If you thought sinking land and rising seas were the only things we had to worry about in south Louisiana, think again.

Tsunamis have now joined the list.

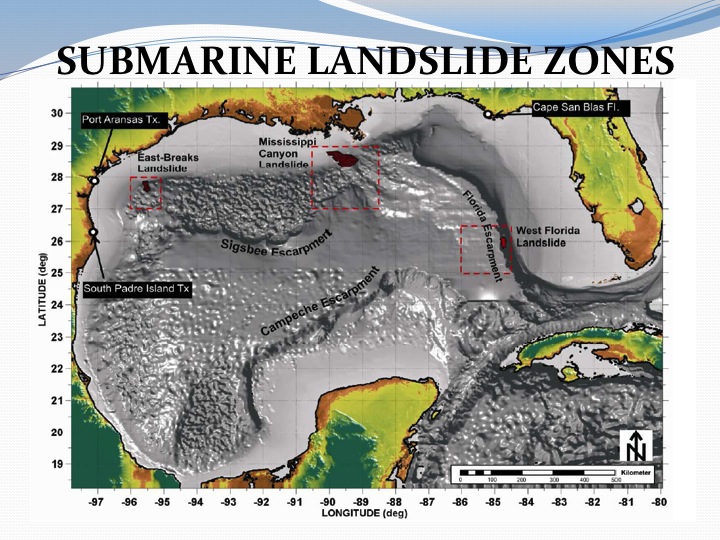

Researchers with the National Weather Service say a 15-foot wall of water could roll across Grand Isle if a landslide occurred in the Mississippi Canyon, a trench in the Gulf of Mexico floor about 30 miles off the mouth of the Mississippi River.

And unlike a hurricane, residents would have just an hour’s notice, not days.

Such landslides have happened about once every 1,000 years in that area – and that time frame is almost up.

“It should be stressed that it is a low probability event — one in a thousand — but it still is a credible event, and would be of a high impact,” said Joe Rua, the lead forecaster and Tsunami Program Manager for the Lake Charles office of the National Weather Service.

The National Weather Service directed its coastal offices to investigate tsunami possibilities after the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami. Rua said his team found evidence of previous slides in the canyon, which could cause significant tsunamis.

The hypothetical landslide used in National Weather Service computer model was 13 miles wide, 40 miles long and dumped enough rocks and sediment into the canyon to fill 38 Superdomes. The Gulf is more than 7,000 feet deep at the edge of the canyon, which is another 300 feet deep at the site in the model.

“Basically, the material falling into the canyon would displace the water that is already there, and that would cause the wave,” Rua said. “It wouldn’t be very noticeable in the open Gulf, but as the wave reached the shallower water near the shore, it would rise up.

“We estimate it would be about 14 to 15 feet [high] at Grand Isle, 10.5 feet in St. Mary Parish, and about 4 feet in Cameron Parish.”

The height of the tsunami would drop quickly as it moved inshore, due to friction from the land. Rua said a 10.5-foot wave entering the Atchafalaya delta would only be 5 feet by the time it reached Morgan City.

“A hurricane’s storm surge doesn’t drop as quickly because the energy behind it — the storm — is moving with it,” Rua said. “The tsunami doesn’t have that. Once it hits land, it loses energy rapidly.”

The likely trigger of a future slide would be seismic activity, which has been rare in this area; the eruption of large gas bubbles through the sediment layers at the base of the area; or the sheer weight of the sediment resting on the edge of the canyon.

Rua said more modeling has to be done to fine-tune the results. The purpose of the exercise was to alert communities to tsunami risk so they could prepare for the possibility in case “this once-in-a-lifetime event occurs.”

“Basically, we will probably only have one chance to get it right, and there won’t be a do-over,” he said.