As she prepared to mark the anniversary of Hurricane Katrina, Kimberly James had finally found her way home, or so she thought.

Eight years after the hurricane upended her life, James, 47, had outlasted the misery of temporary relocation — first to Texas, then to a Baton Rouge shelter. She had prevailed, more or less, in skirmishes with her insurer, her mortgage company and New Orleans city bureaucrats. The Road Home program had finally coughed up $52,000, and she had a city building permit in hand to rehab her beloved family home on Pauline Street in the Upper 9th Ward.

This past January, a contractor set to work and James joyfully told her daughter that the house should be ready for her son to occupy as he began the fall semester at the University of New Orleans. New doors and windows, still bearing the trademark stickers, are clearly visible in the photograph that a city inspector shot on a visit to the property in March.

But on July 16, James’ world caved in with the suddenness of a floodwall undermined by surging stormwater. That day, the man she had hired to maintain her lawn notified her that her house had been bulldozed, without prior warning.

“We didn’t know the property was headed to demolition. We just thought that we had to maintain the property up to code, and we did that.”—Kimberly James

James tearfully described the shock of receiving the call. “I didn’t know what to do. I called the police and filed a report. I just didn’t know who to call.”

Adding insult to deep injury, the city sent her a bill to cover the cost of the demolition, which is its standard practice.*

There were as many post-Katrina housing struggles as there were people struggling to come home to New Orleans — people who couldn’t get a Road Home grant, people shortchanged by their insurance companies, people who got crosswise with city inspectors and regulations as they waited for a check. Sadly, Kimberly James’ experience was not unique.

Her home fell to the zealousness of the Landrieu administration’s commitment to eradicate 10,000 blighted structures, an instance of the government’s right hand not knowing what the left hand was doing.

Who gets the insurance money?

James, the divorced mother of three kids, was working for the U.S. Postal Service as Katrina approached the Gulf Coast. The day before landfall, they fled to Houston. By the end of September, they had ventured back to a shelter in Baton Rouge, and James began trying to put her life and her career back together.

The Postal Service offered her a job in Baton Rouge, and she and the two boys — Brandon, then 11, and Christopher, 5 — moved into a rented house with some 15 relatives. In January 2006 she sent her daughter, Ceisha James-Hayes, 17, back to Mount Carmel Academy in New Orleans to live with family friends and finish her senior year.

By July 2006, James and the boys had an apartment of their own and she was able to turn her thoughts to rebuilding the house at 2138 Pauline St., which had taken on 5 feet of water in Katrina’s aftermath.

The modest, three-bedroom bungalow, located across the street from William Frantz Elementary School, had a living room, den and jumbo-sized kitchen. It had a big yard, too, a carport and even a little shed with an extra bathroom. James and her husband bought the place in 1998 and, after the divorce, she had assumed full responsibility for the $675 monthly note.

The first skirmish in the family’s battle to return to New Orleans was with the mortgage company, General Motors Acceptance Corporation. James had collected $89,000 in flood insurance — enough, friends told her, to start renovating. To complete the work, she knew she’d need help from the state-managed Road Home program.

But here she ran into a Catch-22: Road Home initially told her that the insurance settlement was generous enough to disqualify her from receiving a grant. GMAC also had designs on the insurance money: It required that James use it to pay off her note, something that had stymied other homeowners as well.

“So there I was with clear title to the property but without the money to make it a home,” James recalled.

She concedes that the property fell into disrepair. Her night job in Baton Rouge and childcare responsibilities during the day left her with little time to run back and forth to New Orleans. In January 2011, the city cited the property for numerous code violations, including tall grass, unboarded windows and weatherboard deterioration.

Significantly, however, the house was never declared to be in “imminent danger of collapse,” a designation that allows the city to bypass various notification requirements and demolish the house immediately.

Road Home reconsiders

The citations came with a stiff lien against the house: $8,000, which James managed to get reduced to $800, and another $500 for lawn mowing — no matter that she had been paying a service to do yard work.

And if she didn’t fix up the property, the city threatened to tear the house down. Once she paid the fines, she thought the issue was resolved.*

Even with these burdens, James was squeaking by. With the Postal Service job, she had been able to make a downpayment on a small house in Baton Rouge. But New Orleans was where her heart was.

Finally, she caught a break. Road Home reconsidered her application and agreed in May 2012 that the Pauline Street house was eligible for the Blight Reduction Grant Adjustment program, initiated in the previous year. James would get $52,000.

“People told us to just give the house up, but how could we do that? That was all we had left. All the pictures, videos and memories were gone. The shell of a house was all we had.”—Ceisha James-Hayes

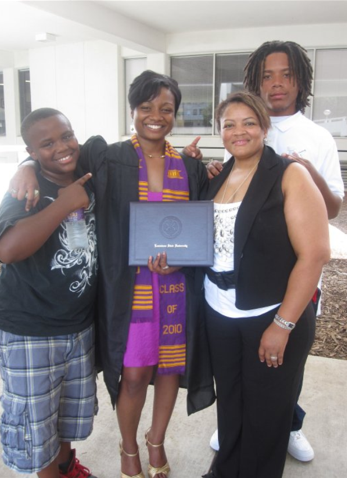

Her daughter, who graduated from Louisiana State University in 2010 with a journalism degree and now works for a computer company in Lafayette, remembers her mother crying for joy as she read the Road Home letter to her over the phone. “We can go home now. We get to go home!” James shouted.

“She immediately started calling contractors to get quotes,” James-Hayes said.

With the grant in hand, James glimpsed the possibility of finally putting Katrina in the rearview mirror. The family’s ordeal had been protracted, but — ever alert to a silver lining — she saw the timing as an opportunity for redemption. The house would be habitable again just in time for Brandon to live there as he transferred from LSU to UNO, reclaiming the hometown he so desperately missed.

“Brandon was never comfortable in Baton Rouge and always dreamed of coming back to New Orleans to live,” James said, holding back tears. “The house was something I could do to make it right for him.”

But what James didn’t know was that in June 2011, less than a year before the good news from Road Home, the city had asked the Neighborhood Conservation District Committee, which oversees historic parts of the city, for permission to demolish the Pauline Street house. It was part of the Landrieu administration’s “strategic demolition” program to deal with blighted properties.

The city secured a permit to tear down the house in November 2011.

James, who had driven down from Baton Rouge to attend a prior code enforcement hearing, said she never received notification of the hearing at which the city’s demolition request was considered.

According to city spokesman Tyler Gamble, the city’s Code Enforcement department does not send letters to property owners to inform them of such hearings. The Neighborhood Conservation District Committee, he said, “would have posted the notice of hearing on the building itself and the agenda would have been published in The Times-Picayune as the journal of record.”

However, city code says that when the city submits a demolition request to the Neighborhood Conservation District Committee, “no less than ten business days prior to the first hearing, a letter shall be sent to the property owner via regular or certified mail to the last known address verified by the tax assessor records.”

In October 2010, the Landrieu administration put blight remediation at the top of its to-do list, a goal that appears to have collided with James’ effort to renovate her property.

In announcing his plan to rid the city of 10,000 blighted properties, Mayor Mitch Landrieu said, “I’m putting you on notice now: Today is the day to start bringing your property into compliance.”

It’s a warning James-Hayes wishes government agencies would heed when it comes to helping people rebuild. “They should have the same timeline for the government programs in regards to helping people,” she said.

City issues permit to rebuild condemned house

In July 2012, two months after the Road Home grant was awarded, James hired contractor Kenneth Davis. He applied for a permit, and the city issued him one — on a building it had permitted for demolition eight months earlier.

Davis said he mistakenly thought the permit was good for 12 months, but Gamble said building permits are active for just six months. The permit expired in January 2013.

Davis continued his work. He said the interior work, rough framing, electrical and prep for drywall was completed by June. He expected his crew to finish the work this fall, in time for Brandon to start at UNO.

In March, Hillary Carrere, a demolition coordinator in the city’s Code Enforcement department, went by the property and took pictures. The new doors and windows — for which James had paid $2,500 — are clearly visible. The two pictures in city files are not accompanied by any sort of written report, Gamble said.

If the city was strict about enforcing the six-month building permit, it was rather more lenient on its own behalf. The demolition permit that James claims she never knew about had a one-year shelf life. Though it had been issued in November 2011, no one had acted on it.

But on June 18, without seeking reauthorization by the Neighborhood Conservation District Committee, Johnny Odom, chief building inspector in the Department of Safety and Permits, signed an extension until the end of August.

Within a month, the house was gone. The grounds for demolition, according to Gamble: a “significant lack of progress” in rehabbing the structure. Given that there is no written report, it is unclear how that judgment was rendered.

James is mystified by the city’s conclusion. She asked how the inspector could have determined that construction wasn’t progressing when most of the work was done on the interior, and the inspector couldn’t enter the house.

“We didn’t know the property was headed to demolition,” she said. “We just thought that we had to maintain the property up to code, and we did that.”

James-Hayes says she still holds out hope that the family will be able to rebuild. “We felt cheated for a long time because we feel like we are good people. We work hard; we pray hard, and it just wasn’t right that we were still struggling.

“People told us to just give the house up, but how could we do that? That was all we had left. All the pictures, videos and memories were gone. The shell of a house was all we had.”

Now that’s gone too. In its place, Hayes has a bill from the city for the demolition cost: $12,181.72.

*Clarification: This story has been clarified to note that Kimberly James knew her house could be demolished if she didn’t deal with code violations on the house, but she thought that those issues were resolved once she paid the fines. It also notes that the city’s standard practice is to bill for demolitions.