There was praise from most of the interested parties Tuesday when the federal Department of Commerce released the draft of its plan for spending what is expected to be more than $20 billion in fines stemming from BP’s Deepwater Horizon spill.

The RESTORE Act allows 80 percent of Clean Water Act fines resulting from the disaster to be used for ecosystem and economic restoration of the gulf. Current law would send the money straight to federal coffers for reallocation by Congress—with no guarantee it would be returned to the gulf.

But in the days preceding Tuesday’s happy announcement, a behind-the-scenes drama over a change in language on a website sent sparks flying between Capitol Hill, the Commerce Department and environmental groups, illustrating how jealously that giant sum will be guarded in the years ahead.

The controversy erupted as Sara Gonzalez-Rothi, senior policy analyst at the National Wildlife Federation, read the website of the Gulf Coast Ecosystem Restoration Council, which is charged with disbursing RESTORE Act funds under a formula established by the act. To Gonzalez-Rothi’s surprise, the Council stated that the 30 percent share of the total fund called “Pot 2”—as much as $6 billion from the $20 billion fine—would be used to “implement a comprehensive plan for ecosystem and economic recovery of the Gulf Coast.”

Economic recovery? This contradicted the letter as well as the spirit of the law which was passed after months of sometimes testy negotiations between politicians from the five gulf states, environmental groups and business interests. Pot 2, they had agreed, was to be used only for ecosystem restoration. Funding for economic restoration was to come from “Pot 1,” a 35 percent share of the fine – about $7 billion — that will go directly to each state.

Alarm bells went off, Gonzalez-Rothi said, because she had worked on the bill while serving as legislative council for environmental issues for Sen. Bill Nelson, D-Florida. She said economic interests pushing for a share of the fund to help boost businesses hurt by the spill accepted the final decision on getting direct disbursements from Pot 1.

“During the drafting and negotiations there was always this common understanding about what each pot could be used for,” she said. “One point being made during negotiations was that ecosystem restoration was an economic benefit because restoring those environments would help businesses impacted by the spill.”

“The gulf economy is so dependent on the ecosystem that an environmental disaster has economic consequences, she noted, adding, “If you can repair a pristine gulf ecosystem, you will in turn bolster the economy of the region for the long-term.

“The lobbyists for the chambers of commerce all sort of knew the allocation for this pot was only for ecosystem restoration. That’s why I was concerned to see this [on the website].”

Gonzalez-Rothi’s concerns were shared, not just by other green groups, but also by Louisiana officials. Since most of the spill’s damage to ecosystems occurred here, Louisiana stands to receive the lion’s share of Pot 2’s $6 billion, funds desperately needed to address the state’s ongoing coastal crisis.

Hopes that the website statement was just a typographical error crashed when Sen. Mary Landrieu, D-Louisiana, lead author of the legislation, met with acting-Secretary of Commerce Rebecca Blank. Blank told Landrieu the statement reflected her agency’s interpretation of the law. The senator took her case to the White House and later released this statement to The Lens:

The statute is very clear – the Comprehensive Plan, the mechanism for spending 30 percent of RESTORE funding, is exclusively for ecosystem restoration. So far, this administration has been a strong partner in advancing the RESTORE Act’s goals, particularly to mitigate environmental damage from the Deepwater Horizon spill.

The President’s September Executive Order reiterated that this is a “comprehensive plan for ecosystem restoration.” Anything to the contrary would upset the very delicate balance between environmental and economic development interests that enabled the RESTORE Act to become law. I will work with the administration to ensure that the final Comprehensive Plan is consistent with the statute.

Garret Graves, head of Louisiana’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority originally expressed little concern over the issue, telling The Lens by email:

While the drafting of the bill could lead to some confusion, a closer analysis clearly states that the 30 percent of RESTORE funds allocated to the council is exclusively for ecosystem restoration — not economic. The chair and ranking member of the U.S. Senate committee of jurisdiction share this position. All RESTORE Act funds that become available to the State of Louisiana will be limited to Master Plan projects.

Graves added: “I would rather focus on real problems rather than imaginary ones.”

Later however, he expressed thanks for having “some light” focused on the disparity and said the council was going to change the website language.

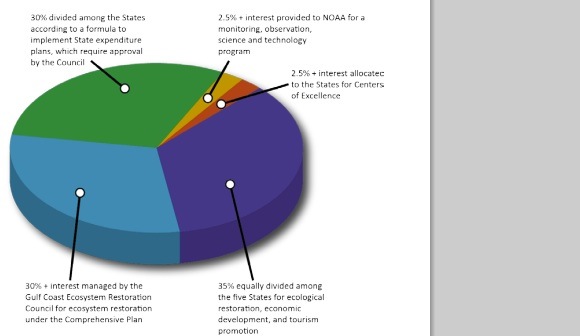

The issue was probably put to rest with release of the Council’s “Path Forward” document. A pie chart on the document’s second page states that a 30 percent slice will be applied to ecosystem restoration—with no mention of economic restoration.

That green groups didn’t consider this a minor kerfuffle is evident in the very first sentence of the joint press release issued Wednesday by the National Wildlife Federation, the National Audubon Society, the Environmental Defense Fund, the Ocean Conservancy and the Nature Conservancy: “The draft Path Forward released today is a welcome and encouraging first step as the Council clearly commits to directing 30 percent of the RESTORE Act funds to ecosystem restoration under the comprehensive plan.”

The announcement continued: “The Path Forward also outlines how the Council will ensure that economic investments in state expenditure plans will be consistent with its comprehensive plan to restore the Gulf’s natural resources.”

With a $20 billion pie on the table, it’s unlikely this will be the last squabble over RESTORE funding. Gonzalez-Rothi said the competing interests that drafted the bill will continue playing watchdog roles, including those for whom repairing the ecosystem seems less important than economic development.

“It’s not just the amount of money involved, there’s the issue of government accountability,” she said. “This will have attention on a national scale going forward because these are fines for violations of federal environmental statutes. There’s an interest on behalf of the national taxpayers who otherwise would have this coming back to the U.S. Treasury.

“So it will be watched very carefully by government accountability types as well.”