presence in elections,” said Everitt of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence. “We weren’t playing hardball.”

But given gridlock in Congress, both sides are fighting battles on other fronts, particularly in the states.

“We’ve shifted some of our priorities, and while we’re still leading the fight in Congress to strengthen our federal gun laws, we are doing more and more advocacy work at the state level and working to strengthen state gun laws,” said Everytown’s Milikowsky.

Six states passed laws this year to help remove firearms from domestic abusers. In Minnesota, Everytown helped draft the bill.

Since the Heller ruling, the NRA has helped pass laws regarding concealed carry of guns, self-defense and “stand your ground,” often fighting multiple battles on the state level, said Callaghan, the political science professor. Grassroots gun rights groups often help or launch their own legislative campaigns.

Last year in Colorado, voters recalled some legislators who passed a package of gun control laws. The campaign was led by a citizen movement called the Basic Freedom Defense Fund.

The NRA eventually joined the campaign, but it was spearheaded by the grassroots activists, something that often happens at the state level.

As the political tug-of-war continues, an indicator of the future of guns in America is elusive. Many are looking to the 2014 elections for a hint.

The NRA’s Cox said on an NRA commentary show that the upcoming election is crucial.

“There’s no question that what we do between now and November is critical to the survival of the Second Amendment and the freedoms we all fight so hard to protect,” Cox said.

The NRA rates candidates and endorses them through its PAC. According to the fund, the rankings are based on voting records, public statements and responses to a questionnaire, the contents of which the NRA does not release publicly.

The association worked on 271 campaigns for Congress in 2008 and says it won 230 of the races, according to its website. Voters can print out “personal voting cards” from the website that list the candidates and mark which are supported by the NRA.

In July, Everytown sent out a questionnaire to every candidate for Congress. It is similar to the NRA’s, but unlike the NRA, Everytown released the questions to make its process transparent. Milikowsky and other representatives would not say whether the group will make election endorsements, nor would they say what it will do with the survey results beyond publishing them.

Prentice, of Americans for Responsible Solutions, believes the issue of guns is going to be increasingly important in elections, and said his organization sees it as an obligation to highlight the issue and the candidates’ stances in campaigns around the country. The group doesn’t donate directly to candidates, but plans to channel money into ads supporting certain candidates.

“What’s most important is the people who have been champions on this issue already and [who] put their necks out there get to return to the U.S. Congress,” Prentice said.

“The election is going to be a bare-knuckles street fight,” said NRA Executive Vice President and CEO Wayne LaPierre at the organization’s convention. “They’re going after every House seat, every Senate seat, every governor’s chair, every statehouse that they can get their hands on.”

Jacob Byk contributed to this story. He is the News21 Dix/Oliver fellow.

This report is part of the project titled “Gun Wars: The Struggle Over Rights and Regulation in America,” produced by the Carnegie-Knight News21 initiative, a national investigative reporting project involving top college journalism students across the country and headquartered at the Walter Cronkite School of Journalism and Mass Communication at Arizona State University.

Share your feedback on this reporting.