Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office employee Elizabeth Boyer has appeared frequently in the news, in court and in the City Council Chambers during the three-year funding dispute between Mayor Mitch Landrieu and Sheriff Marlin Gusman.

That’s because Boyer is better positioned than most to discuss the sheriff’s finances. As Gusman’s assistant comptroller, she’s one of his top administrative employees, an accounting manager responsible for preparing budgets and financial reports.

Her job description lays out a broad scope of work: “Responsible for all functions associated with the Accounting Department including budgets, financial statements, etc.”

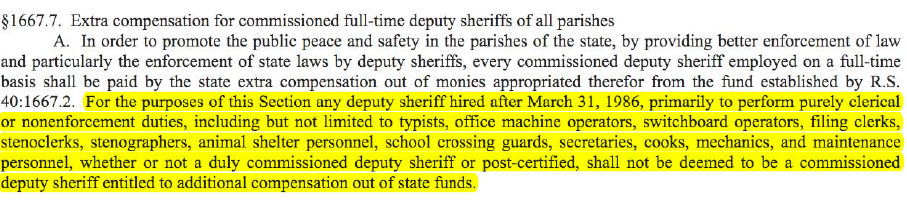

It does not mention anything about guarding inmates at the jail or conducting criminal investigations. Yet Boyer, along with dozens of others whose jobs appear to have little to do with law enforcement, is receiving as much as $500 from the state every month — $6,000 per year — money intended to supplement the often low pay for deputies whose primary responsibility is law enforcement.

All together, as much as $220,000 a year is being paid to Sheriff’s Office employees whose job descriptions appear to have little to do with law enforcement, The Lens has found.

Boyer’s annual salary is $69,000 before the supplement, compared to $27,000 for a deputy who would be eligible for the supplement after a year on the job. The Sheriff’s Office has referred to Boyer as its comptroller, rather than assistant comptroller, in the past, and the personnel report does not list anyone as comptroller in the Sheriff’s Office’s Finance Department.

A spokesman for Gusman said The Lens is not interpreting the law correctly and that all employees are being paid properly.

New documents provide more details

The Lens began investigating Gusman’s use of the extra pay two years ago after receiving a tip from former deputy and whistleblower Bryan Collins. Collins identified 51 employees he believed were receiving the pay despite being ineligible. Collins’ list included maintenance workers, medical staff and clerical workers. All those positions are explicitly excluded from supplemental-pay eligibility by state law, even if the employees are trained and commissioned deputies.

The Sheriff’s Office has denied the allegations, claiming in 2014 that many of the employees on the list were, in fact, doing law-enforcement work in spite of what their job titles suggested. That has been difficult to verify based on previously available information. But personnel reports prepared by the Sheriff’s Office last month provide the most thorough information to date on every employee’s actual job duties. As part of a federal consent decree to reform the city’s jail, Gusman submitted the reports to the city, the U.S. Justice Department and U.S. District Court Judge Lance Africk, who is presiding over the case.

The Lens obtained the documents — printed in minuscule type — through public-records requests to the city and Gusman.

Cross-referencing these with a report on the Sheriff’s Office’s use of the supplement pay submitted to the state last month, The Lens found at least 37 employees receiving the pay who may not be eligible.

Three others are listed as part-timers, though the extra pay is intended only for full-time employees. Eight more were not working at all, either suspended or on extended leave.

The Sheriff’s Office responded to to a series of specific questions from The Lens with only a vague statement. It’s unclear what the job statuses of these 48 people were on Feb. 4, when Gusman certified under oath that they were eligible for the pay.

The monthly payouts are clearly being reviewed by the Sheriff’s Office. It reported one partial and one full refund of January’s supplemental pay for two of the employees who were not working. Maj. Rochelle Lee, who is suspended according to the court-ordered report, missed two days in January. Deputy Terri Smith, who is on extended leave according to the report, did not work at all that month.

“At the end of the day, the most glaring and obvious ongoing offense is, again, the continued payment to the likes of Elizabeth Boyer and [Dishawn] Richard, the credit union manager, who are just so obviously disqualified,” Collins said after reviewing the findings.

“It’s just mind-boggling that it’s so clearly articulated in the law,” yet those employees continue to receive the supplement, he said.

Sheriff dodges questions, says everything is fine

The Lens provided the Sheriff’s Office its full findings along with a list of questions last week. But after several days, the Sheriff’s Office responded only with a brief written statement that did not specifically address any of them.

“The Lens is misinterpreting and misapplying the laws applicable to state supplemental pay. Our research reveals that OPSO is complying with those laws and acting in a manner consistent with how those laws have been interpreted and enforced in the past,” wrote Phil Stelly, Gusman’s spokesman.

Stelly did not respond to a request to elaborate on the statement.

The combined pay of all deputies who may be receiving the pay improperly comes to hundreds of thousands of dollars every year, potentially millions over the course of Gusman’s 11 years in office.

In early 2014, following the publication of The Lens’ first story based on the tip, Collins sent a letter requesting that the Louisiana Legislative Auditor and the state Office of Inspector General investigate the matter. Both agencies have declined to comment on Collins’ complaint or confirm whether an investigation is in the works.

A number of the workers Collins identified have since quit, retired or moved to jobs guarding inmates. Medical staff, some of whom still work inside the jail, stopped receiving the extra pay because they no longer work for the Sheriff’s Office. Gusman privatized medical service at the jail in 2014.

Likewise for kitchen workers, one of whom, Eartha Grant, was identified by Collins and in Gusman’s 2013 payroll records as a cook, another ineligible position. Gusman handed those duties over to food service giant Aramark Correctional Services, which uses inmate labor, the same year. According to the court-ordered personnel document, Grant now watches over inmates working in the kitchen. But most of the 37 employees The Lens flagged as suspicious were included in Collins’ original list.

Here’s the job description Gusman provided for Capt. Mary Goodwin, one of the employees identified in Collins’ list: “Performs duties associated with being an acting Procurement manager.” And this for Deputy Donald Carrere, also identified by Collins: “Performs administrative duties for the Facilities department, performs some electrical, plumbing and minor facilities work.” Deputy Shirley Berry, who was not on Collins’ list: “Provides administrative and clerical services to the Chief of Corrections.”

The descriptions have no apparent connection to law-enforcement work, but all three were reported to be receiving the extra pay as of Gusman’s most recent report to the state Department of Treasury.

State relies on sworn certification of sheriffs

As Stelly noted in 2014, the state, not the Sheriff’s Office, is ultimately responsible for certifying that deputies qualify. But it makes those decisions based on forms submitted by sheriffs that are certified under oath, said Michelle Millhollon, a Treasury Department spokeswoman, in a written statement.

“It is the responsibility of the Sheriff’s Office to correctly determine which deputies are eligible,” she said. “Sheriffs or their designees sign notarized forms swearing under oath that the information they submit is true and correct. Only the sheriff’s office would know the details on a deputy’s daily job duties.”

If a sheriff’s office disputes a decision from Treasury, a state board of review decides. But the board rarely meets. According to meeting notices posted on the state’s website, it has not met since October 2014. Millhollon said the board only meets as needed to rule on complaints or questions about a deputy’s eligibility. Millhollon declined to comment on whether the employees The Lens identified were eligible for the extra pay.

Moreover, the information Gusman provides to the state is vague. In 2014, after being alerted to the issue by The Lens’ reporting, the state Department of Treasury sent a notice to sheriffs across the state informing them that they must include a percent breakdown of job duties in the application forms. But as of January, when it submitted its most recent application, the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office is not following the directive. The only job description listed is “care, custody and control of inmates.”

“Care, custody and control. That is the purpose of corrections. It’s not necessarily a job description,” Collins said.

The new descriptions came out of a court hearing about a purported staffing shortage at the jail last month. At the hearing, one of the federally appointed monitors overseeing reforms reported routinely seeing ranking deputies working clerical jobs rather than guarding inmates, The Advocate reported.

“I think it’s really time to find out exactly what everybody’s doing,” Africk responded, according to the article. Africk ordered the Sheriff’s Office to submit personnel reports including a “description of duties as to every person employed by the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office.”

The city, which is also a party to the consent decree lawsuit, is responsible for funding the Sheriff’s Office. Mayor Mitch Landrieu and the City Council have repeatedly criticized Gusman for a lack of financial transparency as funding negotiations have dragged on in the case.

Landrieu spokesman Hayne Rainey issued a broad statement in response to a summary of The Lens’ findings on state pay.

“Public safety is our top priority, and effective management of the jail is a key component,” he wrote. “Ensuring that public funds are allocated properly is essential to proper management of the jail.”