With the French Quarter Festival marking its 30th anniversary and tourism in New Orleans verging on its highest levels ever, I thought it was a good time to remind residents and visitors that the beautiful and unique environment we celebrate today was very nearly sacrificed on the altar of supposed economic development more than four decades ago.

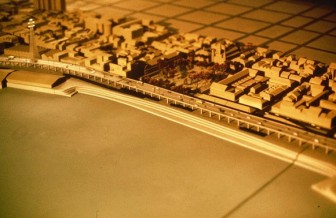

Without local people dedicated to preserving their local heritage, and the federal cavalry arriving just in time — in the form of Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, today there would be a multi-lane high-speed expressway between Jackson Square and the Mississippi River. The expressway was the vision of many city and state officials and some powerful local business interests in the 1950s and 1960s, and they very nearly succeeded in building it.

The expressway failed because of the determination of local preservationists, notably including William Borah and Richard Baumbach, who not only helped lead the fight against the road project but documented the controversy in their 1981 book The Second Battle of New Orleans: A History of the Vieux Carré Riverfront-Expressway Controversy. But preservation interests seemingly had lost the battle in the late 1960s as the project gained momentum and members of the state’s congressional delegation secured federal funding to ram it through.

In today’s America, too many forget that government is the creation of the people over centuries. There is a sound reason and a history behind federal regulations that were created, not by bureaucrats, but by elected representatives. In the case of the National Historic Preservation Act, local preservationists worked with the U.S. Conference of Mayors to “stop the federal bulldozer” — a rallying cry at the time.

In an era when Interstate highway construction and “urban renewal” were heedlessly ripping down unique historic properties and even whole districts, Section 106 was designed as a tool useful to local preservationists and as a way to force federal agencies to fulfill their missions without destroying irreplaceable remnants of American history.

The people who enjoy the French Quarter today are deeply indebted to Section 106, though many have never heard of it. But while New Orleans’ cultural heritage is unique, the way the French Quarter was saved is not.

Recently, to underscore this important point, the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation has launched a Section 106 Success Stories project that aims to present a handful of such successes to mark the 50th anniversary of the National Historic Preservation Act, in 2016. Case studies completed to date can be found at www.achp.gov/sec106_successes.html .

Of course not all the lessons of the Riverfront Expressway ended with the decision to spare the French Quarter. As the Treme neighborhood was to learn the hard way, one district’s victory could be another’s loss, particularly at a time when racial minorities were largely excluded from land use debates.

Today, there is good reason to rue the decision to put an expressway on girders above Claiborne Avenue, a development that was completed as the Riverfront Expressway was successfully defeated.* But the spirit of community preservation that now animates Treme took rise in the preservationist victory that spared the French Quarter. Whether that victory will be extended to include dismantling of the Claiborne overpass remains to be seen.

What would New Orleans be without the French Quarter? How would America be lessened by its loss? Ask that question with a different focus — any of the thousands of threatened places that have been saved thanks to Section 106 — and the importance of preserving America’s heritage becomes apparent.

*Clarification: The sentence was revised to make clear that the elevated Claiborne Avenue leg of Interstate 10 was not an alternative to putting an expressway along the riverfront. The two expressways were simultaneous proposals, one of which was defeated. April 30, 2013

Milford Wayne Donaldson, FAIA, was appointed chairman of the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation by President Barack Obama in 2010. He formerly was the State Historic Preservation Officer for California.