When my husband and I decided to move to New Orleans, we had one goal in mind: to work as little as possible.

Back in Chicago, I was always working, and my long office hours left my life lacking. I wanted out, but I didn’t know what else to do.

That’s when my husband and I found a community garden. Even though we were inexperienced, we brought home bundles of organic vegetables every week. We slashed our grocery and restaurant budgets, and began to see that our hobby could help us live more and work less. We just needed more space.

Cold, concrete Chicago didn’t offer us many options. Faced with short growing seasons and small lot sizes, we decided to look for a new place to call home. When we shifted our sights south, New Orleans was the first place to catch our eye.

We were drawn to the city’s independent culture — less a rejection of mainstream America than an affirmation of itself. And we were impressed by the city’s ability to rebuild in the wake of disaster. It seemed New Orleans had the right mix of ingenuity and collaboration to support a self-sustaining way of life.

But our cross-country leap of faith hinges on the economy. In order to work less, we need to find affordable housing and a place to grow our crops. While rising real estate prices have made it difficult for us to find the right spot, some signs give us hope that we’re headed in the right direction. Most often, they’re signs for community gardens.

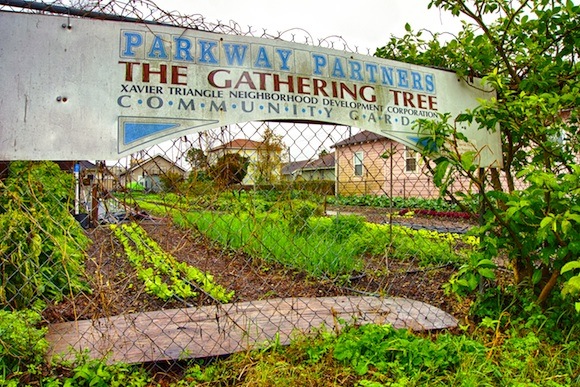

Whether large and officially funded or small and informal, these vacant-lots-turned-vegetable-patches dot the city. One local non-profit, Parkway Partners, is involved with 43 community gardens, urban farms and orchards in the New Orleans metro area, and there are plenty of smaller operations as well.

Community-farming projects are popular with nonprofits because they beautify neighborhoods, reduce food scarcity and increase collaboration. Plus, under the right management, they can create an economic engine where none existed before. They can put food on people’s plates — and then some.

I’ve spent enough stolen minutes trying to fatten someone else’s wallet. I came here to find a better way to use my time. I just hope I didn’t get here too late.

If garden surpluses are sold at farmers’ markets, to local restaurants or to food co-operatives, these projects can start to pay for services and even create jobs. And if low-cost local crops begin to filter through the system, fresh food will be cheaper for everyone. But to get this engine running, more people need to get involved.

That’s where organizations like the New Orleans Food and Farm Network come in. To help more communities shorten the food chain, the network has partnered with New York-based non-profit 596 Acres to build an online tool called Living Lots NOLA. This tool lists unused lots by zip code and outlines ways groups can obtain land, such as working out a deal with a private owner or getting government permission to plant on blighted lots.

The local food movement also got a jumpstart in November, when a new urban farm center, Growing Local NOLA, broke ground in Central City. The center will offer garden plots and agricultural classes, and create a source of local produce for grocery stores and restaurants.

But even as it seems that New Orleans is poised to become an urban farming hotspot, new zoning regulations have taken aim at residential gardeners’ rights. The new Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance (CZO) currently under review would make it costly or illegal to use a neighborhood’s natural resources to improve its economic position.

For instance, under the new CZO it would be illegal to own more than six chickens per residential lot. While this may seem reasonable for a homeowner with a coop in the backyard, the rules make less sense when applied to a lot that has become a communal farming space. The new regulations would also make it harder to sell eggs and produce harvested on residential land.

Advocates believe these rules, along with other changes to the CZO, will start to standardize neighborhoods and drive up property values. But it would also push New Orleans’ mixed-used spaces towards the cookie-cutter model that commercial investors prefer. And these big box stores have set their sights on this historically small-scale town.

As the fastest growing major U.S. city, New Orleans has become a target for large national retailers such as Costco, Walmart and Whole Foods, all of which are expanding local operations. And with Mayor Landrieu committed to helping smooth these companies’ access to the New Orleans market, it may not be long before New Orleans’ boulevards are indistinguishable from those in Atlanta or Detroit.

Big-box stores do bring jobs and investment, but their financial success is built on the backs of employees desperate enough to work for less than a living wage. It’s built on white-collar workers who are busy enough to believe convenience is king. It’s built on a society that’s ignorant enough to think what they’re selling is better, safer and cheaper than what we can make for ourselves.

It’s true that taking home a paycheck is often simpler than mastering all the skills required to actually make it through the day. The microwave, the drive-thru, the plastic-wrapped treat — they give time back to us. But what are we doing with it?

I’ve spent enough stolen minutes trying to fatten someone else’s wallet. I came here to find a better way to use my time. I just hope I didn’t get here too late.

Tegan Jones is a freelance writer and editor who specializes in business, environmental and nonprofit issues.