Stephen Estopinal, an engineer on the board of the Southeast Louisiana Flood Protection Authority-East, says he has a concern that “keeps me up at night.”

What worries him is the speed with which land beneath the levees and floodwalls protecting the metro area from storm surge is sinking.

New data from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration is not going to make it any easier for Estopinal to get to sleep.

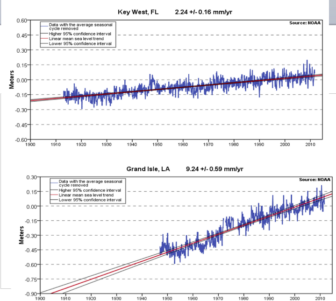

The federal agency charged with keeping track of sea levels, NOAA says Grand Isle has lost 1.32 inches of elevation to the Gulf of Mexico in the past five years alone — a rate of subsidence about four times faster than any other coastline in the lower 48 states, and one of the highest on the planet.

“You might start out with something that’s accurate, but the way this land moves, you’re not going to be accurate a few years later.” — Stephen Estopinal

The rate is so high because the entire southeast portion of the state is sinking while seas are rising worldwide due to global warming. When subsidence is combined with sea level rise, the result is called relative sea level rise.

The latest update only confirms Grand Isle’s nation-leading average of 9.24 millimeters (.363 inches) per year over the past 65 years, or about three feet per century, said Steve Gill, a chief scientist at NOAA. By contrast, Key West, less subject to subsidence, has been succumbing to rising seas at a rate of just 2.24 millimeters per year, according to federal charts of high tides kept over many decades at selected coastal stations.

And the National Climate Assessment, a federal study released this week, indicates only more problems ahead for Louisiana’s coast. The assessment predicts sea level rise will continue at current rates if greenhouse gas emissions — which drive the warming trend — are not curtailed. Worse yet, if those emissions continue to increase, as they have for a century or more, sea level rise will also increase, the assessment said.

It was all bittersweet news for Estopinal.

“It validates everything I’ve been harping on for years,” he said. “This is a huge problem for us, because it makes it more challenging for us to keep levees and walls high enough to keep surge out.

“This landscape is always moving, and that means this job is never finished. We can’t rest on the datum (elevations measurement) we have when we start a project, because it’ll be out of date in five years.”

For most of coastal America, NOAA recalculates mean sea level once every 15 to 20. But Southeast Louisiana is on a five-year schedule because the Mississippi River deltas it rests on are sinking and crumbling at such a rapid rate.

Levees on the river built for flood protection and to aid shipping have blocked the annual spring floods that for eons slathered the delta with new layers of land-building sediment. Meanwhile, thousands of miles of canals dredged for oil and gas development have destroyed the delta’s hydrology by allowing an influx of vegetation-killing salt water deep into coastal marshes. Just under 2,000 square miles of the state’s coastal wetlands have been turned to open water since the 1930s, a loss that continues at the rate of 16 square miles per year.

Engineers say the constantly sinking and shifting landscape makes the area one of the most difficult to build on. The Army Corps of Engineers said it took account of subsidence rates while constructing its $14.5-billion post-Katrina storm surge protection system around the metro area. And the corps vows the system will meet design specs as it is turned over to the local sponsor – the authority Estopinal sits on. But in the past 18 months the corps has been forced to raise at least two sections at a cost of millions because the sinking happened faster than it forecast.

That unpleasant surprise has confirmed the urgency of Estopinal’s calls for more frequent reevaluation of the system’s subsidence-prone underpinnings.

“They haven’t redone the datum for this system since it was started — and that was eight cotton-picking years ago,” he said. “You might start out with something that’s accurate, but the way this land moves, you’re not going to be accurate a few years later. This latest data from NOAA just validates my concerns. There’s a reason they’re redoing southeast Louisiana every five years — not 10 or 15 or 20.

“And there’s just too much at risk here to assume anything. This place moves too much and too fast.”

NOAA will update the Flood Protection Authority on these latest findings at a meeting of the agency’s Operations Committee meeting, 9:30 a.m. Thursday , in the Orleans Levee District’s lakefront headquarters, 6920 Franklin Ave.