Ask Mayor Mitch Landrieu’s administration about its frequent failure to comply with public records law and it will tell you that it thinks it’s doing a good job – or, well, a better job than the previous administration under Ray Nagin.

Maybe so, but the letter of the law – which requires release of public records within three days of their being requested – is frequently violated. And the spirit of that same law – that public records are just that: public — is ignored altogether, many media outlets find.

Of seven records requests filed by The Lens, one request has gone unfulfilled for as long as eleven months, despite the city’s concession that it was a valid request. The unresponsive agencies include City Hall, the Orleans Parish Sheriff’s Office, and the New Orleans Police Department.

The law requires the city and other public bodies to hand over public records immediately if not in active use, and to provide them within three days of the original request if they are in active use. Any citizen may request a public record, though some – such as records dealing with sensitive personnel issues or litigation – can be withheld.

City officials have flatly denied The Lens access to three records:

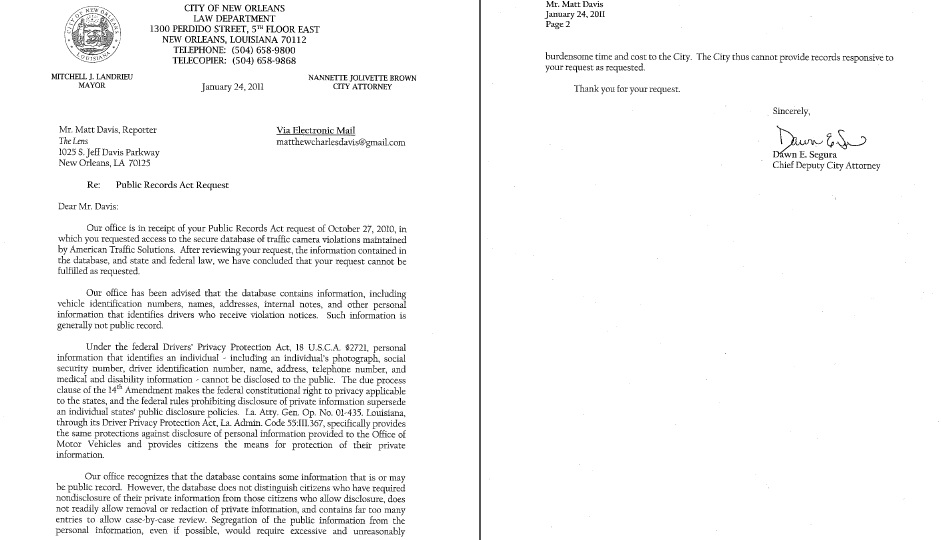

–The oldest is an Oct. 27, 2010, request for a database of red light traffic camera tickets. In denying the request, the city’s law department argued that giving the public a look at those records would violate the Federal Drivers Privacy Protection Act. The act forbids an official to hand out personal information on individual drivers, but the driving violations themselves – with the offenders’ names deleted – are exempted from the category of “personal information.” Further, the law expressly states that anyone requesting the information for research purposes is entitled to it. The city eventually conceded that while the violations themselves aren’t private, it would take too much time and effort to redact the private driver’s information from the public traffic tickets.

— On May 2, The Lens requested a photograph, taken by a citizen and submitted to police chief Ronal Serpas’ office, of an NOPD officer asleep in his patrol car on St. Charles Avenue. Officials said in a May 5 response that the photograph was part of a follow-up investigation, and was therefore not public. When the investigation was completed, on Aug. 31, and its conclusions – including the officer’s name — made public, the city continued to withhold the photograph, this time citing another law which forbids releasing photos of police officers to news media without the officer’s consent.

–A June 22 request for a draft copy of the NOPD’s “use of force” manual was ignored all summer. Last week, upon learning that The Lens was going public with this latest violation of the public records law, mayoral spokesman Ryan Berni finally responded to the request, but only to turn it down, the administration’s argument being that the manual made reference to “investigative techniques” that should not be made public.

In a flurry of belated compliance, the city also honored a Sept. 15 request for the past two years of grants made with money available to the city through the Edward Wisner Donation. This was faxed to The Lens on Sept. 22, the same day as Berni’s illegally belated response to the request for the manual. To have complied with the law, the Wisner Fund information should have been received by Sept. 18.

The city still has failed to respond at all to a June 22 request for records related to Police Chief Ronal Serpas’ study of the troubled paid detail system. To comply with the law, that request should have been honored on June 25.

On June 22, The Lens also requested presentations delivered to the Landrieu administration about the possible use of crime cameras to reduce the city’s murder rate. A city spokesman said in an email just Thursday that to the city’s knowledge, there is no record of these presentations.

Bill Quigley, a 30-year law veteran, director of the Gillis Long Poverty Law Center, and director of the Loyola Law Clinic, and a said in an email to The Lens that city delay of public records requests has historically been the norm:

“In my experience, the first response of governments is to deny or delay public records requests,” Quigley said. “When the lawyers get involved, they sometimes get it right but often the lawyers are told that the government does not want to release the information and the lawyers look for ways to deny making it public.” Quigley said attorneys with the city’s law department likely see themselves as working for the government, rather than the public.

In arguing that the administration has improved its game as regards public records, mayoral spokesman Ryan Berni said in an email Thursday that the city has received 461 records requests so far this year. He did not say how many have been fulfilled.

If Mitch continually says he is doing better than the guy who is considered the worst Mayor in New Orleans history then does that make Mitch the second worst Mayor New Orleans has ever had …. (?)

I certainly agree that public records requests must be fulfilled in accordance with the law and in a timely manner. Mitch does slightly better than past administrations.

That said the request for the database as outlined in your request is a bit burdensome but not in an insurmountable way.

the city can do one of two things to make this easy.

have the company run a query for *.everything except _privileged.field.name (or whatever) and export to excel.

or they can take the offline copy or shadow copy of the Database, export it and bring it back online as a different instance. From there they can just drop the tables containing the confidential information.

depending on the size of the database, either method will take a couple of days but no more.

The lens should check with their inhouse database guru and identify the database type (mssql, mysql, postgres, etc) and take that to your legal team to have it ready for a suit.