I was invited to speak at a recent meeting of independent scientists from the Water Institute of the Gulf in Baton Rouge. Brig. Gen. Duke DeLuca of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers also gave a presentation.

DeLuca’s insights should be a wake-up call for all Louisianans who think state officials have a clue about how to rescue our coast.

The gist of DeLuca’s evidence completely refutes the claim by the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority that the way to rebuild lost land along the coast is to “reconnect the river to the marsh” with large-scale river diversions.

“This isn’t your grandfather’s river,” DeLuca said memorably.

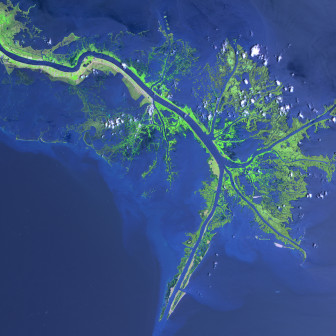

Louisiana is losing 16.5 square miles of land a year — roughly 10,000 acres — but more than half of this wetland loss is beyond reach of any diversion that might be created, no matter how big, DeLuca said. Moreover, as he pointed out, the Mighty Mississippi has nowhere near the land-building capacity it had 7,000 years ago when annual sedimentation created the delta that’s now rapidly disappearing. At the time, the river’s massive flow was fed by the meltdown of an equally massive glacier. No glaciers have been spotted in the Chicago area in recent years!

In arguing for diversions, the coastal restoration authority has made the Wax Lake Outlet over by Morgan City its poster child for the river’s land-building potential. But, as the general noted, even using 10 percent of the river’s total flow, since 1983 the outlet has been building only 250 acres a year.

To those of us who make our living harvesting seafood and guiding sportsmen through the waters we know, it seems like the coastal authority is so hooked on diversions that no amount of hard science will stop them.

Do the math: Even if we could utilize every drop of the river’s flow, we could only build 2,500 acres a year — just a quarter of what needs to be replaced just to break even. The problem, as DeLuca explained, is that the river carries only a quarter of the sediment it had prior to the 1950s, and only half of that sediment gets past Baton Rouge.

DeLuca also dispelled the widespread misconception that all the sediment goes out the mouth of the river and falls off the continental shelf. Not enough sediment makes it to the mouth of the river; that’s why there are no “mountains” of land at the crow’s foot delta. The mouth of the passes is the largest “diversion” in the world, yet some of the largest erosion rates occur there.

Faced with the Army Corps’ new findings, the coastal authority has come up with a new argument in support of a master plan that leans far too heavily on diversions. They now claim that the diversions will remove the harmful nutrients from the river — nitrogenous fertilizers, primarily — that cause the Dead Zone in the Gulf.

Say what? Rather than let the harmful nutrients go into the Gulf, we’re going to divert them into our precious marshes, the nursery for the planet’s most productive fishery?

Another view: David Muth, of the National Wildlife Federation, disputes Ricks’ argument and defends the state’s coastal master plan.Live chat Thursday: Join us at noon CST for a live, text-based Web chat with Ricks and Muth about how to rebuild the coast.

Anyone familiar with the freshwater diversion at Caernarvon, in St. Bernard Parish, will tell you that these same harmful nutrients have weakened wetland root systems. According to evidence from numerous scientists, including professor Eugene Turner of LSU, that process is prime suspect in the overnight loss of 47 square miles of land during Hurricane Katrina. Thirty-seven of those 47 square miles were in close proximity of the diversion near Lake Lery.

To those of us who make our living harvesting seafood and guiding sportsmen through the waters we know, it seems like the coastal authority is so hooked on diversions that no amount of hard science will stop it.

The authority just received a first installment of BP money — $67.8 million — and what did they do with it? Forty million — 60 percent of the total — was immediately appropriated for the engineering and design of the Myrtle Grove diversion, even though the fresh revelations by the Army Corps are sure to make the permitting process problematic.

Such a priority makes no sense. A far better use for $40 million would be to build land by funneling dredge spoil from the river bottom to the outboard side of the levees where it’s truly needed — a win for both deepwater shipping as well as the fishing industry. We need land NOW!

The corps predicts that in the early going — the first five to 10 years — diversions actually accelerate land loss. If my figures are correct, at the annual loss rate of 16.5 square miles a year, we could lose 165 square miles before a diversion builds even one.

I think it’s time we all woke up and abandoned the comforting fantasy that massive diversions will solve the enormously complex problems we face along the coast.

Charter boat captain George Ricks is president of the Save Louisiana Coalition, which advocates for wetland, environmental and coastal community interests.