BATON ROUGE, La. — These days, Henry Montgomery, 69, is known as the man of few words who works in a gym at the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola.

Josh Carter, 70, worked next to Montgomery for years, cleaning a prison gym after games, but he knows little about his friend. “He is an easygoing fellow,” Carter said. “But he never said anything about himself.”

His attorney from a half-century ago believes that’s an enduring sign of developmental delays. Montgomery was a “slow learner,” with an IQ in the low 70s, said Johnnie Jones, now 95. He still remembers the day in 1963 when Montgomery, then 17, was picked up for the murder of a deputy near Baton Rouge.

Though Angola holds more than 4,000 lifers, few inmates have served as long as Montgomery. He has been there nearly 50 years, with no hope of release since his appeal became final in 1970. On the other side of the prison, inmate carpenters make caskets for lifers like him.

Tuesday, Henry Montgomery will be propelled into the national spotlight when the U.S. Supreme Court hears his case, Montgomery v. Louisiana.

Justices will decide whether to offer hope of parole to prisoners automatically sentenced to life in prison for crimes they committed before they turned 18. The ruling will impact 271 prisoners like Montgomery in Louisiana and between 1,300 and 2,100 across the nation. (The range is so wide because most prison systems don’t track prisoners who were juveniles at the time of their offense and because some prisoners have been recently released in individual court decisions that are difficult to track.)

The U.S. Supreme Court took up Montgomery’s case to resolve differing state interpretations of its landmark 2012 ruling, Miller v. Alabama, which banned automatic life-without-parole sentences for youth.

“Mandatory life without parole for a juvenile,” the justices wrote, “precludes consideration of his chronological age and its hallmark features — among them, immaturity, impetuosity, and failure to appreciate risks and consequences.”

Citing Eighth Amendment prohibitions on excessive punishment, the justices struck down laws mandating life sentences without parole for juveniles in 28 states and in the federal court system.

12 statesHave decided to apply the Miller ruling retroactively7 statesHave decided not to

In some states, the ruling cleared the way for some prisoners with life sentences to be freed. But states disagreed on whether the ruling applied to prisoners who had already received mandatory life sentences as juveniles.

Courts in 12 states have applied the Miller ruling retroactively: Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Massachusetts, Mississippi, Nebraska, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Texas and Wyoming. Courts have ruled otherwise in seven states: Alabama, Colorado, Louisiana, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana and Pennsylvania.

A few states have dealt with it legislatively, passing laws offering parole review after defendants have served a certain number of years, ranging from 25 years in North Carolina and Washington to 35 in Delaware.

The U.S. Department of Justice instructed federal prisons to identify prisoners affected by the Miller ruling. It has weighed in on Montgomery, saying the decision should be retroactive.

In Louisiana, Montgomery appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court after the state supreme court shot down his plea for resentencing.

The argument for Montgomery: Young criminals can change

The U.S. Supreme Court is not concerned with Montgomery’s guilt or innocence. Rather, his lawyers are asking the court to resolve his “unconstitutional confinement.” Because of the Miller decision, they argue, Montgomery and others convicted of murder as juveniles were imprisoned under a now-unconstitutional legal structure — one that didn’t take their youth into consideration and mandated an automatic sentence of life without the possibility of parole.

Among those arguing against retroactivity is the state of Louisiana, which contends that its prosecutors would have to reconstruct hopelessly old cases, like the one against Montgomery in the 1963 shooting death of Charles Hurt, a sheriff’s deputy.

In his case, the state argues that the court would have to determine “whether Montgomery’s youth should have impacted the sentence he received for a crime he committed a half-century ago … in a case where, as far as counsel can tell, virtually everyone involved … is dead.”

”If the court opens the door on this, when is any case ever finalized?”—East Baton Rouge Parish District Attorney Hillar Moore III

East Baton Rouge Parish District Attorney Hillar Moore III, one of the authors of the state’s argument, believes the case against retroactivity is strong. “If the court opens the door on this, when is any case ever finalized?” he asked.

The state’s contention is supported by Hurt’s daughter, Becky Wilson, who filed a brief along with the National Organization of Victims of Juvenile Murderers. Wilson was 9 years old in November 1963, when her father was fatally shot in a park near Baton Rouge. Making Miller retroactive would “deprive surviving family members of the finality that they have had for years,” Wilson and her group wrote.

Several groups and experts arguing for or against Montgomery have filed briefs with the Supreme Court documenting stories like his. They describe youths who committed murders in circumstances both grisly and appalling. Yet, over and over, petitions filed on behalf of Montgomery argue that the people who committed these crimes have changed and are now worthy of one specific form of mercy: a parole hearing.

One group of unlikely allies from Louisiana submitted an amicus brief. Pascal Calogero, a former state supreme court chief justice, wrote a joint petition with criminologist Burk Foster, former Angola warden John Whitley and the Louisiana Center for Children’s Rights.

Despite disparate experiences, the four parties shared a common understanding, they wrote: “They all have observed juvenile offenders, convicted even of the most serious crimes, processed through one of the most historically difficult systems of justice, and housed under the most violent, hostile, and hopeless conditions, who can and do find the spark of rehabilitation, and who can and do grow and develop to the point where they could be welcomed back into society.”

The Miller decision is premised on a similar sentiment, that life without parole was “at odds with a child’s capacity for change.”

As a young prisoner, Montgomery made choices that can be seen in the man he is today, said Calvin Duncan, a former Angola inmate who was held for 28 years for a crime he didn’t commit and lived in the same dorm as Montgomery at one point. “He was no trouble,” said Duncan, who doesn’t remember Montgomery ever getting a disciplinary write-up.

Some juvenile offenders “can and do find the spark of rehabilitation, and … can and do grow and develop to the point where they could be welcomed back into society.”—Joint brief filed on behalf of Montgomery

After observing Montgomery, Duncan concluded that he was “impressive.” After all, by the time Duncan made it to Angola in the late 1980s, Montgomery’s chances at an appeal had been dead for nearly two decades. “The law said that he was going to die in prison,” Duncan said. “Despite that, he did positive things, helping to coach the young guys, and working at the gym.”

Angola officials don’t allow reporters to talk with prisoners about cases, but Montgomery’s cousin, Diane Coleman, approached him on behalf of the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange during a recent visit. He told her that he had been advised by his attorneys not to comment.

He might not have said much anyway, said his aunt Janie Smith, 88, who typically visits him once a month with Coleman, her daughter. Yet Coleman and the rest of her family don’t equate Montgomery’s taciturn nature with a lack of intelligence because he comes from a long line of understated people.

Smith remembers him as a mild-mannered teenager who was raised by her parents until his arrest. She hates to see him in Angola, and she hopes that the Supreme Court hearing could lead to his release. “I keep praying for him,” she said. “I pray that God will open a door for him.”

Coleman, who is now 60, started visiting him almost 40 years ago. Before that, no one in the family was able to, she said. Their grandparents, who raised Montgomery, were elderly. His mother was autistic and unable to visit him on her own, she said. “They basically swept him under the rug.”

Though Angola’s rules allowed visits only from immediate family, Coleman was allowed to begin seeing him close to 10 years after he’d arrived, after prison officials looked through their records and found that no one else had come.

Coleman said her cousin has always been generous with his advice. Over the years, he has become a hero of sorts to her, she said. “Despite all that he’s been through, he is always cheerful and smiling.”

A shooting, and a roundup

Coleman was in grade school when her cousin, whom she calls by his last name, was arrested. She’s heard about that day all her life. First, deputies came to the house and roughed up her uncle, Wendell Smith.

“They beat him right in the presence of my grandmother,” she said. “The next thing that the family knew, they were getting Montgomery.” Like school friends who grew up with him, she also occasionally refers to him by his nickname, Wolf Man, given to him because of his oversized incisors.

Hurt had been killed in a park the day before Montgomery was arrested. His lawyers consistently argued that Montgomery, who was skipping school that day, became terrified and killed Hurt as the deputy frisked him.

Others aren’t sure he did it. After all, it was the early 1960s and police were often heavy-handed in working-class, African-American communities. Before it was annexed by Baton Rouge 40 years ago, Scotlandville, where the murder took place, was the largest majority-black town in Louisiana, a place where boys grew up hearing stories of innocent men who were picked up for random crimes and sent to prison.

To neighbors, a guy like Montgomery, who had known cognitive impairments, seemed like an easy scapegoat, someone who might be prone to confess.

Stories from that day don’t shed any light on Hurt’s shooting in the park, but they do help to place the crime in the context of the time.

One of the tragic ironies of the case is that, according to his daughter’s brief, Hurt had been assigned to Scotlandville because he was considered racially fair-minded. As his daughter wrote, “Hurt was different … because the Louisiana of the 1960s did not generally think that way.” He chose to work with the juvenile division and started a Junior Deputy program for boys from Scotlandville.

As a result, Hurt was familiar with the part of Scotlandville where he was killed. Outside the park’s entrance, some of the roads meander and feel almost rural. Many of the streets are named for birds — Cardinal, Grebe, Osprey, Cormorant, Sparrow, Goose. Its narrow streets are lined with large trees and modest homes, dotted with a few churches, auto shops, a liquor store and an American Legion hall.

Yet the area felt like a war zone the day Hurt was killed. Nearly 300 deputies and police officers from neighboring parishes came to set up roadblocks and make mass arrests. Black men and teens were detained all across Scotlandville that afternoon.

Seven of the arrested men located by the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange remember that day clearly, even 52 years later.

“Long as you were black, they were picking you up,” said Louis Walker, now 70, then a recent high school graduate who was arrested as he walked out his door on his way to look for work. That matches with the memory of Joe Louis Bowie, now 73. He was getting off the bus from New Orleans when deputies nabbed him. “Young, old, crippled, crazy, they were picking them up,” he said.

A Baton Rouge Morning Advocate story described the wide-ranging search. “Every Negro fitting the general description of the suspect, thought to be tall and slender, was apprehended.” Though bloodhounds were brought in, they didn’t pick up a scent, the newspaper reported.

In 1963, Isaiah Henry, then a 29-year-old military veteran, was arrested as he and five classmates drove home from Southern University, which sits on a curve of the Mississippi River across the railroad tracks from the park.

“What I saw: a lot of white officers and a lot of black people being questioned,” said Henry, now a retired math teacher. He recalled that he and his fellow students called Ulysses S. Jones, the university’s now-legendary dean, who came down to headquarters, talked to the sheriff and got them released.

There was no outrage about the roundup, Henry said. “I guess at that time it was just a part of life.”

Even today, if Morris Scott, 78, sees flashing lights and police cars lined up, he will not stop to ask what happened.

“Long as you were black, they were picking you up.”—Louis Walker, one of the many men in Scotlandville in roundup

The day Hurt was killed, Scott was headed to work not far from his house on Oriole Street. He always walked past a cab stand on Scotland Avenue, where he’d often stop to jaw with his friend, a cabbie. That day, they heard all sorts of sirens a few blocks away. Scott hopped into his friend’s taxi for a three-block drive to Anna T. Jordan Park, the scene of the crime.

A sheriff’s deputy had just been killed, a neighbor told Scott as several dozen people watched a crowd of white police officers search bushes and high weeds in the park. Then the officers moved toward the park entrance and trained their guns on the crowd, fingers on the triggers, Scott said. “They said, ‘Don’t nobody move.’”

It was the biggest manhunt ever seen in Scotlandville, said Scott and the other men, now elderly. The jail log for that day includes the handwritten names, ages and addresses of 60 men from 12 to 59 years old. In the column where a suspect’s crime was typically recorded, deputies simply wrote “investigation.” The Morning Advocate reported that the men were “booked for investigation and jailed,” then fed peanut butter, jelly and ham sandwiches for supper, and kept overnight.

Scott was taken to the sheriff’s office in a paddy wagon with 30 people. “We were sitting three high, one on top of each other,” he said, estimating that the police rounded up a few hundred people that day. Henry too thought the actual numbers were much higher than 60. He asked to hear all the names on the jail list, then said that of his group of six men, his was the only name recorded.

While most were released early the next morning, some were kept longer. Clyde Robvais, who was 16 at the time, is listed in the jail log as a “material witness.” Though he didn’t know about that notation at the time, the deputies’ perceptions became obvious: For the next 10 days, he was kept in jail and repeatedly asked if he’d witnessed anything. After he didn’t show up for his after-school dishwashing job, he was fired, he said, though he quickly landed another position.

Consequences were more weighty for Wilbert Forrest, 23, then a Southern University student, who was taken into custody the same day as Montgomery. Deputies told him that he looked like someone who had shot a policeman, he said. He was held more than two weeks, though he was transferred after about a week to neighboring Port Allen on a trumped-up charge — shooting at cows, he said — that was eventually dropped.

Forrest was forced to withdraw from classes because he’d missed too much time. “I lost that semester,” he said.

Emmanuel Cannon, who was 18, was walking home to lunch from Scotlandville High School when deputies stopped him. They walked him to Jordan Street, where they searched his family’s house, then handcuffed him and put him on the ground, he said. He spent the night in jail; his parents came to get him in the morning.

Soon afterward, he heard that his schoolmate, Montgomery, had been arrested. That never made sense to him.

“Later on in life, it hit me,” Cannon said. “That could’ve been me. They could’ve locked me up in jail for the rest of my life.”

‘Wolf Man’ goes on trial

The larger context — the racially segregated world that Montgomery lived in, along with his limited intellect and tough childhood — can’t be separated from his legal case, said Marsha Levick of the Juvenile Law Center, who is acting as co-counsel for Montgomery before the Supreme Court.

That’s the entire premise of Miller ruling, she said. Since the decision, no juvenile can face life in prison without parole unless a judge holds a hearing to examine how his youth and individual circumstances may have affected his actions.

“Context is important,” Levick said. “Montgomery’s case illustrates the type of miscarriage of justice that the court wanted to avoid in issuing its Miller decision.”

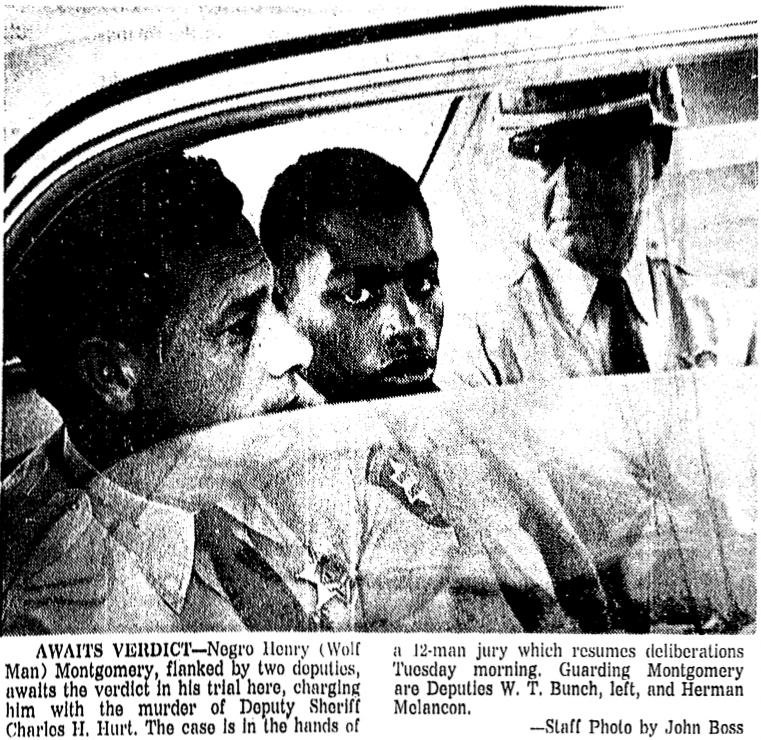

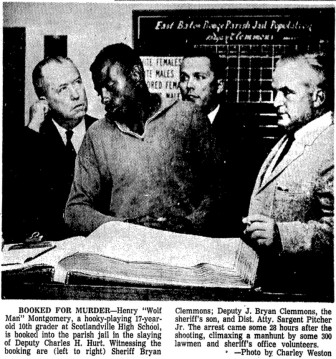

The day Montgomery was arrested, detectives took a newspaper photographer from the Morning Advocate along with them as Montgomery showed them the shed behind his grandparents’ house and pointed to the small .22-caliber pistol he’d hidden in the rafters. Montgomery also took detectives to the park and re-enacted the crime, the newspaper reported.

That same day, the detectives taped his confession. No need to inform him of his “right to remain silent” beforehand, because the U.S. Supreme Court’s Miranda decision wouldn’t be rendered for three more years.

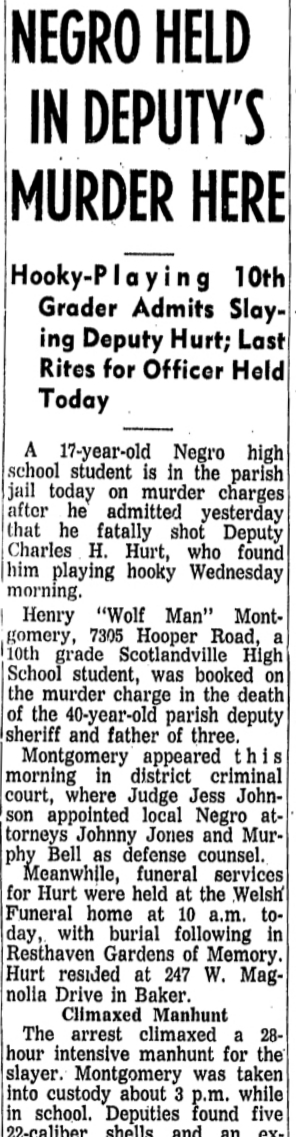

The following day, the headline in the Morning Advocate read, “Negro admits panic slaying of BR deputy: revolver and cartridges are recovered.”

The same day, the newspaper reported that Montgomery told detectives he had skipped out of his 10th-grade classes to take a nap in the park. There, he ran into Hurt, who had walked behind the recreation center to “break up ‘hooky-playing’ in the area,” according to the newspaper.

Johnnie Jones, Montgomery’s former lawyer, remembered what he’d heard. Hurt was patting down Montgomery from the waist down in case he had a knife or gun. But Montgomery had put his gun in the breast pocket of his jacket, Jones said.

“So while the police was patting him down from his waist to his shoe top, Henry had a Saturday night special, a little gun, under his arm,” Jones said. “He panicked and shot the officer.”

The landmark Gideon U.S. Supreme Court decision had come down eight months earlier, finding that defendants have a fundamental right to counsel. So the judge appointed two lawyers for the 17-year-old: Jones and Murphy Bell. They defended him for the next six years, through two trials, after a higher court overturned the first verdict.

Both attorneys were well-known for their civil rights work, defending activists in sit-ins and other protests and desegregating schools, parks and even amusement parks. In 1953, Jones was 15 days out of law school when he had agreed to defend those involved in the successful Baton Rouge bus boycott, which became a model for the Montgomery boycott three years later.

The two lawyers were devoted to the case even though they were unpaid; the court didn’t yet pay appointed lawyers, Jones said.

“If you bring in anything but a capital verdict, you’ll be jeopardizing the life of every law enforcement officer in this parish.”—District Attorney Sargent Pitcher, in closing arguments for first trial

The Morning Advocate covered the first trial extensively. Right from the start, his lawyers entered a plea of innocent by reason of insanity and called attention to his developmental disabilities. They described his “low mentality” and “weak-mindedness” and implied that he was paranoid and easily provoked. They argued that press accounts using his Wolf Man nickname had prejudiced jurors into thinking that Montgomery was a “character with a vicious nature.”

Yet his attorneys never said he didn’t murder Hurt. From that perspective, prosecutors appeared to have an airtight case. The audio of his confession was played for the jury, who also visited the park and the shed where Montgomery said he hid the gun.

In arguments that mirror some of the defenses of vulnerable youth made four decades later in the Miller case, Jones argued that Montgomery’s intellectual deficits — “the mentality of a three-year-old” — made it difficult to prove intent to kill. In other words, Montgomery may have killed Hurt, but it was a rash act, a mistake.

Still, District Attorney Sargent Pitcher was resolute in his closing arguments in the first trial. “If you bring in anything but a capital verdict, you’ll be jeopardizing the life of every law enforcement officer in this parish,” he told the jurors. They ultimately agreed with him.

After a nine-day trial — unusually long for a black defendant during that era — 12 white male jurors deliberated for a day and a half. They came back with a guilty ruling and a death sentence.

Montgomery’s lawyers appealed the death sentence, citing a few dozen errors, including the lack of black jurors, a prosecutor who described the lawyers with racial epithets and other prejudicial factors outside the courtroom.

Two years later, the Louisiana Supreme Court ordered a new trial for Montgomery, partly based on Klan cross-burnings that had been threatened before the start of the trial and partly because the trial had begun on what the city had declared “Charles Hurt Day,” meant to raise money for the victim’s widow and his young children.

The atmosphere denied Montgomery a fair trial, the court wrote. “No one could reasonably say that the verdict and the sentence were lawfully obtained.”

The second trial received less publicity. By that time, five years after Montgomery had originally stepped into the courtroom, the mood seemed less heightened.

Montgomery’s lawyers fought, unsuccessfully, to bar his confession on the basis of the Miranda decision. The district attorney did not push the death penalty. The trial took only a day and a half; the jury deliberated for about 90 minutes and found Montgomery guilty of first-degree murder.

He was given a mandatory sentence of life without possibility of parole and sent to Angola.

Life sentences for youth aren’t uncommon in some counties

Even if the Supreme Court rules that Montgomery should have an opportunity for parole, the door will likely open slowly, if at all. A judge with jurisdiction over his case could change his sentence or set him free. Or the state Legislature could grant parole hearings for prisoners like him after a certain amount of time served.

At each point, Montgomery could be released. Or not.

1,300-2,100Prisoners in the U.S. could get parole hearings271Prisoners in Louisiana could get hearings

For youths convicted of murder since 2012, life sentences are still possible, though they can no longer be mandatory. As a result, the Supreme Court justices wrote in Miller, the sentences would likely be “uncommon.”

That’s true — in most jurisdictions. Recently, the Phillips Black Project, named for a nonprofit law firm, published a study showing that nine states are historically responsible for imposing 80 percent of juvenile life-without-parole sentences: California, Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Michigan, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina and Pennsylvania.

That has continued despite the Miller decision. Over the past three years, the report found, a handful of counties — including Orleans and East Baton Rouge in Louisiana — have been responsible for a share of such sentences “widely disproportionate from their population.”

Moore, the district attorney for East Baton Rouge Parish, stands behind the decision to pursue life-without-parole sentences for juveniles in his parish. Since the Miller decision, four juveniles convicted of murder have faced such sentences, he said. “In three of four cases, the court found that life was appropriate,” he said.

Moore is familiar with research showing the brain is still developing well into adulthood. “I’m all for keeping kids out of the system,” he said, noting that he scrutinizes each case individually to decide whether young defendants should be kept in juvenile court or tried as adults.

“None of these cases are easy,” Moore said. “But some wave their hands and say, ‘You must try me as an adult.’ ” And in those cases, Moore said, he will continue to pursue life sentences if he believes it’s best for public safety.

Because of Miller, sentencing is now a two-step process: Juveniles who face life-without-parole sentences must have a sentencing hearing that puts their youth into context by examining brain development, history of hardships and home life. Similar hearings have been commonplace in death penalty cases since the 1970s.

Nothing like that existed in 1964 when Montgomery first faced trial. Yet, in their closing arguments, his lawyers presented similar justifications to explain, for instance, their client’s confession.

“What else could you expect that child to say, with the type of mind he has?” Jones asked. “From his very birth, this child has been ‘off.’”

Sure, Montgomery was 6 feet tall and — as press accounts had noted — he had even worn a “slight mustache” at times, Jones said.

“He looked like a man,” Jones told jurors, but his intellectual capacity didn’t match his physical maturity. “The size doesn’t make the man. The mind makes the man.”

Then Bell began his final arguments. He, too, foreshadowed the Miller decision as he described how his client lacked an intent to kill. Instead, Montgomery’s reaction was impulsive, Bell argued. “He merely panicked. He was scared and he had a gun in his hand, so he fired.”

This story is the product of a collaboration between The Lens, the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, the only publication covering juvenile justice and related issues nationally on a daily basis; and the Center for Public Integrity, a nonprofit, independent investigative news outlet.